Solar’s dirty secrets: How solar power hurts people and the planet

By Brian Gitt

Brian’s an energy entrepreneur, investor, and writer. He’s been pursuing truth in energy for over two decades. First, as executive director of a green building trade association. Then as CEO of an energy consulting firm (acquired by Frontier Energy) specializing in the commercialization of technology in buildings, vehicles, and power plants. And more recently he founded UtilityScore, a software startup, that estimated utility costs and savings for 100M+ homes and led business development at Reach Labs developing wireless power. Follow him on Twitter and check out his website.

False beliefs about renewable energy are harming the environment. I say this as someone who championed renewable energy for over two decades—first as executive director of a green building non-profit, then as CEO of a consulting firm specializing in clean energy, and most recently as founder of a cleantech startup. I thought my efforts were helping to protect the environment. But I was wrong.

Like many people, I believed the worst harm to the environment came from fossil fuels—and greedy companies exploiting the land, polluting the air, and destroying ecosystems to get them. It took me many years to realize that this viewpoint is distorted and to admit that many of my beliefs about renewable energy were false. And now I’m ready to talk about what we really need to do to save the environment.

The Truth about Energy

The truth is this: every source of energy has costs and benefits that have to be carefully weighed. Wind and solar are no different. Most people are familiar with the benefits of wind and solar: reduced air pollution, reduced greenhouse gas emissions, and reduced reliance on fossil fuels. But not as many recognize the costs of wind and solar or understand how those costs hurt both the environment and people—especially people with lower incomes.

Looking at Life Cycles

To fully evaluate how solar and wind energy hurt people and the environment, we must consider the lifecycle of renewable energy systems. Every artifact has a lifecycle that includes manufacture, installation, operation, maintenance, and disposal. Every stage in that lifecycle requires energy and materials, so we need to tally up the energy and materials used at every stage of the cycle to fully understand the environmental impact of an object.

Think of a car. To understand its full impact on the environment, we must consider more than simply how many miles it gets per gallon of gas. Gas consumption measures only the cost of operating the car, but it doesn’t measure all the energy and materials that go into manufacturing, transporting, maintaining, and ultimately disposing of the car. Tally up the costs at each stage of the car’s lifecycle to get a more complete picture of its environmental impact.

The same is true of solar panels. To fully understand the environmental impact of solar panels, we need to consider more than simply how much energy and emissions the panels produce during operation. We also need to tally up the expenditure of energy and materials that go into manufacturing, transporting, installing, maintaining, and ultimately disposing of the panels. Once we tally up those costs, we see that solar power leaves a larger ecological footprint than advocates like to admit.

The Environmental Costs of Manufacturing and Installing Solar

Solar advocates often gloss over the solar-panel manufacturing process. They just say, “We turn sand, glass, and metal into solar panels.” This oversimplification masks the real environmental costs of the manufacturing process.

Solar panels are manufactured using minerals, toxic chemicals, and fossil fuels. In fact, solar panels require 10 times the minerals to deliver the same quantity of energy as a natural gas plant.[1]Quartz, copper, silver, zinc, aluminum, and other rare earth minerals are mined with heavy diesel-powered machinery. In fact, 38% of the world’s industrial energy and 11% of total energy currently go into mining operations.[2]

Once the materials are mined, the quartz and other materials get melted down in electric-arc furnaces at temperatures over 3,450°F (1,900°C) to make silicon—the key ingredient in solar cells. The furnaces take an enormous amount of energy to operate, and that energy typically comes from fossil fuels.[3] Nearly 80% of solar cells are manufactured in China, for instance, where weak environmental regulations prevail and lower production costs are fueled by coal.[4]

There are also environmental costs to installing the panels. Solar panels are primarily installed in two ways: in solar farms and on rooftops. Most U.S. solar farms are sited in the southwestern U.S. where sunshine is abundant. The now-canceled Mormon Mesa project, for instance, was proposed for a site about 70 miles northeast of Las Vegas. It was slated to cover 14 square miles (the equivalent of 7,000 football fields) with upwards of a million solar panels, each 10-20 feet tall. It would have involved bulldozing plants and wildlife habitat on a massive scale to replace them with concrete and steel. Environmentalists and local community groups opposed the project because it threatened views of the landscape and endangered species like the desert tortoise, and the proposed project was eventually withdrawn.[5]

Placing massive solar farms far from populated areas presents additional challenges as their remote locations require new power lines to carry energy to people who use it. Environmentalists and local community groups often fiercely oppose the construction of ugly power lines, which also have to get approval from multiple regulatory agencies. Those factors make it almost impossible to build new transmission lines in the U.S.[6] If approval is granted, installing those lines takes a further toll on the environment.

In addition, the farther the electricity has to travel, the more energy is lost as heat in the transmission process. The cost-effective limit for electricity transmission is roughly 1,200 miles (1,930 kilometers.) So you can’t power New York or Chicago from solar energy farms in Arizona.

Limitations to Rooftop Solar

Rooftop solar installations could sidestep some of the problems of solar farms, but they have problems of their own.

First, many buildings are not suitable for rooftop solar panels. Rooftop installations are typically exposed to less direct sunlight due to local weather patterns, shade from surrounding trees, the orientation of a building (which are often not angled toward the sun), or the pitch of the roof.

Second, the average cost to buy and install rooftop solar panels on a home as of July 2021 is $20,474.[7] This makes rooftop installations cost-prohibitive—especially for lower-income families.

Finally, even if we installed solar panels on all suitable buildings in the U.S. we could generate only 39% of the electricity the country needs according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.[8]

Solar panels also have a shorter lifespan[9] than other power sources (about half as long as natural gas[10] and nuclear plants[11]), and they’re difficult and expensive to recycle because they’re made with toxic chemicals. When solar panels reach the end of their usable life, their fate will most likely be the same as most of our toxic electronic waste: They will be dumped in poorer nations. It is estimated that global solar panel waste will reach around 78 million metric tons by 2050[12]–the equivalent of throwing away nearly 60 million Honda Civic cars.[13]

The Human Costs of Solar

Solar harms more than the environment; it hurts people—especially the economically disadvantaged, who face a hard choice between paying high energy costs or suffering energy poverty.

Consider a family of four in California’s Central Valley. They currently pay one of the highest rates for electricity in the U.S.—80% more than the national average.[14] They may be forced to choose between paying for daycare or turning off their air conditioner in 100-degree heat. Families like this are not rare. The California Public Utilities Commission says 3.3 million residential customers have past-due utility bills. Taken together they owe $1.2 billion.[15]

Adding more renewable energy to the grid is not only expensive; it’s dangerous! The North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC), a nonprofit organization that monitors the reliability, resilience, and security of the grid, says that the number-one risk to the electrical grid in America is adding more unreliable renewables.[16]

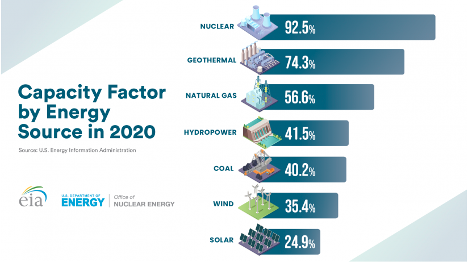

The reliability of a power source is measured by capacity factor. The capacity factor of a power plant tracks the time it’s producing maximum power throughout the year. When we compare the capacity factors of power plants, we see that solar is the least reliable energy source: natural gas is twice as reliable as solar, and nuclear energy is three times more reliable.

Recent events in Texas and California highlight the risk of adding more unreliable power sources to the grid. The blackouts were caused by several interconnected factors. The Texas power blackout in February 2021 left 4.5 million homes and businesses without power (some for several days) and killed hundreds of people.[17] The immediate trigger of the Texas blackout was an extreme winter storm, but that storm had such a massive effect because of factors rooted in poorly designed economic incentives. Texas wind and solar projects collected $22 billion in Federal and State subsidies.[18] These subsidies distorted the price of power and hence compromised the reliability of the Texas grid. The electricity market is complex. And multiple factors converged to cause the blackout including a failure of government oversight and regulation. But if investments had flowed to natural gas and nuclear power plants instead of unreliable solar and wind, the blackout would likely have lasted minutes instead of days.

Unreliable solar and wind power were also among the three primary factors causing California’s rolling blackouts in August 2020, according to the State of California’s final report on the power outages.[19]

A year later, in July 2021, Governor Gavin Newsom declared a state of emergency and authorized the use of diesel generators to overcome energy shortfalls. And in August 2021, the state announced the emergency construction of five new gas-fueled generators to avoid future blackouts.[20]

Events in California and Texas highlight another unappreciated cost of solar and wind: Compensating for their unreliability requires the use of more reliable sources of power, namely fossil fuels. A study conducted across 26 countries over two decades by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) concluded for every 1 megawatt of solar or wind power installed there need to be 1.12 megawatts of fossil fuels (usually natural gas) as backup capacity because solar and wind are unreliable.[21] Moreover, using backup diesel generators and ramping power plants up and down to meet energy shortfalls are two of the worst ways to use fossil fuels; they’re inefficient and cause unnecessary pollution.

A final point: solar and wind have low power densities. According to a facts guide on nuclear energy from the U.S. Department of Energy, a typical 1,000-megawatt nuclear facility in the United States needs a little more than 1 square mile to operate. Solar farms, by contrast, need 75 times more land and wind farms need 360 times more land, to produce the same amount of electricity.[22]

Even if we could overcome all the practical constraints on storing, transmitting, and distributing solar power, supplying a country the size of the U.S. would require over 22,000 square miles of solar panels[23]—approximately the size of New Jersey, Maryland, and Massachusetts combined.[24] And the unreliability of solar power means that even with that many solar panels, we would continue to need most of our existing power plants.

The Costs of Energy Poverty Worldwide

The less-measured costs of promoting renewable energy extend far beyond California and even the United States. Energy is the foundation of civilization. Access to it enables healthcare, education, and economic opportunity. It liberates men from dangerous jobs, women from domestic drudgery, children from forced labor, and animals from backbreaking work.

Energy poverty, by contrast, leads to malnutrition, preventable disease, lack of access to safe drinking water, and contributes to 10 million premature deaths per year.[25] Over 3 billion people—40% of the Earth’s population—live in energy poverty. Nearly one billion people don’t have access to electricity and use wood or animal dung for cooking and heating their homes.[26] Another billion only get enough electricity to power a light bulb for a few hours a day.[27] Women in energy poverty spend more than two hours a day gathering water[28]for drinking and wood for cooking.[29] And over 3.8 million people die every year[30] from breathing wood smoke while cooking—something which could be prevented by using stoves fueled with propane or butane.

You might think that wealthy nations with a commitment to human rights would take steps to alleviate energy poverty. But exactly the opposite is happening: Wealthy nations are pulling up the ladder behind them and subjecting the developing world to energy poverty.

In 2019, the European Investment Bank announced it would stop financing fossil fuel power plants in poor nations by 2021.[31] And the World Bank (the largest financier of developing nations) is developing a similar policy.[32] The hypocrisy is mind-boggling: wealthy nations get 80% of their energy from fossil fuels and reap the benefits of unprecedented prosperity due to the low-cost, reliable energy they provide.[33]

Weighing the Costs and Benefits

Evaluating the environmental impact of solar panels simply in terms of the CO2 emissions of operating solar panels is like evaluating the environmental impact of a car simply in terms of how many miles it can travel on a gallon of gas. It’s an overly simplistic view that fails to account for all the environmental costs of mining, manufacturing, installing, operating, and disposing of the solar panels.

Once we tally up all of solar’s lifecycle costs, it’s no longer obvious that solar is better for the environment than other sources of energy, including highly efficient natural gas. In fact, solar energy might be worse for the environment after we factor in its unreliability. California’s recent energy crisis illustrates that new solar installations need to be coupled with more reliable sources of power–like natural gas plants–to compensate for their unreliability.

That unreliability is not something that better technology can erase. It’s simply due to the very nature of solar power: the sun doesn’t shine 24 hours a day, so it’s impossible for solar panels to produce electricity 24 hours a day.

Some people theorize that we will eventually be able to store surplus solar energy in batteries, but the reality is batteries cost about 200 times more than the cost of natural gas to solve energy storage at scale.[34] In addition, batteries don’t have enough storage capacity to meet our energy needs. Currently, America has 1 gigawatt of large-scale battery storage that can deliver power for up to four hours without a recharge. A gigawatt is enough energy to power 750,000 homes, which is a small fraction of the amount of energy storage we would need for a grid powered mostly by renewables. It is, for instance, less than 1% of the 120 gigawatts of energy storage that would be needed for a grid powered 80% by renewables.[35]

Manufacturing batteries also takes a serious toll on the environment, as they require lots of mining, hydrocarbons, and electricity. According to analysis completed by the Manhattan Institute, it requires the energy equivalent of about 100 barrels of oil to make batteries that can store a single barrel of oil-equivalent energy. And between 50 to 100 pounds of various materials are mined, moved, and processed for one pound of battery produced. Enormous quantities of lithium, copper, nickel, graphite, rare earth elements, and cobalt would need to be mined in China, Russia, Congo, Chile, and Argentina where weak environmental regulations and poor labor conditions prevail.[36]

The high cost and poor performance of batteries explain why there’s no market for long-duration (eight or more hours) battery storage. Existing battery technology is unlikely to overcome the limits of physics and chemistry in the next decade to come anywhere close to the levels of efficiency we need to store energy at scale.

So adding solar power to the grid will not eliminate the need for natural gas. And when you really examine the harm that solar installations do to the environment, solar begins to look worse for the environment on balance than efficient natural gas plants.

When we add the human costs to the tally, the case for solar looks even worse. Forcing low-income people to pay 80% more for electricity in places like California is ethically dubious and increases wealth inequality. And these are just the costs in developed countries. When we consider the human costs of energy poverty worldwide, using solar to decrease CO2 emissions subjects poor people to unnecessary suffering without substantially reducing climate risk.

Real Benefits of Solar

If you have read this far, you might believe I think solar energy is bad. Nothing could be further from the truth. I think solar is a great technology, but it just doesn’t scale well. When it’s limited to its original applications, it can be a game-changer for many people. Think of African villages that get a lot of sun but are too remote to justify the cost for building new power lines. Equipping a school, community center, or individual homes with solar panels could be a game-changer and lift many people out of energy poverty.

These are the applications for solar that we should be looking into. But it is wrongheaded to see solar as a replacement for more reliable sources of energy in industrialized, power-hungry nations. That’s an illusion.

But that illusion does make people in developed countries feel good about themselves because it makes them feel less guilty about a lifestyle based on excessive energy consumption. They want to drive nice cars, live in big homes, vacation in exotic destinations, and enjoy all the conveniences of modern life–without worrying that they are hurting poor people and or the planet.

I’m not pointing fingers. I put myself in this category. It took me years to see that my reasons for pushing solar and wind power were false. I liked seeing myself as a hero defending the environment against ruthless pillagers, and because I wanted other people to see me this way. My false ideas about fossil fuels and renewables were as bound up with my sense of identity and self-worth as they were with my lifestyle.

But I now understand that I was using those ideas as moral camouflage, and I was able to maintain them only by remaining ignorant about the real costs and benefits of different energy sources. That ignorance prevented me from making a real difference.

I’ve dedicated most of my life to protecting the environment. But for years, I was going about it in the wrong way. I thought I was acting morally and protecting the well-being of people and the planet. But in fact, I was harming both, and I see people making the same mistakes today. Governments, companies, and building owners around the world invested $2.7 trillion on renewable energy between 2010-2019, and they plan on investing an additional $1 trillion by 2030.[37] We can make better investment decisions to maximize human flourishing and minimize environmental harm.

What We Need To Do

My message probably stands in contrast to most of what you’ve been told about renewable energy. But I’m convinced that the stakes are too high for me to sit back and not to challenge the false beliefs that continue to fuel poor investments and bad policy decisions. It’s time to stop virtue signaling and take off our moral camouflage so we can meet the problems of climate change and energy poverty head-on.

If we’re serious about tackling climate change, protecting the environment, and helping impoverished people around the world, we need to stop chasing fantasies about solar and wind energy. We need to start weighing all the costs and benefits of all energy sources—wind, solar, natural gas, coal, hydro, geothermal, and nuclear.

Here are five steps we can begin to take towards making things better for both people and the planet:

- End subsidies and incentives for solar and wind power;

- Invest in research and development to advance new energy technologies;

- Build new efficient natural gas power plants (and hydro and geothermal where possible);

- Reform regulations and build nuclear power plants;

- Retire the worst coal power plants (5% of power plants create 73% of carbon emissions from electricity generation)[38].

Every day we spend chasing fantasies causes unnecessary harm and suffering. Let’s pursue energy solutions that benefit people and also save the environment.

[1]U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), “Quadrennial Technology Review: An Assessment of Energy Technologies and Research Opportunities” September 2015, page 390https://www.energy.gov/quadrennial-technology-review-2015

[2] J.J.S. Guilbaud, “Hybrid Renewable Power Systems for the Mining Industry: System Costs, Reliability Costs, and Portfolio Cost Risks” University College London, 2016, https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1528681/

[3] Stephen Maldonado, “The Importance of New “Sand-to-Silicon” Processes for the Rapid Future Increase of Photovoltaics” October 2020, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsenergylett.0c02100

[4] Kenneth Rapoza, “How China’s Solar Industry Is Set Up To Be The New Green OPEC” Forbes.com, March 2021, https://www.forbes.com/sites/kenrapoza/2021/03/14/how-chinas-solar-industry-is-set-up-to-be-the-new-green-opec/?sh=1355297a1446

[5] AP News, “Plans for largest US solar field north of Vegas scrapped” APnews.com, July 2021

[6] Robinson Meyer, “Unfortunately, I Care About Power Lines Now” The Atlantic, July 2021,

[7] Jacob Marsh, “The cost of solar panels in 2021: what price for solar can you expect?” EnergySage.com, July 2021, https://news.energysage.com/how-much-does-the-average-solar-panel-installation-cost-in-the-u-s/

[8] Pieter Gagnon, Robert Margolis, Jennifer Melius, Caleb Phillips, and Ryan Elmore, “Rooftop Solar Photovoltaic Technical Potential in the United States: A Detailed Assessment” National Renewable Energy Laboratory, January 2016, https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy16osti/65298.pdf

[9] The Solar Technical Assistance Team (STAT), STAT FAQs Part 2: Lifetime of PV, National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), April 2018, https://www.nrel.gov/state-local-tribal/blog/posts/stat-faqs-part2-lifetime-of-pv-panels.html

[10]S&P Global Market Intelligence, “Average age of US power plant fleet flat for 4th-straight year in 2018” January 2019 https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/trending/gfjqeFt8GTPYNK4WX57z9g2

[11] Energy.gov, Office of Nuclear Energy, “What’s the Lifespan for a Nuclear Reactor? Much Longer Than You Might Think” May 2021 https://www.energy.gov/ne/articles/whats-lifespan-nuclear-reactor-much-longer-you-might-think

[12] International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), “End-of-Life Management Solar Voltaic Panels” 2016 https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2016/IRENA_IEAPVPS_End-of-Life_Solar_PV_Panels_2016.pdf

[13] “Honda Civic Features And Specs, Weight Information, 2021” CarandDriver.com, https://www.caranddriver.com/honda/civic/specs

[14]Laurence du Sault, “Here’s why your electricity prices are high and soaring” Calmatters.org, March 2021, https://calmatters.org/california-divide/debt/2021/03/california-high-electricity-prices/

[15] California Public Utilities Commission, “Energy Customer Arrears 2020 Status Update and New Order Instituting Rulemaking, January 2021 https://www.scribd.com/document/495707616/Residential-Energy-Customer-2020-Arrears-Presentation-for-Voting-Meeting-Update-Jan-2021

[16] Reliability Issues Steering Committee, North American Electric Reliability Corporation, Ranking of Identified Risks, page 49, January 2021, https://www.nerc.com/comm/RISC/Agenda%20Highlights%20and%20Minutes/RISC_Meeting_Agenda_Package_Jan_28_2021_PUBLIC.pdf#search=reliability%20risk%20ran

[17]Peter Aldhous, Stephanie M. Lee, Zahra Hirji, “The Texas Winter Storm And Power Outages Killed Hundreds More People Than The State Says” BuzzFeed News, May 2021 https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/peteraldhous/texas-winter-storm-power-outage-death-toll

[18] Robert Bryce, “The Texas blackouts were caused by an epic government failure” The Dallas Morning News, August 2021, https://www.dallasnews.com/opinion/commentary/2021/08/01/the-texas-blackouts-were-caused-by-an-epic-government-failure/

[19] California ISO, “Final Root Cause Analysis Mid-August 2020 Extreme Heat Wave” January 2021 http://www.caiso.com/Documents/Final-Root-Cause-Analysis-Mid-August-2020-Extreme-Heat-Wave.pdf

[20] Mark Chediak and Naureen S Malik, “California to Build Temporary Gas Plants to Avoid Blackouts” Bloomberg.com, August 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-08-19/california-to-build-temporary-gas-plants-to-avoid-blackouts

[21] Elena Verdolini, Francesco Vona, and David Popp, “Bridging the Gap: Do Fast Reacting Fossil Technologies Facilitate Renewable Energy Diffusion?” National Bureau of Economic Research, July 2016 https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w22454/w22454.pdf

[22] Energy.gov, Office of Nuclear Energy, “The Ultimate Fast Facts Guide To Nuclear Energy” January 2019, https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2019/01/f58/Ultimate%20Fast%20Facts%20Guide-PRINT.pdf

[23] Energy.gov, Solar Technologies Energy Office, “Solar Energy in the United States” September 2021, https://www.energy.gov/eere/solar/solar-energy-united-states

[24] StateSymbolsUSA.org, “States by Size in Square Miles” https://statesymbolsusa.org/symbol-official-item/national-us/uncategorized/states-size

[25] World Health Organization (WHO), “Health Topics” https://www.who.int/health-topics

[26] The World Bank, “Energy Overview” https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/energy/overview

[27] Todd Moss, “Ending global energy poverty – how can we do better?” World Economic Forum, November 2019, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/11/energy-poverty-africa-sdg7/

[28] “UNICEF: Collecting water is often a colossal waste of time for women and girls” Unicef.org, August 2016, https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/unicef-collecting-water-often-colossal-waste-time-women-and-girls

[29]“ ENERGIA, World Bank—Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP) and UN

Women, United Nations, Policy Brief #12 Global Progress of SDG 7— Energy and Gender” 2018, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/17489PB12.pdf

[30] World Health Organization (WHO), “Household Air Pollution” 2021, https://www.who.int/health-topics/air-pollution#tab=tab_3

[31] BBC.com, “European Investment Bank drops fossil fuel funding” November 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-50427873

[32] Bernice von Bronkhorst, “Transitions at the Heart of the Climate Challenge” The World Bank, May 2021, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2021/05/24/transitions-at-the-heart-of-the-climate-challenge

[33] Robert Rapier, “Fossil Fuels Still Supply 84 Percent Of World Energy — And Other Eye Openers From BP’s Annual Review” Forbes.com, June 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/rrapier/2020/06/20/bp-review-new-highs-in-global-energy-consumption-and-carbon-emissions-in-2019/?sh=1dbd154666a1

[34] Mark P. Mills, “The New Energy Economy: An Exercise in Magical Thinking” Manhattan Institute, March 2019, https://www.manhattan-institute.org/green-energy-revolution-near-impossible

[35] National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), “Renewable Electricity Futures Study” 2012, https://www.nrel.gov/analysis/re-futures.html

[36] Mark P. Mills, “The New Energy Economy: An Exercise in Magical Thinking” Manhattan Institute, March 2019, https://www.manhattan-institute.org/green-energy-revolution-near-impossible

[37] United Nations Environment Programme with Frankfurt School & Bloomberg NEF, “Global Trends in Renewable Energy Investment 2020”, Key Findings, 2020, https://www.fs-unep-centre.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/GTR_2020.pdf

[38] Alex Fox, “Just 5 Percent of Power Plants Release 73 Percent of Global Electricity Production Emissions” Smithsonian Magazine, August 2021, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/five-percent-power-plants-release-73-percent-global-electricity-production-emissions-180978355/

Good article. I like the pragmatic approach the author takes at the end. “Do what makes sense.”

Thanks for the well-researched (and referenced) article Brian. It’s lengthy; I’ll try to get to it this weekend.

Just one thing, the footnote links in the document go to Brian’s site and not to the footnotes in this page.

@Engineer-Poet

Thank you for the important information. I count on you for careful reading and feedback. We are working to correct the issue. It’s not quite as simple as I thought it would be, but we should have the references working right in a day or so.

For many years I made my living nit-picking the finest details in code, in drawings and in specifications. Old habits die hard and as long as I have them I’ll try to put them to good use.

Natural gas electric power plants retrofitted to use renewable methanol will probably be the primary means of electricity production in the US by the year 2050, IMO. And the cryocapture of CO2 from such electric power facilities could be used to produce more methanol from the synthesis of CO2 with nuclear produced hydrogen.

Land based and ocean based nuclear power plants will probably be the primary means of producing carbon neutral methanol.

Since carbon neutral methanol is likely to be significantly more expensive than natural gas derived from fossil fuels, electricity from solar power plants could be utilized to reduce eMethanol demand by perhaps 10 to 25% depending on the region of the country.

Solar energy currently represents less than 1% of the total energy consumed in the US. So I doubt that solar energy consumption in the US will ever represent more than 10% of the energy consumed in the US this century century.

Brian wrote:

“The reliability of a power source is measured by capacity factor. The capacity factor of a power plant tracks the time it’s producing maximum power throughout the year.”

I’m not sure I agree with either of those statements. Capacity factor Cf is simply the ratio of the energy a plant (or plants) generate over the course of a year, divided by the energy those plants could have generated if they had generated at maximum capacity at every minute of the year. That is all. In whatever context Levelized Cost of Energy is a meaningful metric, then Cf is a useful (and required) input. But it shouldn’t be confused with reliability.

Take a random collection of 10 open-cycle gas peaker plants, with thermal effiency during their hours of wildly variable operation of maybe 20 – 30 percent. This is half or third that of a constant load combiined cycle plant, and twice the fuel cost. Naturally, a Balancing Authority will schedule peaker plants only when it really needs them; their resulting Cf is a desultory 10%.

https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/pdf/electricity_generation.pdf (10%, for new construction)

https://www.cleanegroup.org/ceg-projects/phase-out-peakers/ (4%, current)

But when the BA does really need those peaker plants, it generally needs them really bad. Fortunately, open cycle peakers are simple and reliable. The BA can count on 8 of those 10 peakers to be available when it needs them.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Availability_factor

Big dam hydro is similar. Their turbines are usually spec’ed in considerable excess of average river flow to provide peaking service. Their Cf suffers as result: Hoover Dam’s Cf is 23%, whereas nearby Agua Caliente Solar Project is 29%. Notwithstanding cloudy weeks or extended drought, which is the more reliable?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capacity_factor#Hydroelectric_dam

” then Cf is a useful (and required) input. But it shouldn’t be confused with reliability.”

Strange opinion. Appears you do not work at a commercial electrical power plant. The Nuclear Plant Manager I worked for took a job as the Site Manager for a three unit, fairly new, mine-mouth Coal fired power facility. His major reason for this promotion was that each of the plant at that facility had a “less then Steller” capacity factor < 50%, and the performance record he had at the NPP. He immediately recognized that the attitude at the plant was "If it isn't Broke don't Fix It." Basically, they did not perform any type of Preventive Maintenance. When it broke, they fixed it – that meant they had an outage and were not making electricity and probably paying twice as much to by the replacement electricity. I spent a month or so at the station looking at their process and on one inspection of the equipment I opened up the enclosure for the position controller for a major feed-water flow valve. The enclosure, an 8" X 8" X 4," box was almost 1/2 full of coal dust as fine as talcum powder. If any fuller it would have interfered with the mechanical action in the enclosure. Equipment operators usually carried a kitchen broom in front of them waving it up and down as they walked the rout of less used pathways in areas where there is High Pressure Steam. They did this to be sure that there were no leaks from the high pressure, 3,000 PSI steam as a steam jet is invisible and could cut off an arm if the walked through it. After implementing a "Preventative Maintenance Program"(PMP) within 2 years the number of unexpected outages fell to less than two total for the station per year instead of over six per year per plant. Within a few years many other Coal plants were also implementing a PMP at their plant. I also provided consulting service to a "Sister" NPP that had a less than 50% CF for the exact same reasons. After implementing a PMP their CF went up to the mid 80's. That is why management looks at a plants CF number. It is a good indicator of readiness and reliability.

I agree with Ed. But then I’m only a senior engineer at a working geothemal plant that has had a capacity factor of over 90% for 40 years – we got to 100% one year when we had no scheduled surveys and could overdrive in the winter. The figure quoted in the lead post is distorted by Geysers where it was overbuilt in the boom and bust days and now run as a two shifter. The plants in Nevada are a lot better indicators.

If the plants are on must-run dispatch, then capacity factor is an indicator of reliability. It is not synonymous. In geothermal binary plants for example, the MW go up and down a lot because of the air temperature which is the heat sink. This is when the steam or brine coming into the plant has the same massflow and enthalpy. For one of ours that is rated at 16MW gross, it can vary between 12 and 20MW (the generator rating). Just a practical example of Thermodynamics first law. By second law exergy analysis, the efficiency doesn’t significantly change.

For a plant that is only dispatched on an as-needed basis (or two-shifted) the capacity factor is a very poor indicator of reliability. That is what Ed is pointing out. In those cases there, then availability and forced outage factor are the relevant indicators. The real thing for a power network is how well the station meets its dispatch. It doesn’t matter if it can only run 2 hours a day. If it meets what it says it will do every day and no trips, that can be accommodated. The schedule is the important thing.

Nuclear and most geothermal are great at baseload, thermal steamers and CCGTs best at two shifting and OCGTs for peaking. Solar and wind are useless at meeting any dispatch, even on a two hour ahead schedule. A cloud goes over and solar plummets, then you have to ramp up OCGTs really quickly. That is what recently happened in Brisbane.

Slightly tangential to the topic, but the methods of making solar less unreliable can also be used to make baseload nuclear supply peaking power.

So e.g. molten salt storage stores energy in a molten salt. But solar thermal needs seasonal storage for reliability, and this only gives you intra-day-storage and is often still supplemented with gas for cloudy days etc. It’s just not a good fit.

For a high temperature reactor it just immediately makes a lot more sense. You’re making thermal energy anyway so there is no conversion loss, you’re just diverting heat. You’re only storing it intraday anyway so you’re only losing a couple of percent to the environment. You can store a few hundred kWh thermal per cubic metre in cheap salt. If you’re trying to do multi-week or seasonal storage that’s kind of bad, with losses of a few percent per day being especially horrid. But for supplying peak load, maybe 2000 W/person during 4 hours peak each day (and absorbing half that during the nightly lul during 8 hours). This is really a lot since you’re cycling each day reliably. Just back of the envelope the peak for mutliple households can be met with 1 cubic meter of cheap salt in an insulated basin.

If you have the high temperature reactor, most of proposed designs can load follow a bit anyway, but pumping out full power 24/7 and storing thermal energy in cheap salt offpeak might make even more sense as it buffers and supplies more power during the expensive peak hours, and if it is a dedicated “nuclear peaker plant” it can theoretically heat salt for 20 hours out of the day and dump that all on the grid during peak load. The extra cost besides the salt storage are on the steam plant (non-nuclear) side.

TerraPower Natrium and Moltex Stable Salt reactor designs both incorporate thermal salt storage. TerraPower is planning a demonstration plant in Wyoming. Moltex has completed its Vendor Design Review stage 1 for a plant in New Brunswick.

https://www.energy.gov/ne/articles/next-gen-nuclear-plant-and-jobs-are-coming-wyoming

https://www.moltexenergy.com/our-first-reactor/

@RichLentz. I agree. Both that I do not work at a commercial electrical power plant, and also that you are making a direct apples-to-apples comparison within a restricted class of thermal plants. In this case similar — or even the same — coal plants operating under similar market and demand conditions.

That is not what the author was doing comparing overall average capacity factors of wildly disparate generator types operating under different market rules. I gave specific examples where comparing such capacity factors might not be a reliable indicator of reliability.

I also commend your own experience and work supplying us all with reliable electric power.

Thanks!

@Ed Leaver, You are very Welcome.

I also very much Agree with the author of this article. I am very much against the destructive impact the renewables’ have on the Environment. Especially because it is very unreliable.

The NPP I recently retired from has shut down as it is “Not competitive” with renewables’ and the board controlling the plant [in my opinion] want the service area to have more renewable’s. They have used this as a selling point to attract several big tech companies that brag about being 100% Renewable. However, since they shut down the plant and replaced that power with “Contracted” Wind Turbine power from an “Investor owned/operated Co.” that has replaced the power lost by shutting down a plant with a CF in the low 90’s we have experienced (on average) at least an outage every month. At least once a year my home experiences an outage that begins with 4 to 6 momentary loses of power be for the power is lost for well over an hour. Two of those multiply surge/loss cycles has required me to buy a new TV. Another required replacement of the freezer. That is what reliability prevents. At least the Heat-Pump has a protective loss of power delay.

Good article. The facts aside, it is a good illustration of how important it is to subject one’s convictions to opposing views to help understand just how well such convictions hold up. It seems that over recent years there has been an increasing number of renewables advocates realizing that their convictions and wishful thinking simply do not pass the mustard.