I do not hate oil companies; I hate their business model and the way they dismiss nuclear energy

I do not hate oil companies, I hate their business model. I hate the fact that they are capturing a vast portion of the world’s wealth and power by extracting an ever higher price for essentially the same product that they have been selling for 100 years with few technical improvements that make it more valuable for their customers. I hate the fact that their recent marketing materials disrespect the only energy source that can give their own product any real competition.

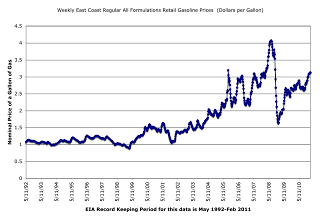

Though there has been some innovation in the back end of the business of finding, extracting, refining and delivering the end product, the material that I pump into my car every couple of weeks is nearly identical to the liquid that powered Henry Ford’s Model T. It is the same fluid that I remember my Dad purchasing for less than 25 cents per gallon during our 1972 vacation, that I remember purchasing for 50 cents for my 1973 VW Beetle on the day I passed my driving test, and that my 27 year old daughter remembers purchasing for less than $1 when she started driving. Last week, I paid $3.25 for a gallon of gas, 13 times more than exactly the same amount of the same product cost just 40 years ago.

There has certainly been inflation over that time, but many of the products that cost more today are substantially improved. For me personally, there is an interesting numerical parallel between the price of gasoline and the price of of another basic commodity – shelter. The home I grew up in cost my dad and mom about $25,000 in 1962. The home I recently purchased cost something close to 13 times that amount. There are a number of similarities but also some substantial differences between the two products.

Here are the similarities. At the time of purchase, both homes were about 2-3 years old and in subdivisions that are still under construction. Both neighborhoods were farm land before becoming subdivisions. Both were solidly in the middle class and both purchasers – my dad and me – were employed as middle management level engineers who value solid workmanship and up to date devices.

Here are the differences. My house is about twice as large, the exterior is brick instead of painted cinderblock and the lot is more than twice as large with a panoramic view of the Blue Ridge mountains instead of our neighbors back yard. We have central air conditioning, improved floors, improved countertops, an installed dishwasher, and several other amenities that were not even available in 1962. Part of the “inflation” in home prices has included substantial product enhancements. In the meantime, gasoline is still gasoline. Because of the fact that it contains more ethanol than it did in 1972, it actually contains less of the characteristic that customers really want – stored energy.

Though oil companies frequently claim innocence for the sharp, but erratic increases in the price of their product during the past 40 years, they love to brag about the financial results that those price increases provide. Since they are selling the same product from the same refineries, often extracted from the same wells that have been producing for several decades, market price increases simply fall directly to the bottom line. Those pumped-up bottom lines provide plenty of justification for increases in management and executive salaries, even though the corporate leaders avoid taking any responsibility for price increases. Oil and gas company managers and executives enjoy getting credit from investors for good results, but they do not like getting blame from customers or politicians for higher prices.

The oil company business model of driving up profits by enjoying market driven price increases really looks bad when compared to the high technology industry that has given us incredible advances in capability with ever lower prices. For a long time, I tended to pay about the same each time I upgraded my personal computer; I just bought more and more computer capability with each replacement cycle.

I broke that string on my last purchase with an iMac that cost less than $1600 after shipping and taxes. The two year old “all in one” that sits on my desk has a gorgeous 24″ screen, a screaming fast processor, a 500 GB hard disk, and 4 gigabytes of main memory. That is an enormous set of improvements compared to my first “all in one” Mac Plus with its 9″ greyscale screen, no hard drive at all, and a grand total of 1 megabyte of main memory. That very limited capacity machine cost me $2200 in 1987 more than 25% more than the machine I now own.

John Hofmeister, a former President of Shell Oil, is the author of a book published in May 2010 titled Why We Hate the Oil Companies. I purchased the book for my Kindle yesterday, partially on the recommendation of Gail Marcus, the author of the excellent blog titled Nuke Power Talk. Gail wrote about Hofmeister’s book before it was released; obtaining and reading a copy has been on my “to do” list for over a year. I am a procrastinator.

Though Hofmeister and I have had our initial views about energy shaped by the same events – the Arab Oil Embargo of 1973, the decades long parade of politicians promising energy independence, and the rapid run up in natural gas and liquid petroleum prices in the period from 2005-2008 – we saw those events through very different lenses of education and personal experience. We run in different crowds and have different values; that have also had an influence on our perspective.

Hofmeister most likely started off in roughly the same middle income economic status as I did; he mentions that he fell in love with internal combustion engines while driving a tractor at age 11 on a farm owned by a landlord. My dad came from farming stock, but he was an engineer and middle manager by the time he started a family.

By the time of the Arab Oil Embargo, Hofmeister was in a management training program for a Fortune 500 corporation. He held a series of ever higher level jobs while climbing the corporate rank structure. Though he eventually wound up as a top executive at a multinational oil company, he had no technical training or experience – he was a political science major before becoming a business manager.

In contrast, I entered a leadership/management training program a few years after the 1973 Arab Oil Embargo when I accepted an appointment at the US Naval Academy and started plebe summer in 1977. I served in some tough sea duty assignments and made good progress up the promotion ladder until 1993, when I left active duty to start a company whose mission was to make a measurable improvement in the world’s energy supply.

Along the way, I have stood countless watches with smart people who could not afford to attend college, worried – as my business struggled to overcome decades worth of carefully instilled fear – how I could possibly afford to send my children to the level of college that their academic performance warranted, broken bread with high school dropouts who work with their hands in open air factories, and managed a small plastics factory where the electric power bill was about twice my salary. I also had the opportunity to have some input on the Navy’s fuel budget at the height of the 2008 peak in prices and during the period subsequent to the recession driven price reduction.

Like Hofmeister, I started off with a non-technical undergraduate degree, but early in my career, I obtained some of the best technical training available in the world by successfully navigating the Navy Nuclear Power training pipeline. While Hofmeister obtained first-hand experience as a power generator by operating a 50 hp reverse wired motor connected to an old water wheel that was part of an old mill property he and his wife restored, I obtained my power generation experience in several assignments with direct responsibility for an fission heated machine producing hundreds of times more power. Like Hofmeister’s water wheel, my ship’s atomic engine also produced no emissions. Based on Hofmeister’s description of his power plant, I am pretty sure it was comparable in size to the one that drove my submarine – when you include the required fuel sources.

Though Hofmeister includes some mildly positive comments about nuclear energy; he does not indicate any deep understanding of the technical superiority that fission has compared to fossil fuel combustion. He knows some things about nuclear energy; but he does not grasp their implications.

For example, he quotes William Tucker’s book titled “Terrestrial Energy” as pointing out that uranium fission releases 2 million times more energy per equivalent fuel unit than fossil fuel, but he does not understand to the core of his being that means that a ship powered by uranium can be designed so that it never needs to be refueled. He does not grasp intuitively that it means a handful of uranium contains as much energy as thirty tanker trucks full of oil.

He describes the visible and irritating air in China, but does not mention that the technically competent Chinese leaders have decided to build nuclear plants as fast as they can in order to eliminate coal generated pollution. He talks about how the US will never eliminate its need for coal generated electricity and also describes how France generates more than 80% of its electricity from nuclear. But he never puts the two facts together and investigates why France managed to achieve that success even though it was far behind the US when it started building. He does not point out that the US would have had an essentially coal-free power system by 2000 if it had just kept building nuclear plants.

Hofmeister recognizes that a failure to expand supply drives prices up. He acknowledges that oil company managers are often focused on their own short term desires for profits. He even recognizes that political decisions often put an artificial limit on the supply. However, he has blinders when it comes to putting together those disparate comments. I would have thought that a trained political scientist who has worked his way up through corporate ranks would recognize that business leaders are also political beings. They will who do whatever they can to use carefully selected words to alter political decisions to favor their own interests.

Hofmeister does not address the fact that a reasonable person with critical thinking skills might wonder if just maybe, the political decisions that resulted in restricting supply and drive up prices might have been encouraged by business leaders whose companies make more money when they sell their products a higher prices. He describes how painful it was to be forced to swear in before testifying to Congress about high prices, but he never mentions that those same high prices directly resulted in expanding his personal wealth.

I will give Hofmeister the benefit of the doubt. My friend Gail thinks highly of him. I will assume that he does not know that at least some oil industry leaders have known about the potential of nuclear energy to provide better and more efficient energy since at least 1956. That was when President Eisenhower sent a “wealthy Texas oil man” named Robert Anderson to explain the facts of life to King Saud and Prince Faisal as part of an effort to defuse the Suez crisis. The encounter is described on page 488 of Daniel Yergin’s classic work on the oil industry titled The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power.

Aside: I think it is one of the most enlightening passages in the 788 page book. End Aside.

The objective was to get the Saudis to apply pressure on Nasser to compromise. In Riyadh, Anderson warned King Saud and Prince Faisal, the Foreign Minister, that the United States had made great technical advances that would lead to sources of energy much cheaper and more efficient than oil, potentially rendering Saudi and all Middle Eastern petroleum reserves worthless. The United States might feel constrained to make this technology available to the Europeans if the canal were to be a tool of blackmail.

And what might this substitute be, asked King Saud.

“Nuclear energy,” replied Anderson.

Neither King Saud nor Prince Faisal, who had done some reading on nuclear power, seemed impressed, nor did they show any worry about the ability of Saudi oil to compete in world energy markets. They dismissed Anderson’s warning.

Like the Saudi’s in 1956, I think that Hofmeister might have read a few things about nuclear energy, but he has never seen first hand how a tiny amount of fuel can drive a powerful submarine through the water for decades without new fuel. He has never lived for months at a time sealed up with a power plant and then compared that clean air experience with trying to breathe in a polluted place like Beijing, China or Washington, DC on the third day of a temperature inversion.

Hofmeister may not realize that there is virtually no physical limit to the amount of nuclear heat that can be made available to the world’s energy market – he may not realize that political constraints on the magnitude of its contribution are most likely to have come from pressure applied by people with a vested interest in constraining supplies to drive prices higher. Remember, the business model in the oil and gas business is selling as much of the same old product as possible at a price just a fraction below that which will send the entire world into a recession.

I am pretty sure that King Saud and Prince Faisal were far more worried in 1956 about the looming expansion of nuclear energy than they let on. They knew from direct experience that increased supplies of energy sources led directly to reductions in energy prices and that lower energy prices were not good for their personal bottom lines. My guess is that the warning that Anderson pr

ovided resulted in a lot of behind the scenes planning and action implementation. Hofmeiser came into the business much later; all of the talking points about how expensive nuclear plants are and how the environmentalists have campaigned against them for so many years – just like they do all other forms of reliable energy – had already been written. My guess is that those talking points were in the documents provided to him as reading material to get up to speed on his new industry.

People who are put in charge of a technology-driven company without having risen through the ranks of that industry, have little time to develop more than a very shallow understanding of their new industry. Though executives are “quick studies,” the knowledge they obtain often comes from briefs provided by well meaning staffers. Having spent ten years providing digested knowledge to high ranking officers, I recognize the mile wide and inch deep nature of the knowledge that they accumulate in order to survive all of the pressures of their position.

On at least one topic Hofmeister and I agree – he is the founder of Citizens for Affordable Energy. American prosperity has been enabled by access to some incredibly abundant and easy to obtain energy fuels. We need laws and regulations that allow energy accessibility and seek to make clean energy the affordable kind. The difference between us is that I have seen the light – the Earth was endowed from its initial creation with all the energy fuel that mankind could ever desire.

We have access to a terrestrial version of the process that converts tiny quantities of mass to incredible quantities of energy. It is a process that has similarities with the one that allows the sun to provide heat and light from 93 million miles away for what is, for humans, an infinite period of time. Our earthly version of that power source is compact enough to be put into small machines that can be distributed to most of the places where their power is needed.

We do not have to depend on an unreliable, 93 million mile transmission path that is often shaded by our own planet. We do not have to depend on organic materials that took hundreds of millions of years to ripen into petroleum with the help of the pressures and temperatures of geologic processes. We do not have to depend on rapacious, multinational corporations that see increasing prices as their pathway to prosperity.

We also do not have to develop a complex industry to handle our gaseous waste products if we simply acknowledge and take advantage of the fact that we have been gifted with an energy source that does not produce any gaseous waste to process in the first place.

Semi-OT, but why do there exist peak-oil doom mongers who argue that exhaustion of the world’s oil supplies will inevitably lead to the death of the bulk of the world’s population, without even considering nuclear fission as an alternative?

Is belief in the StormSmith hack job really that all-pervasive?

A really informative post. This line is particularly well phrased. “the Earth was endowed from its initial creation with all the energy fuel that mankind could ever desire”. You elegantly express a concept which is not well known. I have come to believe that it is more effective to express the energy density of nuclear fuel in terms of volume rather than weight. Our minds eye pictures the volume occupied by a substance. I recently wrote an essay entitled A Recipe for a Sustainable Future. One section, Comprehending Energy Density of Fuels follows:

Nuclear fuel energy density is 50 million times that of coal on a volume basis. This example may help us conceptualize the tiny amount of nuclear fuel needed to run a 1 GW reactor for a year.

The energy density of nuclear fuel (uranium or thorium) is 2 to 3 million times that of coal on a weight basis. Uranium or thorium is 19 times heavier than coal, so when compared on a volume basis we must multiply the 2 to 3 million times 19, which gives us about 50 million times more energy than coal.

One ton of coal fills my Nifty Fifty pickup bed to a depth of one foot. That coal fed into a coal fired power plant will generate about 2400 kWh which is the amount of electricity used in two months in the average American home. One ton of uranium or thorium loaded into a breeder reactor that burns up 100% of the nuclear fuel will last for one year producing 8 billion kWh. Since nuclear fuel is 19 times heavier than coal, my pickup box filled to a depth of one foot would contain 19 tons, enough nuclear fuel to keep a 1 GW reactor running for 19 years. Or stated another way a year

For one of the nastiest substances on earth, crude oil has an amazing grip on the globe. We all know the stuff is poison, yet we’re as dependent on it as our air and water supplies — which, of course, is what oil is poisoning. Shouldn’t we be technologically advanced enough here in the 21st Century to quit siphoning off the pus of the Earth? Regardless whether you believe global warming is threatening the planet’s future, you must admit oil is pass

DV82XL: Are you completely clueless in regards to all the other uses crude oil has in our society? Plastics and fertilizers have a rather large impact on what we eat and how we communicate via computers, phones, radios, and TV sets. It’s plain stupid to label oil as some sort of disease or addiction unless you would rather live in a cave or hut hunting and gathering for your sustenance.

We have a large problem, it’s ignorance and it was released into our society by persons looking to keep us poor and dependent on them for basic energy and transportation needs. Is it not bad enough that most of the politicians today are greedy lawyers whose only goal is to keep power and dependence in DC at the expense of economic freedom, we have a populace that is so gullible they believe in peak oil theory, nuclear energy is BAD in any way, shape or form, clueless as to what hydrocarbons contribute in addition to cheap fuels, socialism is a good thing capitalism caused the mess we’re in and worst yet AGW scam in which theorists that aren’t versed in all the necessary disciplines of solar climatology, physics, hydrodynamics, thermodynamics etc and even a couple of politicians that bordered on flunking basic science while in college lead the way into the abyss all the while padding their nest with money that they unjustly deserve.

I’d be terrified as an investor to ever sink money into development of type IV nuclear power generation when we have such aforementioned ignorance in places of power. Our government subsidizes ethanol industry that consumes not only our food stuffs but oil at 1.5 times the rate it produces fuel not to mention just how corrosive that fuel is for our current vehicles. In short, we’re screwed big time thanks to special interests that have taken hold of education and milking it for everything possible benefit the unions can think of which wouldn’t be to bad accept the product they’re producing is unfettered perpetual ignorance.

Now, who’s up for American Idol and Survivor?

No I am not completely clueless in regards to all the other uses crude oil has, my remarks were in the context of burning the stuff to release energy. While there are other important uses for oil, if those were the only ones, available supplies would last for centuries. Not only that, but coal and gas can also be used as feedstock for the processes you mentioned.

The issue with petroleum is using it as a fuel.

Interesting post as always Rod, but a few things. First, you make a fundamental error when trying to compare the price of a scarce commodity – oil – to less commoditized products (computers, etc.) The fact is, oil may be the same, but like other minerals, there’s less of it every year, not more. Computers are cheaper and more powerful every year because market forces produce new and better versions every year. Monopoly forces aside for a moment (which I admit tend to have a pretty big thumb on the scale), as demand rises and supply stays fixed, price increases. It doesn’t matter how “old” oil is, because demand keeps going up.

The one point you could make here is that oil prices perhaps do not directly follow the way minerals economics works in other fields – like gold, silver, and yes, uranium – where price increases tend to drive further exploration (increasing available supply and thus acting as a check on price). Given the fact that oil production exists largely as a cartel, the economics of exploration work out differently. But that is largely outside of the control of the oil companies themselves.

Fundamentally, I remain optimistic for the “long game” of nuclear. While I too am disappointed at the slow pace of development in new nuclear plants, ultimately even if the inevitable bait-and-switch on “cheap” natural gas comes, nuclear technology will still be around. It may be a painful transition period – the same painful transition that drove the French to move almost exclusively to nuclear energy for their power – but I think history shows the transition can be made. Thus, I think one can remain cautiously optimistic about nuclear, even with the assault of “cheap” fossil sources right now.

That being said, I don’t think one can simply point to France and China and blithely ask why we can’t do it here. This is not a technical question; it’s a political and economic one. Right now, the way our utility industries are organized, most lack the capitalization to build more than one or two units; although the potential for clean, reliable power is extremely high, the fact is for many this is a matter of putting all of one’s eggs in one’s basket. (On the other hand, Idaho Samizdat had an interesting perspective on perhaps new business models for utilities to invest in nuclear the other day, analogizing to the spice trade.) The fact is, in places like China and France, energy is essentially a federal monopoly – something fundamentally at odds with the model for energy production here. In that sense then, it’s asking the wrong question, which isn’t whether we can technologically do it, but how we can structure incentives and regulations such that there is an ability for the private market to get the funds together to accomplish it. Like it or not, the federal government is unlikely to be directly entering the general commercial electricity production market anytime soon. (Although one could certainly argue about the impact of generous federal subsidies for so-called “renewable” sources…)

@Steve – my point is that a substantial portion of the petroleum industry’s customers do not really want “oil”, they want heat energy. Sure, internal combustion engines need a certain kind of chemical in order to function, but I can use electricity to heat my home just as easily – if not easier, more safely and cleanly – as I can use natural gas, coal, wood or heating oil.

As I continue to point out, the very first applications of nuclear energy took markets that were previously dominated by oil – submarine propulsion, electrical power generation in Florida and the northeast US, and aircraft carrier propulsion. There are still some nuclear district heating systems in use, and the US Army had an interesting small reactor program where the reactors were specifically designed to replace diesel fuel.

When you see oil as just one of many sources of mostly fungible heat energy, like I do, you will see why I say what I say about the business model and the sales job that has convinced customers and politicians that we are addicted to oil as a specific product whose suppliers deserve special treatment and deference.

They are just big, fat, wealthy companies that do not employ very many people compared to their revenue. They selfishly do not care much if their actions harm the entire economy – unless they go to far and actually impose so much pain that their addicts begin to fight back.

Fair enough, @Rod. I too agree that it’s pretty dumb to use fossil sources as a source of heat per se, when we can do it as cheaply (or more so) with electricity, e.g., nuclear. I do think fossil fuels have found their place however due to their energy density (outdone only by nuclear) and ease of transport – the latter of which has made fossil sources ideal for small combustion applications (like cars). I do wonder how the numbers break out for large combustion, such as the major issue you point out: shipping. That is, I wonder what the day-to-day fuel costs are for shipping versus the immediate sunk cost for one nuclear reactor, and whether those dynamics are poised to change? I also wonder how much of this comes from the (in)ability to eat up-front costs, despite the savings on the back-end (which I would guess are considerable).

@Steve – I have been writing about nuclear power for shipping applications for a long time. That was one of the initial markets I had in mind for Adams Atomic Engines, Inc. Here are a couple of links you might find interesting:

http://adamsengines.blogspot.com/2009/07/seeking-simplicity-finding-complexity.html

http://www.atomicengines.com/ships.html

http://www.atomicengines.com/Ship_paper.html

The primary application in which liquid hydrocarbon fuels shine isn’t energy density so much as power density in small engines. It is this alone which will inspire the development of nuclear-derived synfuels.

One thing impressive about liquid fuels is the rate of energy transfer (i.e. filling up your tank). While I agree if you goal is moving down the road regardless of energy source, fossil fuels are best used for other purposes. Nevertheless, no one wants to wait xxx minutes/hours refilling the tank (what ever that tank may be) to achieve the goal of continuing to travel. This is why I think nuclear-derived DME is the better way to go.

What if there was a way to deliver power to you as you are driving? I have been thinking about the potential for electrifying limited access highways. Technically, it would be a challenge, but just imagine how it would be if we could deliver electricity to individual cars in a way not dissimilar from the way electric trains work. That way, you a 40 mile battery might be plenty for almost any kind of use.

What if there was a way to deliver power to you as you are driving? I have been thinking about the potential for electrifying limited access highways. Technically, it would be a challenge, but just imagine how it would be if we could deliver electricity to individual cars in a way not dissimilar from the way electric trains work. That way, you a 40 mile battery might be plenty for almost any kind of use.

I apologize in advance for knee-jerk reactions to your vocabulary, but here I go.

Oil isn’t controlled by cartels – anymore. It was up until around 2005 when OPEC, the final relevant oil cartel, lost its reserve capacity meaning that the price is now fully in the hands of supply and demand. If any cartel could control the price they would – there are more than a handful of powerful organizations that would like to.

Oil is dissimilar to gold and silver in that it depletes but similar in the process of exploration and extraction. The abundance vs. extraction cost is a critical measure for the market stability as peak production is passed for all of these. And indeed, computers, as finished products have a declining price, while the materials used in the power supply components increase in cost continuously. A car can similarly be said to be getting more miles per dollar while the cost of oil increases.

In response to your federal monopoly talk, I just want to echo the opinion I’ve heard from GE executives that a “sovereign commitment” is needed for new nuclear and advanced nuclear technology to succeed in the US. I really do think there are a number of valid business models that government can choose to accomplish the goal, but the difficulty with relatively simple loan guarantees shows how a government that can’t make up its mind can cause the entire thing to crash into the ground.

@theanphibian – the recession drive reduction in supply has given OPEC back its reserve margin. Members have also learned that they can make more money on less volume when the prices are kept high through market discipline.

With regard to utterings from GE executives – no surprise. They are all about socializing risk and privatizing profit and have been for at least the past 50 years.

I cannot admire their energy decision policies. I point back to the Beijing Olympic advertising campaigns – not a single one mentioned either the ESBWR or the ABWR, but there sure were a LOT of worthless (at least to customers and taxpayers) windmills.

I often wonder why many people don’t get very excited when they first hear that uranium has 2 million times more energy per unit of mass compared to fossil fuel. John Hofmeister is probably one of those folks.

Perhaps people think of the number 2 million as just another number, like $2 million dollars, or they can’t visualize what this ratio looks like. With the word ‘billion’ being bounced around on TV news all the time, maybe a million just doesn’t excite the way it used to. A million of any one object is enormous quantity that cannot easily be visualized by the average person. Studies have shown most people can only remember about 7 or 8 random objects shown to them for a brief period. The human mind doesn’t naturally grasp what a million of anything really is. Sure, we all know what number one million is, but having a true visualization of that quantity is the breakthrough that’s needed to create that awe inspiring wow-factor.

If that can be communicated then saying, “ok, now double it” should get an even bigger “wow” reaction. With impressive numbers like these, maybe we can’t easily blame those who don’t seem to get it, but realize that nuclear energy hasn’t done enough to sell itself at large with these very impressive figures.

Energy density is one issue, but the economics of bringing it to market are an entirely different concern. World Nuclear Association, a pro industry group, provides a careful look at power systems from the vantage point of usable energy, costs, and life-cycle analysis (which is really the only calculation that matters in comparing energy sources on an objective basis of energy conversion). What did they find? Coal and natural gas compares very well to nuclear (using diffusion enrichment techniques in an open cycle LWR). Hydro comes in on par with nuclear using more efficient centrifuge enrichment (one study suggests it beats out nuclear 4:1). Solar makes a modest showing, wind beats out nuclear in newer studies (comes out low in older studies). But assumptions play a large role in these calculations, they hold, as different sources vary in capacity factors, energy inputs, length of lifecycle, changing availability of fuel resource, etc., and we aren’t in the habit of comparing energy resources on this basis.

Add to this external costs

Mr. Hofmeister shares a characteristic of most CEOs of large corporations. Though they may be passionate about the products they provide, at the end of the day, they are more passionate about money. The products provided to the customer are simply the means to their real passion. Contrast this to the visionary minority of CEOs who often have come up through the ranks from the product side. At the end of the day, these CEOs have a passion for providing solutions to the customer with their products, and money is the means to attain their real passion.

The proof of this for the oil companies can be seen in how they regard themselves as oil companies, rather than energy companies.

John

I’m a big fan of Hofmeister

I think you’re being slightly unfair.

If you think of the product of the nuclear industry being electricity, that’s a commodity that hasn’t changed ever since they settled on 60 cycle AC. If you think of it as heat, there’s some possibility of getting it at a higher temperature or under dry conditions in the future, but the quality of the heat is going to say the same as long as we keep using LWRs.

Now, the real innovation in the nuclear industry in the last 30 years has been sustaining incremental innovation. Reliability, on-line percentage and fuel performance have gotten steadily better. Future reactors will be safer by a few orders of magnitude, and hopefully modular construction will lower costs and increase predictability, but the product is going to be the same.

The very success of the LWR is likely to suppress the development of other reactor types. When it’s plausible that the risk of (any) fuel damage can be reduced to the 10^7-10^8 reactor*year range in the LWR, the 10^6 range risk of a incident that totals an LMFBR core looks worse (even if the incident does no harm to the public)… And when you consider that any other reactor type will face growing pains as did the LWR, and that it takes a long time to really understand fuel performance, it looks tough for competitive reactors to move in.

Although the oil/gas industry keeps giving us the same old stuff, it’s working harder to get it. Although many people are concerned (myself included) about the risks of hydrofracking and deepwater drilling, both of these are serious innovations that provide access to a lot of “the same old stuff”. The same is true of the tar sands developments in Canada, a technology that may be diffused to other places.

Of course, the risk that comes with these new oil and production technologies gives us a reason to stop and think about safer alternatives.

Paul – the compaint is not that the oil companies are selling the same old product. There is nothing wrong with that. My issue is that the growth model is to keep selling about the same amount every year at an ever increasing price. Nuclear power plants – even without any new technology or construction have been able to increase their output and lower their costs rather steadily.

The other part of the issue is that the oil companies and the friends in OPEC would still have plenty of easy oil left if they had not worked so successfully with the antinuclear organizations for the past 40 years to suppress a viable replacement in many markets. The world could have been consuming 20-30 million barrels per day instead of 60-80.

Nuclear, by itself, doesn’t compete with oil in 2011. Perhaps it did in 1970 (when oil burning electricity plants were being turned off) and perhaps it will in 2025 (if and when electric cars become widespread) and perhaps it will in a distant future (2040?) when some technology is practical to produce liquid fuels from nuclear energy.

If we’d built the 500 or so LWRs that people were thinking of building in the 1970s, the markets for coal and natural gas would have taken a big hit, but I think people would still be putting gasoline in their cars. Even if electricity were free, that, in itself, wouldn’t drive the adoption of electric cars because the operating costs of electric cars are already drastically lower than gas cars… It comes down to the capital cost of the battery.

If oil depletion reaches crisis levels in the next few decades, the fastest way nuclear can help may be to displace the use of natural gas for electricity generation, freeing it up for use as a transportation fuel. (Unless we get that breakthrough in battery technology.)

@Paul – are you limiting your statement to the continental United States? World wide, there is still a fair quantity of oil being burned to produce electricity in power plants. It is also being burned to push ships around the ocean, an application that nuclear proved it was pretty good at starting in January 1955. The Northeast US still burns a lot of oil for space heating when cheap electric furnaces can do the job just as well. We have also been running a lot of electric powered trains for several decades, yet diesel fuel still propels a majority of the locomotives. Why?

I refuse to accept the idea that we need to wait for an unrecoverable crisis to recognize that we have a superior heat source that can do a lot of what oil does today. Necessity is the “mother of invention” except when it is not. The people who lived in the 12th century would have loved to have a reliable heat and power source, they really needed it, but somehow they never got around to inventing their way out of trouble.

Hey there guys, my name is Aaron and I hate to just chime in the middle of the discussion, but I think that Mr. Adams has hit really the heart of the issue in his last comment. The argument over the implementation of nuclear power has not been ended by the presentation of facts. I don’t think it ever can be since it is such a political issue. I am with Mr. Adams in hoping that we can all see the solution before we actually need to rely upon it, but I don’t know if that will happen. It looks like it could be necessity that we have to rely upon to end the debate. That seems to be the case now with the hole carbon sequestration debate. Politics sees it as necessary to help the fight against something much worse. This is really the only reason the nuclear industry is getting attention again. I don’t think it has much to do with it being a better power source.