NRC’s imposition of Aircraft Impact rule played a major role in Vogtle project delays and VC Summer failure

Courtesy Southern Company

Projects that last as long as building nuclear reactors in the U.S. are analogous to extreme endurance competitions in which overall progress is the sum of all stages of the race. There is no magic reset button that allows recovery of time lost early in the race, even though the specific events that resulted in the lost time might have been forgotten by observers.

For the past dozen years, we have been repeatedly served stories bemoaning the growing costs and often delayed schedules associated with the Vogtle expansion project. At least the Vogtle project owners have had the fortitude to press through numerous challenges and seem likely to complete the obstacle-strewn endurance event. VC Summer owners chose to abandon their project after spending $9 B. Two responsible executives served time for lying to investors and the SEC about the project’s cost and schedule performance.

It’s worthwhile to learn and remember as many lessons as possible from the AP1000 project experiences. This article will focus on just one of those learning opportunities.

Knockdown Blow From Aircraft Impact Rule Imposition

The importance of regulatory stability was one of the lessons that was supposedly learned after the US nuclear plant building boom came to a halt amid spiraling costs and lengthy project delays. The industry told its cost regulators at public utility commissions and the federal safety regulators at the NRC that changing rules during construction led to very expensive changes and rework.

Unfortunately, the message that some apparently heard was that regulatory changes before the start of physical construction were okay. The four AP1000 reactors that started physical construction in the US in 2013 have taken more than two years longer – so far – to build than the four AP1000 reactors that were built in China. The Chinese reactors were first of a kind anywhere in the world while the US reactors were the first of a kind in the US with a reference plant that could be a base on which to improve techniques. (Note: Construction duration begins with first concrete pour and ends with start of commercial operations. None of the US AP1000’s have entered into commercial service.)

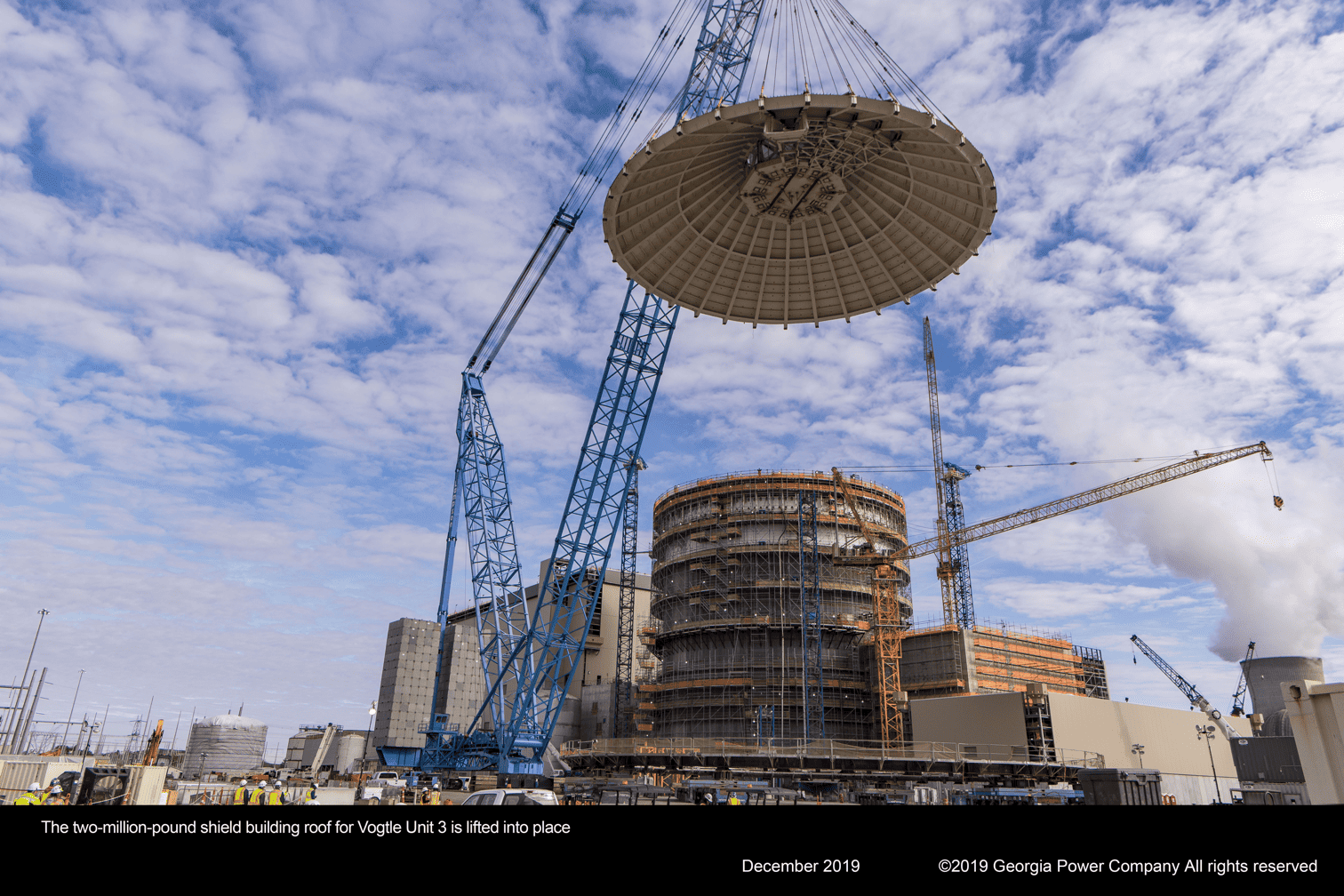

The US Nuclear Regulatory Commission published a fateful decision in the Federal Register on June 12, 2009. Titled Consideration of Aircraft Impacts for New Nuclear Reactors; Final Rule, the announcement required a major redesign of the AP1000. The decision was a seminal event in the sad saga of the U.S. AP1000 projects. It is the reason that US AP1000 plants are in a fundamentally different containment and shield structure.

Imposing a requirement to consider – and design for – a direct commercial aircraft impact on projects for which designs were already certified and for which Public Service Commission approvals had already been obtained was roughly equivalent to forcing a marathon runner to stumble and twist her ankle. Even though the injury wasn’t completely debilitating and the race could be run after taking time to treat and tape the injury, the damage to the final time for the race had no real chance of being overcome.

That major change in reactor design requirements was made despite an official NRC finding that “compliance with the rule is not needed for adequate protection to public health and safety or common defense and security.” (Emphasis added.)

The Aircraft Impact Assessment rule was not applied to any existing facility or to any facility for which a construction permit had already been issued. Here is a key excerpt from that final rule.

In making these additions, the NRC is making it clear that the requirements are not meant to apply to current or future operating license applications for which construction permits were issued before the effective date of this final rule. This is because existing construction permits are likely to involve designs which are essentially complete and may involve sites where construction has already taken place.

Applying the final rule to operating license applications for which there are existing construction permits could result in an unwarranted financial burden to change a design for a plant that is partially constructed. Such a financial burden is not justifiable in light of the fact that the NRC considers the events to which the aircraft impact rule is directed to be beyond-design-basis events and compliance with the rule is not needed for adequate protection to public health and safety or common defense and security.”

The unrecognized implication of issuing this rule and choosing to apply it to projects that had not yet been issued a construction permit is that AP1000 projects had already passed several important decision milestones that made them vulnerable to exactly the kind of unjustifiable financial burden that the NRC stated that it was trying to avoid.

Aside: I once had a conversation with a senior NRC regulator who was unapologetic about the effects of the new rule on the initial AP1000 projects. He told me that the staff had clearly communicated its intent to publish the rule and its recommendation that it should be applied to any new projects. He told me that Westinghouse should have begun revising its design well before the rule was published and that it should not have been marketing a design it knew would not be acceptable under the planned requirement. Needless to say, this conversation left me incredulous. But I was able to find several other regulators who confirmed the story on the condition that they not be named. End Aside.

Aside: It is important to understand that Westinghouse had first submitted the AP1000 design certification application (DCA) on March 28, 2002 and that the NRC had issued a design certification on March 6, 2006 based on the 15th revision to the initial DCA. The AP1000 is an evolution from the AP600, which received its final certification in December 1999. End Aside.

Though the detailed design was not yet complete, and though no concrete pours or metal forming had begun by June 2009, the plant design was complete enough to provide the basis for a cost estimate. That estimate was solid enough to pass muster with several boards of directors and two public service commissions.

That is no small task for multi-billion dollar projects, especially those that are as controversial and as visible as firm priced orders for the first new nuclear plants in the United States in more than thirty years.

Here is a quote from a document describing the Vogtle 3 and 4 projects to Southern Company customers.

- Georgia Power filed for an Application for Certification of Vogtle units 3 and 4 with the Georgia Public Service Commission (PSC) in August 2008.

- The Georgia PSC approved the need and cost-effectiveness, granting approval to implement the proposed Vogtle expansion in March 2009.

Remember, the notice applying the requirement for an aircraft impact assessment, and making appropriate design changes to mitigate the projected effects of such an impact was not issued until three months after the Georgia PSC had invested six months into the review and approval of the project as described in the NRC issued Design Certification Rule for the AP1000.

It is difficult to put a precise figure on the time that the project consortium invested into the cost and schedule analysis before submitting it to the PSC, but it was probably no less than a year’s worth of work.

As it turned out, meeting the new rule ended up requiring three more iterations on the design document and raised several issues of contention including concerns about the revised heat transfer capacity, concerns about the innovative shield building construction process devised, and concerns about the validity of the testing regime for the steel concrete composite modules that make up the shield building.

Those and other related issues were not completely resolved until the issuance of the final design certification document in late 2011, more than 2.5 years after the PSC had approved the project using the previously approved design revision.

During that delay, engineers who should have been working on the detailed design so that it could be as complete as possible before construction start were diligently working on the revisions to the regulated parts of the design that they thought was already complete.

Since the changes had a significant impact on the facility structure, they altered the seismic analysis and had a substantial impact on the design of the foundations.

Why Did Project Participants Soldier On Instead Of Complaining?

As an outside observer, I cannot explain why the damaging decision was meekly accepted without either strong resistance or a complete revision to the project cost and schedule projections. Major components of the assumptions made for the cost estimates were invalidated by the design changes required to satisfy the regulators.

There were other contributing missteps in the nearly eight years that have elapsed since the NRC issued the Aircraft Impact Rule. It is difficult to imagine a reasonable resolution to the current situation that does not include an acknowledgement – along with some kind of financial contribution from the responsible parties – that the decision had a significant and unrecoverable impact on both cost and schedule.

Note: It’s worth mentioning that the shield building design that resulted from the intensive, time-consuming effort forced by the Aircraft Impact Assessment turned out to be somewhat easier to construct than the original design. With skilled fabricators and a good QA system, the shield blocks fitted together without significant rework or other issues. Subsequent projects will benefit from this experience, but it was painful enough to help discourage new projects in the US.

Design infrastructure for the warzone instead of avoiding war – brilliant!

Great summary Rod. This one is an undisputable example of the regulator placing an undue burden on the industry.

Every time I hear about another delay at Vogtle, I just tune-out.

“I once had a conversation with a senior NRC regulator …”

His name wasn’t Walter Peck, was it? Oh wait, that was the EPA.

If he had a band it would have to carefully choose a non competitive name.

NRC regulates the peaceful use of nuclear power, yet wants security and aircraft resistance based on war zones. Those should be the the responsibility of the federal government to provide.

I hope they don’t use the conflict in Ukraine to justify additional measures.

Important post. Had either of the utilities applied for a Construction Permit in June, 2009, when the aircraft rule was issued?

Yes.

VC Summer 2 & 3 COL application was submitted on 3/27/2008.

Vogtle 3 & 4 COL application was submitted the next day, 3/28/2008

https://www.nrc.gov/reactors/new-reactors/large-lwr/col.html

So it’s Westinghouse’s fault for proceeding under the rules that were in place, but it is not NRC’s fault for processing an application under the current rules and raking in the application fees.

We all know why there was nil pushback.

a) The last thing an applicant wants to do is upset an omnipotent regulator.

b) the utilities figured they could push the extra costs on to the ratepayer.

Jack – Do you think I implied that it was Westinghouse’s fault that the rules were changed while applicable COLs and associated projects were already underway?

Of course not. I was referring to the unnamed NRCer who argued that Westinghouse should have had the foresight to operate under rules that were not yet in place. But apparently NRC itself did not follow his advice.

The above-described NRC actions were typical of what I saw back in 1973 on TMI-I. For example, Same basic rule that new changes to the Reg Guide did not apply after Construction was approved and started. However, the NRC has multiple methods of delaying and getting the Utility to accept the new rules. For example, at about 99% completion of TMI-I — All fuel on site, but not in the core and no fuel load approval, a rule was added for “Loss of Rotor” for the Reactor Coolant Pumps. The Infamous NRC rep for the TMI-II incident was also responsible for the approval of various milestones at TMI-i. He would not approve fuel load until the LOR system was installed and tested. Utility Senior executives could smell the Megabucks just a month or two away and the end of the construction loan interest payments. They knew that we would win the court fight but decided it was less expensive time and money wise to design and install a system than fight it in court and have the months long delay. The Electrical Design Engineer, the Electrical SU Engineer and I quickly devised an instrument similar to high current trip relays, but designed to detect the decrease in load. We then got approval, upon demonstrating to the Site NRC engineer that it worked. Similar actions were taken by the NRC at TMI-II on at least four systems that I am aware of during the Startup testing phase.

You seem to be describing the loss of forced flow transient/accident, the limiting case where a rotor locks, and taking the position that evolving protections for this class of transient were extraneous or gratuitous in the 1970s.

Sounds more like they were going after a shaft/coupling failure. Either way the loss of flow is going to show up thruout the primary loop. The extra sensor is at best redundant.

The point is, if an individual NRC employee can impose a requirement at will, then he is in charge of the project. If those are the rules, then nuclear is doomed to be an unimportant side show, occasionally propped up by the taxpayer when the political winds are favorable.

B&W PWR plants had/have a “Reactor Power / Reactor Coolant Flow” “Trip” which was basically redundant to the Loss of Rotor Trip. A locked Rotor would also trip the RCP on high current thus initiating the Loss of RCP Trip. All that the loss of rotor trip does is

The problem that I believe caused the TMI-II incident was that the NRC Site Engineer pushed for and got TMI -II to include the “Instrument Uncertainty” of all Reactor Protection System instrumentation AGAIN. In essence TWICE, as the original analysis they approved showed that the Instrument Uncertainty was already included. This caused the “Safe Operating Envelope” to decrease by over 5 percent and caused the Emergency Core Cooling System to begin pumping Boron into the RCS do to “Low RCS Pressure.” To the best of my knowledge no other B&W Plant has the same setpoint as TMI-II did. Again Smelling Mega Bucks the senior executives caved.

The following link may give you some more info on B&W PWRs. Note that the B&W PWR was NRC Approved without a loss of rotor trip. https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/5081441

Quality Control and Module fabrication delays are another reason for extended construction times. Also a significant loss of experienced construction staff can not be overlooked. Summer Unites 2 & 3 were used to bilk the public for the benefit of SCAMA executives. They gave themselves bonuses for good performance for plants that were supposed to cost $9 Billion and six years to build. More than $14 Billion and 11 years later the plants were only 30% complete. Three of the half dozen responsible are already sentenced to prison or have pleaded guilty.

This was the largest theft in SC state history!

The best quality control is a motivated work force, people who take pride in their work, backed up by hands on inspection by equally motivated inspectors. Westinghouse had nobody at Lake Charles where Shaw Industries was buggering up the modules. They were sitting behind a desk in Pittsburgh reading Shaw’s QA reports. This is what happens when the paperwork becomes more important than the product. And no industry is more obsessed with paperwork than nuclear.

@Jack Devanney

You are right to point fingers at both Shaw Group’s Lake Charles Facility and Westinghouse for lack of good workmanship and inspection on prefabricated modules for AP1000.

It’s worth noting where the quality modules that eventually were installed came from. Some were reworked, at significant expense in time and treasure, at the plant site in a huge, unplanned factory-like facility that had to be build from scratch. Other modules were fabricated and shipped from facilities with high quality QA programs like Huntington Ingall’s Newport News Shipbuilding and Drydock.

I just came across this document and will share it even though I have not yet fully read and digested its implications. It provides a detailed look at construction challenges from the POV of SCANA leadership – https://dms.psc.sc.gov/Attachments/Matter/a144ba69-7dd9-445e-bd41-df09527bcc9d

Another issue that I am trying to more fully understand is the impact of a “fixed price” contract. From what I understand, Southern Company initially took a nearly “hands off” approach to managing the project because they had signed a “fixed price” contract with Westinghouse to deliver the plant. Under those contracting conditions, owners can rack up heavy charges for changes if they try to direct work priorities. Of course, there is no such thing as a fixed price project with the scope of Vogtle or Summer because the supplier did not have the corporate resources to cover all of the cost overruns and ended up declaring bankruptcy way before the project was complete.

The idea that a fixed price contract means the owner must keep his hands off the project is ultra-high level idiocy. Shipbuilding contracts are fixed price with a fixed delivery date. Yet there are two teams of non-yard inspectors constantly prowling the site. The Classification Society (Class) representing the insurers and the owners own people. A smart owner makes sure that part of the team is the crew that will have to operate the vessel.

They have teh ability to stop the job, and reject tests if the find anything that is not per spec. Problems are caught early and fixed. If it’s a major subcontractor such as teh main engine, there will be three outside teams at the site, the yards, Class, and the owners.

At Shaw how many outside teams were there? Zero. I’m beginning to understand why nuclear quality stinks.

@Jack Devanney

Shaw was a nuclear neophyte. Its quality control program, especially at its Lake Charles module fabrication facility was not representative of the nuclear industry’s quality programs. Those are better represented by outages at operating facilities.

This describes the process that resulted in Shaw Group’s involvement in the US AP1000 construction projects.

https://atomicinsights.com/several-important-nuclear-energy-developments-from-the-westinghouse-press-office/?highlight=Shaw%20group%20AP1000

A key quote:

Your missing my point. All world class shipyards have solid quality enforcement programs in part because they want to keep their customers and in part because any delay to any project cascades to all the other jobs in the yard. They cant afford a screw up.

Still the insurers won’t insure a ship unless Class certifies it. The underwriters demand that Class inspectors be all over the job. They dont care how good a yard’s reputation is.

Still owners put their own team of inspectors in the yard, even if they have built a bunch of successful ships in that yard.

If I’m running Vogtle, for Southern, I don’t care how great a contractors reputation is. I don’t care how many certificates they have. I’m going to have my own guys crawling everywhere. And if they dont like what they see, they have orders to shut down the job and I’m there the next morning. All good shipowners operate like this.

I’m amazed that nuclear does not.

Jack

I’m also amazed. But you’re describing one of the reasons why there are so many people like you looking at nuclear fission technology and deciding they can do a better job deploying and operating than the incumbents.

There are plenty of obstacles, but also vast room for improvement.

Related Question – There are nuclear facilities that have been shut down. I believe the structures still remain. There are nuclear facilities that have not been completed as the VC Summer units were not completed. The losses have been taken and the bean-counters have performed their fiduciary magic. Some facilities remain. Could these existing facilities ever be reworked as new nuclear plants and used to produce energy? Have regulations made this impossible with rules such as this aircraft rule? Would this make it virtually impossible to re-power existing coal units as some companies propose?

Light water reactors are obsolete technology and much too costly to be economical. More than 75 % of the cost of construction is related to safety systems needed to protect the core. Everything from the containment, High pressure safety injection, Medium head safety injection, Low pressure safety injection, accumulators, containment spray systems, emergency heat sink water storage, service water cooling systems and multiple diesel generators are needed to protect the core. The diesels need to be up to speed and taking load within 11 seconds of start signal for most units to prevent core damage. All of this for 32% thermal efficiency and 540 F saturated steam!

On top of this, after a 3 year burn, only 4% of the fuel is consumed.

These systems are not needed for Molten Salt Reactors which burn 96% of the fuel and can produce 1100 F superheated steam.

Dr Alvin Weinberg was right 50 years ago! A man way ahead of his time!

Light water SMR’s are even worse, with some clocking in at under 30%.

I believe it’s been 10 years since I’ve seen Kirk Sorensen’s videos touting the Molten Salt Reactor. I’ve seen video presentations from the Thorium Energy Alliance adding fuel to to the Molten salt Fire. It’s been 10 years since Robert Hargraves wrote his “Energy Cheaper Than Coal” book. Molten salt reactors appear to be a better mouse trap. Why isn’t the world beating a path to build such units? I only know of the one built in China.

Eino

On November 22, 2022, Abilene Christian University applied for a construction permit to build a small (1 MW) molten salt reactor. https://www.nrc.gov/reactors/non-power/new-facility-licensing/msrr-acu/documents.html

Kairos has also applied for a construction permit to build a small scale version of its molten salt-cooled, pebble bed reactor.

Copenhagen Atomics (now a Nucleation Capital portfolio company) is operating an electrically heated molten salt prototype system to develop material performance and active component data for its 100 MWth heat source reactor.

Progress in nuclear tends to be slower than we would like it to be. It takes a lot of endurance to succeed.

One might be heartened by studying the full story of the development of the technologies that enabled the shale revolution. The effort put together all of the technologies needed to make “unconventional” or “tight” resources required several decades. First well drilled in Barnett Shale was 1981, fracked gas began making a significant contribution to US energy supplies in ~2007.

I guess Moore’s law or the equivalent thereof does not apply to nuclear. Thanks for the response.

The shield building is just a steel concrete cylinder. Not exactly rocket science. There’s perhaps a few million $ of concrete and steel in it.

There have been 20000 million $ in cost overruns.

Clearly the shield building issues are minor symptoms of a much more pervasive illness.

The AP1000 containment and shield building is way too clunky anyways. Using containment as surface for cooling limits heat transfer, made worse by the need for significant steel thickness. Using lots of valves to acuate a reservoir of water in the seismically worst possible location isn’t brilliant either. I do like the steel sandwich walls with concrete fill. That is basically a triple containment. They could have used that as containment and shield in one. Higher strength would allow increased design pressure so a shorter building. Use modular passive heat exchangers connected to containment in one side and big water pool on the other. No valves, good seismic profile, lower cost, better cooling – and you get triple containment to boot (steel concrete steel).

Is an aircraft crashing into a containment building a credible disaster scenario? Obviously, there would be a lot of damage to equipment not in containment, but it hardly seems likely that an airliner could demolish the containment building and cause a huge, Chernobyl level release of radioactive materials. This seems to me like a bow to the anti-nuclear industry, which insisted after 9/11 that all nuclear plants be shuttered owing to the extreme likelihood that the next terrorist event would be an airliner crashed into a nuclear site.