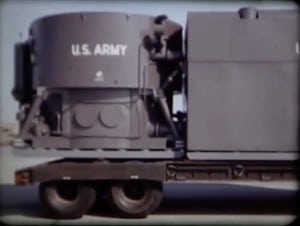

Using portable nuclear generators to break petroleum logistical dependence circa 1963

Note: The initial version of this post was written based on an incorrect interpretation of the Roman numeral date stamp at the end of the video. The film was made in 1963, not 1968. The post was revised after a commenter provided the correct production date. End note.

I have a theory about why the Environmental Movement transitioned from a 1950s and early 1960s position favoring nuclear energy as an alternative to burning hydrocarbons and building hydroelectric dams to an almost universally antinuclear position before the Arab Oil Embargo of October 1973. The below video illustrates some of the hope and visions developed during The Atomic Age.

I believe that some people who saw the video or were exposed to its themes in other venues recognized that their positions of wealth and power were threatened by rapidly improving atomic energy innovations.

Some might have been especially worried about inventions designed to solve military logistical challenges, knowing that machines refined by the military often find useful civilian applications. Hugely profitable markets would shrink dramatically if atomic energy lived up to its technical promise. Hydrocarbon industry leaders knew they would not have much success convincing people to abandon nuclear energy in order to enable wealthy interests to keep making profits by selling fossil fuels, so they undertook a more devious propaganda effort.

I believe they decided to obtain assistance from the increasingly popular Environmental Movement.

For example, in the early 1960s, the Sierra Club sustained a campaign known as “Atoms, Not Dams.” Their message was that nuclear power plants did not produce air pollution and did not require filling scenic, wildlife-filled valleys with with water.

As the 60s progressed the Club experienced a lengthy period of infighting about its support of — or opposition to — various energy sources. The board also struggled with decisions about the role of corporate contributions. By 1973 or 1974, the Sierra Club had settled on a strongly antinuclear energy position.

The discussions didn’t move fast enough for David Brower, a prominent Sierra Club leader. In 1969, he left the Club and used an initial investment of $200 K from Robert Anderson, the CEO of ARCO, to create Friends of the Earth (FOE) as a more militant antinuclear group.

My guess is that it was not hard to convince professional activists to turn their efforts to fighting nuclear energy. The persuasion was made easier by the close associations between nuclear energy and the military, even when the specific use of nuclear energy under discussion was reducing the logistical burdens of supplying electrical or motive power, not producing enormously destructive weapons.

The optimistically futuristic video about portable atomic generators included above was produced by the U.S. Army, an agency with a poor reputation among antiwar activists. The leaders of the antiwar movement gained useful experience as professional organizers and movement creators; they were so successful in attracting political support for ending the war that the U.S. left Vietnam in 1973.

Their animosity towards the military provided a means for far-sighted hydrocarbon strategists like Anderson to subtlety direct them and their organizations to actions aimed at slowing the development of atomic energy as a formidable alternative to their lucrative hydrocarbon economy.

Just imagine how different our world might be if the star of the above show, the Army’s ML-1, a truck-mounted 300-500 kwe nuclear heated, direct cycle, nitrogen cooled generator had been deployed, refined and improved during the five decades that have elapsed since it was first built and tested.

Adams EnginesTM

Many of you know that I spent a couple of decades working on an improvement to the basic concept of the ML-1 that I immodestly named the Adams Engine.

That effort was inspired by some dusty documents about the ML-1 and related projects that I discovered in the bowels of the Nimitz Library at the US Naval Academy in 1991.

The discovery happened soon after I had completed a tour as the Engineer Officer of a nuclear submarine that used a traditional pressurized water reactor/saturated steam system.

Though a series of influences, I became intrigued by the potential of combining an atomic fission heat source with a Brayton Cycle gas turbine using the same operating conditions as found in combustion gas turbines.

Some of the inspiration for that idea was born on frequent runs from Monterey to Pacific Grove with Mike LeFever while we were both students at the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School between 1985-1987, just before my Engineer tour. Mike and I engaged in good natured chatter during those runs. He had been the Chief Engineer on a gas turbine powered destroyer; I had just completed a junior officer tour on the USS Stonewall Jackson and was completely enamored with the capabilities nuclear energy provides.

Mike was just as enthusiastic about his experiences with gas turbines and convinced me that they were well suited for lazy, work-averse people like me when compared to a steam plant. The operational simplicity and ease of maintenance were music to my ears. The attraction of those features of gas turbines was especially clear after my 40-month tour as the Engineer on a 25-28 year old sub.

When I was assigned to the U.S. Naval Academy for shore duty, I took advantage of the opportunity to audit some higher level engineering classes focused on energy production. It’s not a frequently-seized benefit, but staff members are allowed to take classes as long as there are seats available.

Before the fall semester began, I met with Professor Mark Harper and explained that I wanted to take his energy conversion course seriously, completing all of the homework and paper assignments. With that entering commitment, he welcomed me into the class. The final project for the class was a paper on a chosen energy system.

My research began with entering the following Boolean search — “Nuclear AND gas turbine” into the computerized card catalog that the Nimitz Library had recently installed. The search produced a number of hits and fundamentally altered my life’s journey. I audited two 400 level alternative energy engineering courses taught by Dr. Chih Wu and then completed an independent research project [p. 29] that resulted in a published paper.

By early 1993 I had completed the work necessary to submit a patent application for the control system for a closed cycle gas turbine. Without accepting advice from others, I decided that I would resign my active duty commission, move my young family to Florida, start Adams Atomic Engines, Inc. and take the energy industry by storm.

It was a very rash and poorly laid out plan. My excuse is that I was young and possibly hypnotized by stories from Fast Company and the booming dot com era.

AAE Inc. didn’t work out as planned, though the control system patent was awarded in May 1994, even more promptly than expected. However, there were more than a few rocks in the road; we made some rather large detours as a family; my resulting career path included some unique features but the overall results of the subsequent decisions have turned out reasonably well.

My children and my wife still seem to like me and have forgiven — if not forgotten — the tough times. I don’t think I’ve lost too many friends; even those who lost the money they invested still take and return my phone calls.

All that history came flashing back a month or so ago when I came across the above video starring the ML-1.

Despite my dedicated research efforts, I had never seen it before. Somehow, the scenes of the ML-1 system in motion and being loaded onto a cargo plane made the lost opportunities seem much more real.

I remain convinced that the fission gas turbine is an attractive way to use an emission free, compact, low priced fuel with a simple power conversion system. The combination should result in zero emissions, long refueling intervals, passive safety, moderate capital costs, extreme simplicity, compact size and reasonable system weight.

Whenever people tell me that atomic fission is too expensive and slow to consider as a solution for big challenges like climate change, potable water scarcity, transportation dependence on liquid fuels, or international interventions aimed at protecting multinational petroleum corporations, I think about the little atomic engine that could address all of those issues if manufactured in series and distributed around the world.

One more thing – my patent on the control system has lapsed and entered the public domain about a decade ago. There is nothing stopping others from picking up the development. A couple of people have suggested that one explanation for a lack of interest is the fact that there is not much about the system that can be patented and monopolized.

Although I like the concept of these small reactors……

Gawd forbid the army gets an inventory of them, considering the history of their ability to be responsible stewards of the environment. Their idea of hazardous material disposal is “out of sight, out of mind”. Either dump it in the ocean, or dig a hole. And how many would we simply abandon to the “enemy” when we turn tail and run from one of our disastrous military misadventures?

The date at the end of the film is 1963, not 1969.

The irony is that fuel is an ever-more-costly part of military operations, and advances like custom zeolite absorbers appear to make it feasible to harvest CO2 from the atmosphere to produce hydrocarbon fuels… yet the military’s nuclear program is AFAIK dead outside the Navy.

Gone perhaps, but not forgotten: google “army small modular reactor”. One recent hit was taken here.

OMG!!!! Don’t let Ioannes see that link, he’ll have a stroke!

It certainly does seem strange that the promise of the film was totally unfulfilled. Makes me wonder whether some other country not controlled by fossil fuel and environmental folks can pick up this ball and run with it. The science is largely public domain. The expiration of the patent is one example.

“I remain convinced that the fission gas turbine is an attractive way to use an emission free, compact, low priced fuel with a simple power conversion system. The combination should result in zero emissions, long refueling intervals, passive safety, moderate capital costs, extreme simplicity, compact size and reasonable system weight.”

I agreed back when I first read your articles about this, and I still agree today.

The concept of reliable, portable nuclear power seems too good to ignore. One imagines that such reactors are installed in developing countries in remote locations instead of the conventional alternative: diesel gensets. Then, when the grid finally arrives at such locations, the atomic engine can be picked up and moved further downrange to await the arrival of the grid once more.

In this era where greenhouse gas emissions are increasingly coming from developing countries desperate to increase electricity access as quickly and cheaply as possible, it seems obvious that this kind of compact, portable, emission-free technology has an essential and bona fide role to play. Therefore I continue to think that sooner or later the Adams Engine – or something similar – will become a commercial reality. There are indications that it will.

That would work only in developing countries where the political environment is stable. You don’t want small reactors around in countries where there is a lot of sabotage activity. Those countries that have active guerilla warfare would be a bad choice because assets like power generation and transmission are usually the first targets of those groups.

On the other hand, there is a general trend to increasing political stability with increasing access to electricity. It’s not by any means universally valid, but as a broad generalization I think it holds water.

Rod,

Other than this video, do you have any of the other history of the ML-1? Were more than 1 ever made? Did any ever get used in military service? At what point did the Army decide they “didn’t need” it? Who was involved in the decision within either DoD, the Administration, or Congress to not fund this program? I think that would be interesting stuff to know.

I don’t know if any of that info is even still available, but because it’s been so long, perhaps some of that information could be obtained through FOIA requests?

@Jeff S

There is not too much information available.

https://atomicinsights.com/ml1-mobile-power-system-reactor-box/

Only one was ever produced. I have a couple of papers in my library. One of those hard to find papers is now available online: http://www.osti.gov/scitech/servlets/purl/4673605

I also came across a guy who was an engineer on the project soon after graduating from college. We exchanged several emails that provided interesting details, but he also reminded me that he was in his seventies and he had worked on the project when he was just 23 years old.

Thanks Rod.

A good way to kill off the antiproliferationist lobby in DC would be to revive this proposal – the thought of 93% enriched uranium driving around through the countryside on flatbeds would make their heads explode.

Roughly what kind of capital cost per watt would you envision for the “Adams Engine” if if could be made today in small production quantities?

@Godel

We envisioned a system where the capital cost might eventually approach that of a complete combustion turbine power plant located in an area without existing natural gas pipelines. (Complete meaning that the capital cost of plant specific fuel supply infrastructure is included.)

I loved the video and am saddened that this technology never took off. I have dreamed of a power source like this. Thank you for sharing this information.

The video is interesting, though a bit short on technical details for the gas turbine, but don’t show it to any antinukes! It makes it look like the best purpose for an SMR is to keep endless columns of huge military vehicles trundling round the planet – the word ‘ Vietnam ‘ even made an appearance. I was reminded of Freeman Dyson’s account of working on the concept of a ship-sized spacecraft powered by small fission bombs shoving on a pusher plate. Their motto was ‘Saturn by 1970’. Unfortunately there was no military use at all for it. Somebody made a model of the thing loaded up with nuclear missiles, as a sort of 1960’s Death Star, and showed it to President Kennedy, who promptly killed the program.

ML-1 design details are about non existent on the internet. I’m wondering how decay heat is removed when the thing is moved? If it requires AC power it about has to be tethered to an electric power source for several years. If it’s by natural circ, I’d like to see how. This would seem to be the pinch point in any mobile SMR design. If you can’t “walk away” it is impractical. Once it was operated, and generated a power history, it would be an albatross around the neck of the owner.

@mjd

Spoken like a true “big plant” operator.

The thermal power of ML-1 was just 3 MWth. Getting rid of less than 1% of that through conduction to and convection with the surrounding air is not a big hurdle. The surface of the reactor shield might have been a little warm to the touch, but the hottest points inside the core would be well below operating temperature limits.

It’s true that not all technical reports on the device have been scanned onto the internet, but there are reports and reasonably detailed design papers on dead trees available in dusty library basements.

Thanks, good perspective, and I considered that possibility. I also qualified (and taught) on S1C in 1967, at 20MWt. And I put it through a refuel where they snatched the whole core in one lift, but still needed externally supported DHR capability. If you don’t need much electric power direct conversion works, like for space vehicles. I still think it is a trade off issue for SMRs. Some applications may be OK, but to be truly portable, if it won’t “naturally cool” DH it doesn’t seem practical. But without a market, it won’t be developed. I’m not saying it can’t be done, just saying the potential market niche seems small at SMR level. Especially considering the outrageous certification costs.

Even the dead tree archives are becoming rare. NRC is digitized only back to 1980, pre-that, you pay ~$0.85 per page for a copy of a microfiche page. Not much I want to know at that price. What is a real shame is the few folks who created that history, and are still with us, are not being debriefed more. And there is no central location point to capture the information for reference. In about a decade the first hand history will be lost forever.

You make me think of two things.

The first is, of course, the “Report of the Three Wise Men”, more officially known as “A Target for Euratom”, which I think everybody who’s interested in energy policy should read. Of course, the Suez Crisis was certainly uppermost in the minds of the foreign ministers of the six powers when they called for the preparation of this report!

The second is something called the “Brayton Isotope Power System”, a closed-cycle gas turbine developed for NASA in the 1970s. It wound up not being used for anything, & in the 1990s the parts were dug out of storage & converted into a solar-dynamic system, using a molten-salt heat reservoir. It performed admirably in ground tests, & was on the schedule to go to Mir, but was “de-manifested” for reasons not entirely clear.

@publius

Do you know what happened to the “de-manifested” repurposed closed cycle Brayton system?

I don’t, but I know someone who might. My best guess is that the components went back into storage at NASA Lewis Reseach Center (now NASA Glenn).

The last document I’ve been able to track down about it is NASA/TM-1999-208840, “800 Hours of Operational Experience from a 2 kWe Solar-Dynamic System”, by Richard Shaltens and Lee Mason. If my acquaintance who worked on the project (and first informed me about it) can’t tell me, tracking down one of them might shed some light on the question.

With passage of time, the people got used to other energy devices but more scared of nuclear energy. Today you will not be permitted to do what was routine in your working days. Perhaps Russia or China may take some rational decisions and get blackballed.

@Jagdish

Nuclear fear did not naturally arise with the passage of time. It was the result of a multi-pronged partly coordinated effort by people with logical, economic motives to suppress a competitor. Fear campaign can be undone by exposure and openness.