Tour of NuScale control room and test facility

Disclosure: I have a small contract to provide NuScale with advice and energy market information. That work represents less than 5% of my income for 2014.

On October 20, 2014, I had the opportunity to visit NuScale’s facilities in Corvallis, OR. Though the company now has offices in three cities, Corvallis, the home of Oregon State University, is the place where the NuScale Power Module has been conceived and refined.

Unlike the other participants in the race to develop small modular reactors that can be licensed and sold in the United States, NuScale is a focused start-up company with many similarities to other high tech start-ups. It grew out of a university research project, has been through several rounds of capital raising, maintains a working relationship with the university that initially nurtured its development, and has located its offices in an available vacant building with a motivated landlord.

In NuScale’s case, the available building was in excellent, move-in condition. It is part of a multi-building campus owned by HP that was once a bustling center for designing and manufacturing personal printers and their associated ink cartridges. In 2011, NuScale was one of the first tenants to occupy space in its building, which was already set up as an engineering design office. NuScale’s occupancy was part of a local reuse program. Desks, cubicle dividers, and even chairs were ready and waiting for the new creative occupants.

My first stop was in Jose Reyes’s office for a quick update. Jose is NuScale’s Chief Technical Officer and one of the company’s cofounders. I’ve known him for several years, our first official interaction was when he and Paul Lorenzini were my guests on Atomic Show #100 in August 2008.

Reyes began by telling me that NuScale’s head count is up to 380, including contractors serving as staff augments. About 200 of those work in Corvallis. As a fully owned subsidiary of Fluor, NuScale receives ongoing investments through the budgeting process. There are numerous positions still open; the company has recently been adding several people every week.

So far, the total project spend has been about $230 million. NuScale and the US Department of Energy recently finalized their cost-sharing agreement through which the DOE will provide grants of up to $217 million over a five year period to assist in defraying the additional costs that are imposed on the leader of any new nuclear technology development, subject to annual appropriations.

In the US, the first-of-a-kind leader must pay the Nuclear Regulatory Commission costs associated with reviewing and producing positions on new concepts. All followers get to use those established positions without incurring the $279 per professional staff hour fees or having to pay its own people to devise the concepts and provide the technical justification that results in NRC approval. In the case of NuScale, some of the ground breaking concepts include natural circulation and control room designs that enable different staffing concepts than used in existing reactors.

NuScale’s testing and licensing program are moving along. During the next year, Reyes expects that his team will be submitting a number of topical reports to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. In NRC lingo, there is a significant difference between a topical report and a technical report. Companies submit technical reports as a way to keep the NRC informed about various aspects of a design, but the NRC is under no obligation to comment or respond.

In contrast, the NRC reviews and comments on topical reports. If appropriate, the NRC may formally accept a topical report as suitable to be used in a licensing and provide limiting conditions under which the report may be used. The topical report process will provide the company with better understanding of the NRC’s position on certain key issues.

According to Reyes and the schedule that has been submitted to the NRC, NuScale should be ready to submit a high quality application before the end of 2016. Since the company first notified the NRC that it intended to submit an application for a design certification in 2008, it should be apparent that working through the licensing process in the United States is no job for people with an impatient, “git ‘er done” mentality. It should also be apparent that the current situation must be improved.

NuScale has begun developing its supplier base. As a Fluor subsidiary, it has access to a large, world-wide supplier network, but some of the components of the NuScale Power Module will require expansion of that supplier base. Reyes indicated that the company believes there is sufficient capacity for key items for building one or two power stations in a reasonable period of time, but additional investments in facilities will be required to enable a higher throughput.

The company has hosted a couple of supplier days already; most of those have taken place in the northwest US, which is where NuScale intends to concentrate its deployment efforts.

The next stop on the tour was a visit to the control room prototype. It is in a large room with the same footprint as will be available in the actual power stations. The ceiling is a bit lower; the room is limited by a ceiling height available in a commercial office building.

The main control panels are arranged in a horseshoe configuration with thirteen individual desks and screen groups. There is one desk/screen group for each unit and a larger one to operate and monitor shared systems like circulating water and the large pool in which all of the modular containments will reside.

One of the primary goals of the facility is to develop the concept of operations and human factors program to support the rule exemption request that the company will need to submit. The current rule that specifies plant operations has no provisions for more than 3 units on a site or more than 2 units controlled from a single control room. NuScale is not yet certain how many operators it will need, but its initial position is to attempt to reduce the work load to the point where it is manageable by an operating crew that is the same size as the one used at existing nuclear facilities.

Because I have not signed any non-disclosure agreements with the company, the screens NuScale showed me during my visit were generic, but they provided a good understanding for the direction that the company is taking to streamline operations, automate functions where desirable and provide clear, understandable indications.

My tour guide and I had a good discussion about NuScale’s plan to provide intelligent alarms that do not overwhelm operators with unnecessary noise and distraction. As an example, he mentioned that some control rooms provide dozens of alarms during a typical turbine trip even though all of them are reporting conditions that are expected to happen whenever the turbine goes off-line.

Several experienced senior reactor operators have joined the company’s team and are working with the system designers to achieve a complete systems approach that takes into account indications, alarms, layout, controls and human skills.

The final tour stop required a short drive to the OSU campus, where NuScale’s test loop is hosted. Reyes began that part of the tour with some background information about the testing and scaling techniques he and his team learned as contractors for the Westinghouse AP600 and AP1000 passive cooling testing program. He described the program schedule and the way that they used temporary trailers, university students and contractors to achieve a six-day, 24-hour per day testing regime to produce valid results in a cost effective manner.

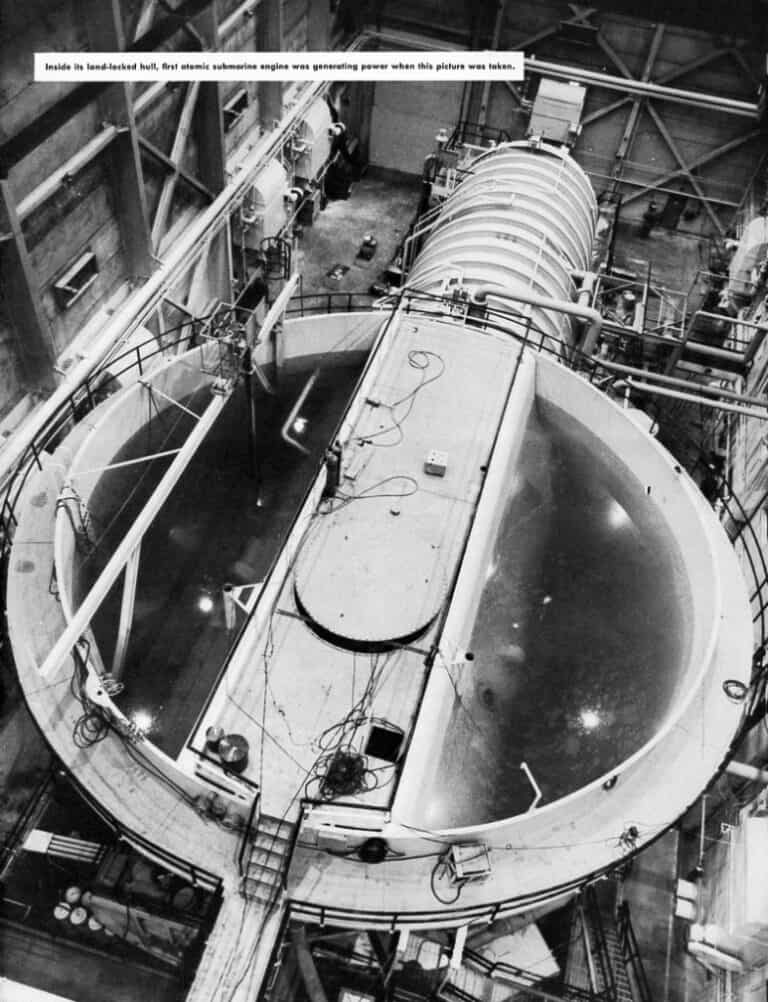

Then I had the good timing to be one of the first people to tour an in-progress modification of the NuScale testing facility, which was undergoing a major revision as the result of recent system redesigns. Having a good familiarity with mPower’s Integral System Test (IST) facility, I was surprised at the substantially more compact test loop that Reyes and his team had designed and built. The facility was inside an existing laboratory building that is about 30 feet high and has a tall garage door similar to what you might see at a fire station.

Reyes described the effort involved in producing reliable scaling computations and explained that there are two different paths that can be taken to build system test facilities. One is to use relatively simple, well-known calculations and produce a full height, reduced diameter facility. The other path involves more work up front and some specialized computational techniques, but results in the ability to reduce scale in other dimensions while still providing valid results predicting full scale system performance.

The full height path is much more expensive in terms of component construction and installation; it often results in a special purpose building. On the plus side, the one-of-a-kind facility will create some temporary engineering, architecture, construction and manufacturing jobs.

As a start-up led by a professor at a major university, NuScale could obtain skilled engineering services for the up-front calculations relatively cheaply. It did not have the capital to invest in manufacturing and housing a full height test loop. As a focused start up, the company had no established divisions vying to contribute their particular core competencies to a shiny new project that had top-level support from a large, long-established corporation.

They also did not have local civic boosters interested in creating new jobs thinking of ways to add work or offering to spend economic development money for facilities targeted at attracting additional businesses.

NuScale’s new test loop will be ready for operations in early 2015. It still needs a few finishing touches along with the installation of lagging (insulation) before it can begin operations. However, the trailer that will house the control room for the facility has arrived, most of the piping connections have been made, and instrumentation installation is well under way. The revised test loop will provide NQA-1 quality data from a data acquisition and control system taking inputs from more than 500 instruments.

After an informative visit, I headed for the next stop on my whirlwind visit to the Pacific Northwest. That leg involved a journey on one of the most scenic interstates in America, especially for someone who is obsessed with ultra-low emission energy production systems. More to follow.

Very interesting. I am taking a trip out to Portland and Seattle in November, and was thinking about trying to take a very similar tour.

For your next stop, I am going to guess that maybe Bellevue, Washington could be involved?

Can someone explain to me a little bit of what sort of testing has/will be occuring? I presume that they cannot actually load nuclear fuel into the reactor, to actually run it, but I would imagine that they can do things like electrically heating water and turning it into steam in the primary loop, to do pressure testing, make sure pumps work as expected, hydrodynamic flow works as expected, scram works as expected, electrical systems work, control systems work, and so on. Pretty much every aspect that is NOT radiological in nature?

But, how do they test things like shielding, to make sure the reactor won’t lead more radiation than it’s supposed to, behavior of equipement and electrical systems in the presence of a high radiation flux (whether neutron, gamma, alpha, or beta)? And so forth?

I suppose this preliminary test loop, maybe, doesn’t concern itself so much with the radiological behavior – that will come with a later reactor, once the NRC has reviewed all the non-radiation-related aspects of the system? I suppose with the testing being done on this reactor, the NRC will make a decision on whether to allow a working prototype to be constructed somewhere (e.g. at a National Lab site?) where it can really be tested with fuel loaded?

Also, I’m curious – for the initial reactor protype they’ve built on campus – I was thinking about this the other day – not in the context of NuScale, but just nuclear reactors in general. I formulated the situation, in the form of the following question: “When does a nuclear reactor become a nuclear reactor, and require NRC licensing to be legal?”

That is, I would presume, so long as you don’t seek to purchase/obtain and load fissile material into a nuclear reactor, you probably *don’t actually need* any permission from the NRC to build a device that is basically non-nuclear in nature if no fuel is loaded into it? It’s just an electromechanical device without any fissile material, right?

Jeff,

The test setup at OSU uses electric elements to simulate a radioactive core. There is another electrically heated test reactor model of the Westinghouse AP600 there.

OSU houses a pool type research reactor which has a nuclear core.

Rod, any idea what software they are using for the controls? ABB? Ovation?

DW

David Walters, please go to page 23 here:

NuScale Plant Design Overview

http://pbadupws.nrc.gov/docs/ML1326/ML13266A109.pdf

Also read:

Instrumentation and Control Diversity and Defense-in-Depth Technical Report

http://pbadupws.nrc.gov/docs/ML1218/ML12188A581.pdf

Details about the technology platform likely cannot be released in a public forum.

Great! All those past examples of natural circulation bode well for the licensing of this new reactor.

I wonder if this will be simple enough that you can run it with a Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) or multiple PLCs. It should be much less sophisticated than other commercial reactors.

Is it more difficult to create the design for this new reactor or to properly document the design basis for government approval?

NuScale looks like a really simple and safe design … my fear is that the main feature (no pump on the primary side), will be the Achilles’s heel, as you need a certain temperature gradient to start the natural circulation. Also, the lack of primary pumps can’t help during different transients that could impact the stability of the TH parameters.

Just my 2 cents ….

I haven’t looked at NuScale’s licensing submittals but I would guess that the drawbacks to natural circulation are mainly economic – the low core power density and perhaps a limit on starting up the plant since pump heat is used to heat up the RCS. Do they use nuclear heating to go from cold shutdown to rated power? Or use the secondary side via auxiliary boilers or perhaps the other operating modules?

Reactor Coolant Pumps are often a liability in a transient. They are a source of leakage, require power (loss of which precipitates a transient), their heat must be removed. In SBLOCAs they are often required to be stopped. On the plus side, their heat does limit the cooldown from a MSLB.

NuScale also doesn’t have to analyze the startup of an RCP in an idle loop accident.

FermiAgec stated:

“I haven’t looked at NuScale’s licensing submittals…”

NuScale licensing submittals can be obtained from links at this web page:

http://www.nrc.gov/reactors/advanced/nuscale.html

FermiAged asked:

“Do they use nuclear heating to go from cold shutdown to rated power? Or use the secondary side via auxiliary boilers or perhaps the other operating modules?”

Section 3.8 in NP-ER-0000-1198-NP, the NuScale Plant Design Overview, Revision 2, available in the public domain at the web site of the US NRC states:

“Additionally, during the power module startup process, the CVCS will be used to add heat to the reactor coolant to establish natural circulation flow in the reactor coolant system.”

So that is about the size of the final product? In the brochure it looks similar. Its smaller than I thought, 95 percent capacity factor as well and that’s probably going to be on the low end. ( http://www.nuscalepower.com/overviewofnuscalestechnology.aspx ).That is awesome.

I am even more excited by the news I saw in your twitter that Coquí RadioPharmaceuticals is opening a facility right in Alachua, my area. It will not only provide needed medical isotopes but also needed high quality jobs and important technology for this region. I suspect it will also be beneficial to UF’s nuclear program. ( http://www.nuceng.ufl.edu/nuclear-program-expands-welcomes-new-director-renovates-reactor/ ).

Very useful information in this article. NuScale would do well to provide this sort of information themselves on a regular basis to improve information for policymakers. Otherwise I hope they engage you to do this for them as this is invaluable to promoting the technology.

What control components are needed for the reactor? It has two reactor recirc valves and two reactor vent valves. It has rod control. It will need rod position indication. Temperature and pressure transmitters will be needed. Nuclear monitoring will be needed. It still has a pressurizer so I’m guessing electric heaters to the pressurizer may be needed. How much redundancy will be needed for these valves and controls? Will it be like BWRs with one out of two taken twice or maybe two out of three? Is there a simplified P&ID out there amongst the links?

Are they AOVs or MOVs?

Penetrations at nuke plants were always a problem. I wonder how this reactor will deal with that. Maybe, they haven’t got that far yet.