Many observers of the nuclear industry will point to the disestablishment of the Atomic Energy Commission as one of the major turning points in the development of nuclear power as growing alternative energy source. For nearly 30 years from 1946-1974, the AEC was a focused agency responsible for all aspects of nuclear power research, development and regulation. After the Energy Reorganization Act of 1974, the research and development responsibilities have been reorganized several additional times while the regulatory responsibility has rested with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

Though the NRC is now considered to be one of the best places to work in the federal government, and though it has developed a strong staff with both technical and legal expertise, it has a legal mandate to only focus on preventing hazards associated with nuclear power and radiation. It is not allowed to balance the risk of insufficient energy or to acknowledge the likelihood that failure to build or operate a nuclear power plant will result in the construction or operation of potentially riskier forms of power like 1950s vintage “grandfathered” coal plants.

In a lengthy discussion with Drbuzzo on Depleted Cranium on a post about energy policy, we began talking about how this agency reorganization – which we both agree was focused on hindering the development of nuclear power – came about. You have to dig pretty deeply into the comments, but Drbuzzo became quite animated in his expression about the hurdles that the NRC placed in the way of building new nuclear plants.

Shannon:

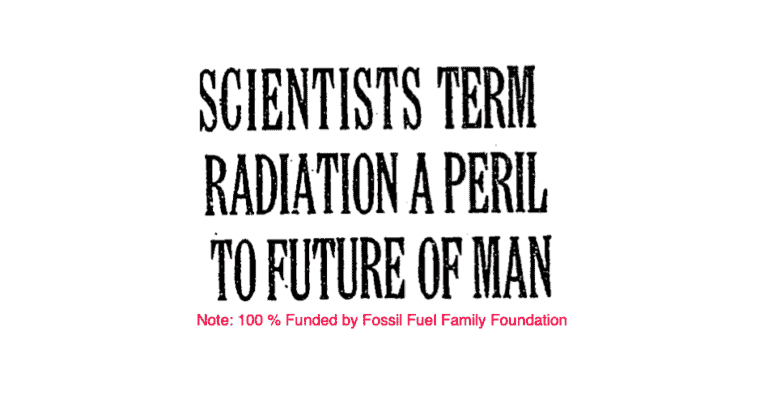

Just in case it has gotten lost in our give and take, the postulate that I am trying to advance is that people associated with fossil fuel and desiring to maintain its market share played at least as large a role in the slowdown of nuclear power development as “the leftists” that you blame.

You wrote:

For which you have zero evidence save for your dubious argument of economic motive. You don’t have public statement, confessions of people who regretted their actions, canceled checks, autobiographies, meeting notes etc. I on the other hand have all those things in abundance.

There are many books and articles on the subject of nuclear power development – I once spent a couple of years worth of free time perusing several aisles worth of such material in the US Naval Academy library. (Yes, I am a real bore in person.) Unfortunately, that period was before I owned a laptop and my notes are in random paper binders and hard to search or catalog. I also no longer have much free time available for library visits.

Fortunately, the world now has Google Books. I did some searching and found Congress and National Energy Policy by James Everett Katz, published by Transaction Publishers, 1984. That book includes details about the evolution from a focused Atomic Energy Commission with full responsibility for nuclear power development to our current situation. We now have a regulator with no responsibility for the risk of insufficient energy supplies or the risk of pollution caused by coal, oil and natural gas and a Department of Energy that has competing interests and budgetary priorities between all forms of energy.

Here is a quote from page 39-40 under the heading of

Atomic Energy: A Growing Problem

“The lack of a strategic approach to energy policy and distorted energy research and development priorities were among the elements that led to rising congressional displeasure about the heavy stress the federal government had given to atomic energy. Atomic energy – because of its dramatic quality and importance to national security – had from its inception received concentrated attention and support from the federal government.”

Later on page 40 the book continues:

“During the 1970s this independence was increasingly attacked, both from within the government and outside. During the 1973-1974 energy shortages criticism was augmented by supporters of competing energy sources and by public interest groups“

On page 51, after more details about the various interests and leadership in the effort to reorganize federal energy policy, the book goes on under the heading of

Curbing Nuclear Energy

Congress had led the White House into reorganizing the government’s energy research and development responsibilities by replacing the “anachronistic” AEC with a broad-based energy research agency. The new agency’s degree of commitment to nuclear power, as opposed to other energy sources was hotly contested, but the basic concept of reordering the structure met with little resistance…

Before ERDA could be properly established it had been necessary first to disarm the JCAE (Joint Committee on Atomic Energy), which had traditionally hampered reorganization efforts that might slow atomic energy development or diminish its fiefdom – the AEC. Partly because of congressional concerns about overemphasis on nuclear energy, the JCAE began to lose its once awesome influence…

Virulent public attacks had also weakened the JCAE, which was seen as being “outmoded,” forcing an “overconcentration,” and fostering “proprietary interest” in nuclear energy at the expense of other “more promising” sources of power…

Because much of the effort to overcome the nuclear lobby would have been wasted if it were allowed to dominate the newly formed ERDA, the Senate included safeguards to assure that all energy technologies would receive ample consideration. The Senate report of the ERDA bill sought “balance and meaningful priority-setting among the competing energy sources…

Finally, (for this comment, but certainly not the end of the evidence) page 54 provides a fairly clear summary of a couple of years of bureaucratic infighting and competing testimony.

ERDA (Energy Research and Development Agency) was an awkward conglomerate of competing interests in possession of a nebulous mandate and diffuse goals and faced with an antagonistic combination of clients…

Such eclecticism resulted from ERDA’s need to satisfy four constituencies. The atomic establishment wanted to push for nuclear energy development in every available format. Those generally interested in energy policy wanted a central mechanism that could rationalize and plan energy research, develop long-range objectives, and oversee the pursuit of these ends. Nuclear power opponents wanted a new nuclear safety agency split off from energy development because AEC could not realistically be expected to both promote nuclear energy and be circumspect about controlling, regulating and evaluating it. Finally, proponents of other energy forms – such as coal, solar, and oil – sought an institutional structure that would promote development of their favored energy form. To continue with only a pronuclear establishment, these three latter constituencies argued would result in an imbalance of government R&D efforts.

I am sure that those last three constituencies had a lot of meetings and discussions to hash out the final agreement that led to the passage of legislation that probably had more to do with the slowdown in nuclear power than any other – the Energy Reorgani

zation Act of 1974.

One of the major consequences of the disbanding of the JCAE, which Katz includes as part of reorganization effort, was to eliminate the congressional and senate staff expertise on the value of nuclear power for such applications as ship propulsion.

The US did not just stop building nuclear electric power stations, we also stopped building nuclear powered cruisers and destroyers and never did get around to building nuclear powered amphibious ships. We even decommissioned our few nuclear ships early rather than invest in the maintenance and upgrades of what were fairly unique designs without many following units.

We did build about ten carriers and continued building submarines. However all the rest of our naval vessels have been oil fired despite the proven tactical value of endurance and speed provided by nuclear power. Certain congressional committees and Navy budget submitters liked oil fired ships because they could be built for a somewhat lower initial cost.

The Navy liked getting more ships, even if they required refueling every few days. From the mid 1970s until just recently, it has been generally easy for Navy budgeters to convince Congress to provide operational funds for fuel each year and more difficult to educate them on the investment benefits of nuclear power. (BTW – please do not attempt to accuse me of ignorance on this particular issue.)

Interestingly enough, in the 1970s, the SINGLE largest customer for the oil industry in the US was the US Navy.