During the contentious effort that resulted in passage of the Atomic Energy Act of 1946, Sen Eugene D. Milliken (R-CO) played an important role in establishing an attempted US government monopoly over all atomic energy information.

During the House-Senate conference committee to resolve differences between versions of the bill passed by the two legislative bodies, Milliken gave a speech lasting 90 minutes that supported the highly restrictive Senate version of patent provisions.

Byron Miller, one of the people most responsible for writing the law and shepherding its passage described Milliken’s actions favorably.

After a careful study of the objections raised in the House, he concluded that the Senate section alonie could both preserve the secrecy sought by other sections of the bill and serve the public interest in a field developed entirely at taxpayers’ expense.

Miller, Byron S., “A Law is Passed: The Atomic Energy Act of 1946“, The University of Chicago Law Review, Summer 1948 Vol 14, Num 4. p. 816

Some called the patent provisions that Milliken defended “socialistic”. Others said they threatened the end of the American patent and free enterprise system. Milliken argued that the provisions were necessary to protect the interests of taxpayers by preventing private industry from profiting off of the technology.

Government ownership of all patentable information related to atomic energy helped discourage private investment and development. For eight years, the US invested only a tiny fraction of its vast atomic engineering and science budget in programs aimed at developing atomic energy as a future power source.

Without any support, it was impossible to design and build systems that could compete in the markets dominated by coal, oil and natural gas.

Until the patent section of AEA46 was revised by the Atomic Energy Act of 1954, no commercial enterprise made any investments in developing useful atomic energy.

Even though Milliken passionately defended patent provisions that had raised strenuous objections from groups ranging from the American Bar Association and the National Association of Manufacturers to the House Patent Committee, there no evidence of opponents accusing him of having special interest reasons for handicapping useful atomic energy.

Later on, in 1949, Millikin sought to maintain America’s policy of not sharing any atomic energy information with anyone, including Canada and the UK, its closest allies. The security barriers preventing information exchange extended past weapons-related information; they included industrially useful atomic information. At the time, both Canada and the UK were actively pursuing power reactor development.

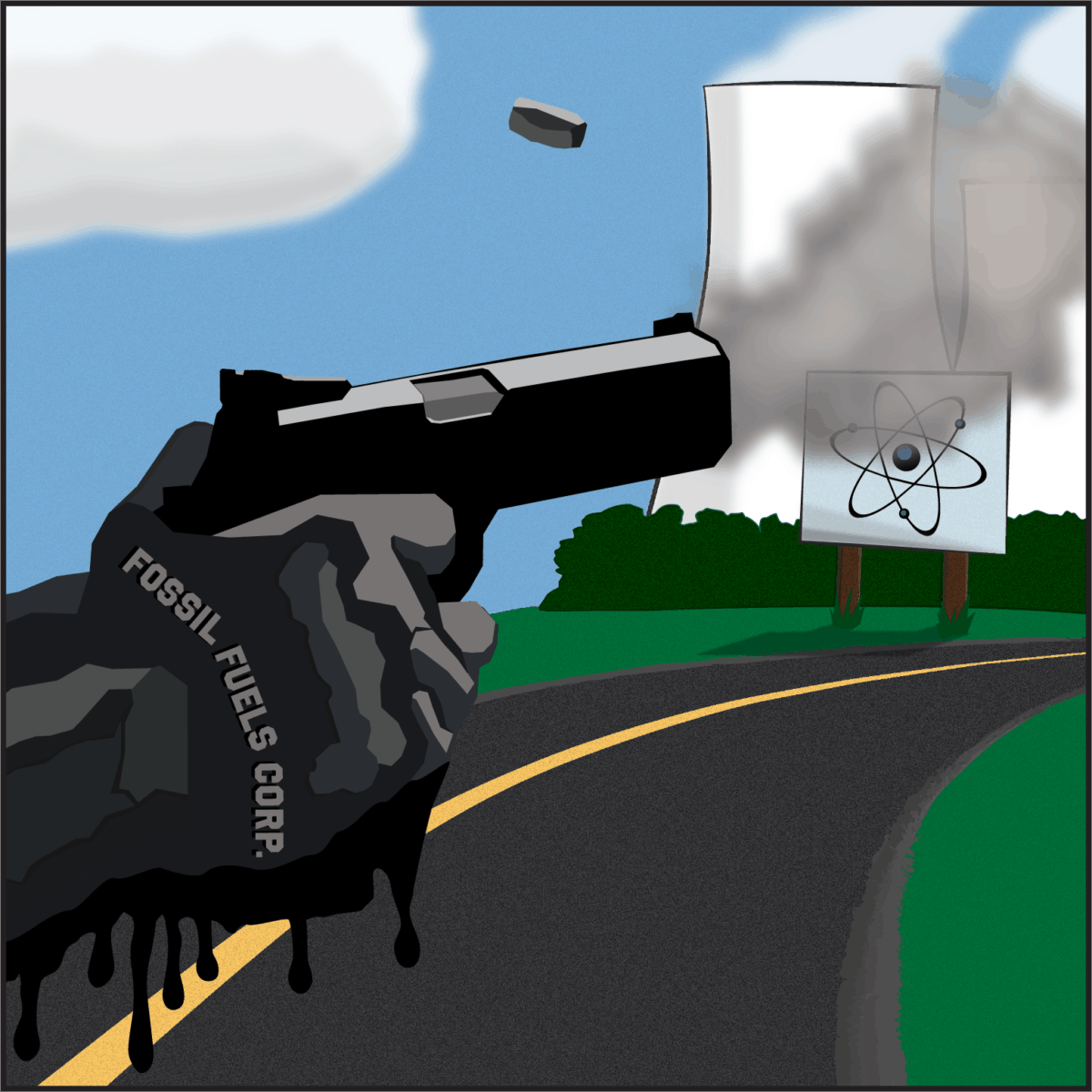

Looking back from our distant position in history, I’ve learned that Millikin had financial reasons to impede technological breakthroughs that might reduce demand for oil and gas.

Before his election to the Senate, Millikin had served as the president of Kinney-Coastal Oil. He was also part of an oil shale claims partnership that included Karl C. Schuyler, Sr. and George A. Taff. (Shell Oil Co. v. Kleppe, 426 F. Supp. 894 (D. Colo. 1977)

Those extensive leases were subjected to a number of challenges over several decades. Legal challenges were grounded that these claims did not constitute discoveries of a valuable mineral deposit pursuant to 30 U.S.C. § 22 et seq.

Challengers made the argument that shale deposits had no value because they could not be profitably extracted and marketed using available technology and existing market prices. (Shell Oil Co. v. Kleppe, 426 F. Supp. 894 (D. Colo. 1977)

As a Senator, Millikin supported a federal synthetic fuels program, which was aimed at producing useful liquid fuels from shale (kerogen) and coal. That program showed that oil shale had value because it could be mined and converted into useful liquid fuels.

There’s little doubt that Sen. Millikin understood energy’s important role in our industrial economy. Even though he was a self-proclaimed conservative, he advocated for governmental suppression of atomic energy development. He also supported federal programs that might make his own holdings in oil and gas leases more valuable.

Most historical interpretations of the political turmoil over atomic energy control during 1945-1946 focus on the topics of international control schemes, military versus civilian governance, and control of militarily useful atomic secrets. Few, if any, focus on the way that the resulting legislation and governance choices imposed an important delay in efforts to put atomic energy to use in serving humanity.

That’s my focus area.

While my research and broad-based reading on this topic will continue, I felt the need to stop and document a specific, intriguing story that qualifies as a smoking gun.

Note: On Atomic Insights, ‘smoking gun’ is a category of posts that document instances of nuclear opposition that can be directly tied to the desires of competitive industries to maintain their market share. It also applies to individuals whose wealth and power is directly tied to continuation of the Hydrocarbon Economy.

Considering that almost everybody at the time saw it – wrongly of course – as a military technology only, how do we know that wasn’t his motivation, too?

It’s not really unreasonable in context, either. After all, until 1949, we didn’t know that the Soviets already had everything they needed in terms of useful information, and the thinking was that keeping any information they weren’t already known to have out of their hands would at least slow them down. This would have been justification enough to keep the basic science classified until the Soviets could figure it out independently. I mean, you wouldn’t have been in favor of declassifying it during WWII, would you? Same logic.

@Stewart Peterson

There were many who saw atomic energy as a huge boon to mankind. They might have been in a minority, but silencing minority thought is not the normal path to success in America. The Power Pile Division at Clinton Engineer Works (a predecessor to Oak Ridge National Lab) was formed in 1945 under the guidance of Farrington Daniels. That group was well along the way of developing a useful power reactor demonstration that could be a stepping stone to rapid learning and improved designs.

It was the group that set up the nuclear power training program that Rickover and his small team attended. Almost immediately after the implementation of the Atomic Energy Act of 1946, that group was reorganized, relocated and eventually dispersed. Rickover took over their remaining assets and funding for a power reactor for submarines – a use that allowed a justifiable effort to close off access to industrially useful information.

My view from afar, supplemented by experience in the Navy nuclear program and many hours of reading history, is that the fossil fuel industry was ok with letting the government develop technology for useful power in a tightly controlled niche that did not do much to threaten their far larger markets.

Even such stalwart protectors of oil and gas interests as Speaker Sam Rayburn could get behind a secret nuclear submarine program without upsetting his Texas donors.

It’s completely normal in large organizations to silence people with unconventional ideas. Even in America, large organizations are large organizations. It doesn’t take a conspiracy to lack strategic vision and operational intelligence, be in a shrinking budget environment, and make “safe” decisions with committees instead of good decisions.

You are assuming that these organizations behave rationally – that there’s a motivated, logical answer instead of a dumb decision that somebody made on the basis of office politics. Frankly, I don’t know how a former Pentagon staff officer could conclude that. You’ve said yourself that you saw a massive amount of waste as a budget analyst, and surely, that waste wouldn’t have happened if the organization was behaving rationally.

You’re looking for a motive that doesn’t exist. The submarine service and the nuclear industry pride themselves on being competent and rational – but that doesn’t mean non-technical management and business side people are. It also doesn’t mean that nukes in management have the information they need to make rational decisions.

“Small, agile working group within government agency gets 90% of the way to solving problem X, then gets shut down and dispersed” is such a cliche that it shouldn’t surprise anyone when it happens, nor should anyone need to go to extreme lengths to explain it. It happens to a lot of people on a lot of projects. It’s happened to me. It doesn’t take a conspiracy, just the normal chaos and friction of a large organization with normal amounts of disorganization and office politics.

As a former Pentagon staff officer I worked with dozens of different organizations and projects. Even in large organizations, there are effective people and groups with vision and competence. They get things done. Their plans often get implemented exactly as conceived.

Sorry your experience has been different. It must be frustrating.

It is not frustrating, precisely because I know that’s what always happens to small, agile, highly-effective working groups with unconventional ideas. They’re paying me to be Sisyphus. I know what I’m getting into.

I can’t imagine that the DoD is any different. Sure, there are competent people within it – and, I have heard, there are also office politicians whose only deliverables are increasingly-abstract PowerPoint decks.

The people who focus on office politics tend to be the ones who succeed at it. Those who succeed at acquiring internal power are able to set the tone. The organization is thereby steered by them, and any large organization’s behavior is the net output of its internal power dynamics. This behavior must, therefore, not be rational, since social power is not derived from the merit of any ideas.

Not only is there no conspiracy here, there *can’t* be one. The internal dynamics of any large organization would immediately derail it – or any other attempt to have the organization follow a strategy.

Some of the people who successfully navigate office politics have many other skills and only devote enough of their talent to politics to get the job done. You have evidently worked most of your short career in dysfunctional organizations. I’ve seen examples of those, and sometimes even felt like they were in the majority, but I have also seen some dramatically successful organizations.

I’m also wondering why you are making these comments on a post that doesn’t allege any cooperation; it documents an instance where a particularly well-motivated individual used his elected office to convince others to take an action that placed huge developmental burdens on a potential competitor.

My story is designed to show how even a single individual can have the power to alter history. Read the link I provided that documents passage of the Atomic Energy Act of 1946 carefully. Recognize how many groups and individuals worked hard for a year to mold that act and how Millikin’s 90 minute speech pushed the final outcome in a direction that is unarguably damaging to technological development. It is impossible to successfully develop complex new technology in a tightly classified environment that has draconian rules preventing information exchange.

I was trying to address your reply to my first comment, which suggested that the AEC made a conscious, strategic decision to stop the initial power reactor program. I assert that it was unable to do so, as a result of its internal organization behavior. I also assert that conspiratorial thinking starts with the assumption that large groups of people can be rational, and proceeds to search for their motive. The reality? Most of the time they don’t have a motive. They’re drifting from one initiative to another, as one group or another gains internal influence.

Furthermore, as I was trying to say in the first comment, these classification restrictions made sense until 1949, given what we knew about where the Soviets were. We didn’t know, in 1946, that the Soviets already had the basic science to build an atomic bomb. Why declassify it until the Soviets had demonstrated that they had mastered it?

Given what we knew at the time, these restrictions on commercial development made sense. You don’t have to be an oil investor to think that.