Positive Lessons Extracted From Cooper’s Paper On French Nuclear Experience

I wrote yesterday about the press conference announcing the release of Dr. Mark Cooper’s paper titled Policy Challenges of Nuclear Reactor Construction: Cost Escalation and Crowding Out Alternatives. Though I strongly disagree with the conclusions, I believe that the paper is worth reading because it can provide both cautionary information and some indications for ways to improve on past history.

Unlike Dr. Cooper, I am unabashedly in favor of the use of atomic fission as a source of reliable, emission free, inexpensive heat. Using fission to replace fossil fuel combustion can provide growing numbers of the world’s human population with low cost, reliable, clean energy.

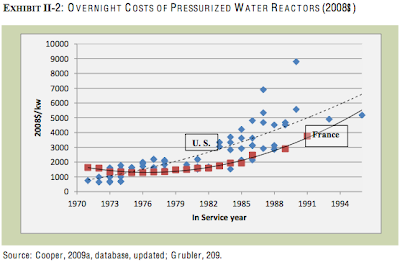

That said, I also recognize that Dr. Cooper has done a reasonably accurate job of presenting the actual numbers associated with building the world’s current stock of nuclear power plants. The nuclear industry did experience a rather dramatic escalation in construction costs well in excess of the rate of inflation. It did not achieve the predicted economies of scale in construction costs; bigger plants tended to cost even more per kilowatt of initial capacity than the early, smaller units. The last plants finished in both the US and France tended to be far more expensive and took far longer than initially predicted.

One of my issues with using the historical analysis that Dr. Cooper applied for future predictions is that it is based on an assumption that the participants in the next build cycle will make the same mistakes again. That assumption supposes that the people involved are less able to learn lessons than “independent” analysts like Dr. Cooper.

I have been around nukes for the past 30 years; people can apply many labels to them, but it would be wrong to say they refuse to learn lessons from past mistakes. There are few groups in the world who spend more time analyzing the past and trying to glean lessons for future actions – in fact, nukes are more often guilty of paralysis by analysis than of trying to move forward without learning lessons.

For example, Cooper identified a cost trend that went in a different direction than most of the other cost trends he found.

Historical data shows a clear relationship between multi-unit sites and costs in the U.S., with second and third units costing substantially less. However, this has the impact of making the reactor projects very large and raises concerns about excess capacity, especially given the economic slowdown and dramatic change in household wealth resulting from the financial meltdown.

(Cooper Policy Challenges Pg. 24)

If Cooper did not already have an anti-nuclear agenda, he might have tried to do some additional investigation to find out if the unit cost reduction trend continued with even more than three units at the same site. Though there are no US facilities with more than three units, there are examples in France and Canada with as many as eight units on a single site.

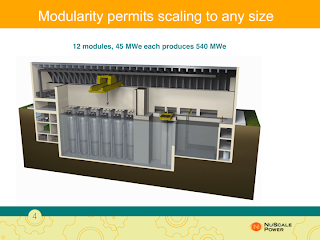

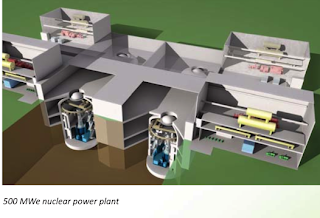

Though Cooper was unwilling to recognize the implication of his positive finding, knowledge of the multi-unit effect gives some encouragement for the kinds of large, multi-unit projects that Westinghouse, Kepco and Rosatom are developing around the world. It also provides encouraging reinforcement for the multi-unit nuclear plants that NuScale and B & W are proposing to build with many more units per site using their smaller modules.

The key reason why multi-unit construction showed cost improvement for later models is that the specific crew that learned on the first unit was able to turn around and apply those lessons to the second unit. Learning curve theory would show a potential for continuing improvement as the number of units built by the same team increases. Normally, the curve is based on a certain percentage increase as the cumulative experience doubles.

Another cost trend that Cooper identified was that there was a substantial difference in the rate of cost growth between various prime contracting firms.

However, there is a distinction between the companies. Bechtel built a large number and had lower costs, but even for Bechtel, there was a steady, moderate increase in costs. Two other constructors had low and moderately rising costs that paralleled Bechtel (Duke and UE&C)

(Cooper Policy Challenges Pg. 20)

In today’s nuclear industry, a result like that would lead to a number of efforts to share best practices and learn as much as possible about the differences in project management so that all constructors could move towards achieving results similar to the best performers. Of course, the energy business is a competitive one. What really might happen would be for a larger number of customers to gravitate towards the companies with the better records of performance. That movement would have the same effect overall – the cost growth would be far lower.

There are probably many reasons why the final plants in the first building cycle cost so much and took so long. One of the reasons that is not often discussed is a purely logical, human group behavior of working to hang on to a good job as long as possible. The people who were building those units could read the writing on the wall; there were no new projects for them to move to. Some were working on new skills and preparing to transition to operational jobs or other types of construction, others may have been nearing a planned retirement, and still others may have had no real plans at all for what they would do when the plant construction ended and they no longer had any work to do.

That natural group behavior would have resulted in many different ways to slow down progress. It would have been complicated by the fact that nuclear co

nstruction jobs were good paying positions that often involved some decent perks. I have talked to a number of people who participated in those building programs – they have shared stories of full of useful information about situations that contributed to cost escalation.

One story in particular I remember was from a former highly respected nuclear welder who owned a jewelry store in the Florida town where I lived in the late 1990s. He once told me about an assignment where he was called onto a site for a particular critical weld. Because it was difficult for the project manager to predict exactly when his services would be needed, he asked him to be on site a few days before the job was tentatively scheduled to take place. He spent several days in a hotel room collecting per diem and eating nice meals while he was waiting.

When the project needed his services, he worked as many hours as possible before taking a break for necessary sleep. He turned back around as quickly as possible and worked some more until the job was done. (That process gave him a pretty healthy boost with overtime pay, but the project managers were happy to pay because of the value of shaving time when working on a project where the completed plant’s revenue would be a $1-2 million per day.)

Once he finished the job, he was asked to hang around until it was tested, which took several days. He told me that assignment was not unique and that jobs like that could net him the equivalent of a month’s pay in just a week or two with only a couple of days worth of actual work. He told me that he knew some welders whose work did not pass the first or second retest – sometimes because they knew exactly what to do to fix the welds but they liked the lifestyle of being on per diem as long as possible.

My “take away” from hearing the stories I heard about the final stages of the first Atomic Age was – well, let’s not do that again. In my opinion, the very best way to avoid situations where people do not do their best because they do not want their job to end is to establish and maintain a sustainable industry where there is never a time when good people look forward and see no future for their skills. There is plenty of demand for reliable, clean energy in the world to make sure that highly trained people always have work to do building new power plants.

Also, Dr. Cooper may have been selective on countries chosen for the data. If you look at Korea (and to some extent Japan) you will see schedules and costs decreasing as the standardized designs are applied. Maybe that is why Asia is the current leader in nuclear new build.

@r margolis – Good point. Can you point me to good sources of data on South Korea’s experience?

In regard to Exhibit II-2, please note that the US costs began to spike dramatically after the TMI event as a result of the design changes mandated by the NRC.

I worked on the prudence case for Beaver Valley Unit No. 2 in the late eighties, where we had to justify $3.9 billion in cost increases, a substantial portion of which was due to post-TMI requirements issued during the project. Also, the rate of inflation during that project, begun in the seventies, was much higher than what we are seeing these days. Every case was different of course, but that general industry trend explains a great deal of what happened. The effect of modular construction and uniform design currently underway should bend the cost curve considerably. Though there will always be case-by-case sticks and bricks issues, clearly, lessons were learned.

Interesting analysis as always, Rod. On that note though, if a linear projection of costs based on historical data is inappropriate (i.e., due to learning), how would you counter-propose cost projections? While it’s obvious some cost savings are to be achieved through construction experience, especially with standardized designs, some of these costs are exogenous to construction management itself – i.e., some of this has been the rising cost of raw materials, etc. There’s also other intangible factors like the ROI that must be guaranteed to secure investment (particularly if other sources are receiving heavy subsidy and don’t require the large up-front capital investment). In that sense then, do you have any speculation as to what you expect trends to look like, in light of these other factors?\

@Steve – cost estimating is a fairly well established discipline. For estimating the effects of learning curves, I would recommend following a methodology similar to the one described in the Pricing Handbook from the FAA http://fast.faa.gov/pricing/98-30c18.htm#18.1

It is important to understand that learning curves do not necessarily apply across different designs, they need to have inflation factored out, and you need to remove the effects of nonrecurring items.

One of the reasons that smaller units can have steeper improvements for the same total output capacity is the fact that more units are required, giving more opportunity to approach the asymptote defined by basic materials, real estate, and fixed overhead costs.

One quick comment about inflation, you also have to consider when the money was borrowed, the interest rate at the time, the compounding in that particular period for each and every tranche and so on. This is especially so for the seventies and eighties. Explaining that in hindsight had to be done very carefully. The deeper you dig into causation and factors outside of the control of the constructors, the flatter that Exhibit II-2 curve becomes. The way I recall Beaver Valley’s No. 2’s most simplistic narrative was: the PA PUC ordered it built to power the steel mils as old “acid rain” producing coal plants deteriorated, then ordered cost-driven delays as the economy slowed – pushing it into the TMI window, then, after the steel mills shut down, questioned why this “excess capacity” was needed at an extra $3.9 billion. Most of what I did was on the more micro-level engineering and construction technical issues, but that was the Readers Digest version, if I recall correctly.

@Bryan – you bring up an interesting point about interest rates. I clearly remember the rates achieved right about the same time as TMI. As a midshipman at USNA, we were offered “car loans”, now called career starter loans, by various financial institutions at below market rates. I had heard all about the great deals offered to my upper class of rates like 4 and 5%. In the fall of 1979, the best deal I could get was a 13% loan from the Navy Mutual Aid Association – a life insurance company. However, I took it because it was a heck of a lot lower than the 18% loans being offered by the car dealers in town.

Those of you who like to run numbers can easily figure out the doubling time of a loan that is being used to pay for a non producing power plant and see that interest costs of borrowed money accounted for a significant portion of the final cost of the units that entered service in the 1980s, especially the ones that took ten years or more to build.

Rod, now imagine all those 1970’s payday loans interest fee stacking up to $1 million a day (in 1989 dollars) and the critical path to completion riding on your buddy’s last few welds passing the x-ray test. Because it gets down to that, at which point no one is interested in exhibits of any kind, just progress. That is why you will hear stories of people sitting around at the end. You may read newspapers for a week at some point, then “no one goes home until that needle in a haystack is found, I don’t care if it’s Christmas.” No one can plan, schedule, cost estimate or manload that kind of thing, even in hindsight.

When the nuke plant I was at in the early 80s went commercial, the PA PUC refused to let it into the rate base. The utility sent our a bill explaining how they had to sell the lower cost nuke electricity to people in NYC and sell oil generated electricity to its own customers. The PUC changed their minds.

Rod, I am a big fan of incentives to encourage the result desired and penalties to discourage sloth and unproductive behavior. A prime example of this might be following the Northridge, CA earthquake which brought I-5 just north of Los Angeles crumbing down. The state had a choice of allowing CalTrans to rebuild the shattered overpasses and roads or let the bid to C.C Meyers, a private and well-known construction firm.

The result: Meyers paid his crews bonuses based on performance of completing the project early, as C.C. negotiated that in his contract with the State of California. With I-5 being the critical north-south link for transportation, every day it was down cost the State in revenue. By incentivising Meyers to complete the task as quickly as possible, commerce and tax revenues could be restored. If CalTrans had been given the bid it is highly unlikely that they would have completed the task at the same rate, or anywhere close.

Moral: Pay skilled workers well but don’t leave the check blank. Human nature tends to cause even the most diligent person to err on the side of personal self-interest.

This is an excellent point: you get what you pay for, but if you pay before you get, or you pay without thoroughly testing, inspecting, and generally shaking-down the completed product, you have no way of knowing that what you got is what you paid for.

Cost-plus contracting is almost never justified, excepting, perhaps only when no one has done in the past what you want the contractor to do, and you have lots of folks to keep a very close eye on how the contractor is spending the money. Since nuclear construction has been done before, pure cost-plus, or cost-plus fixed fee ought to be out of the question.

Setting a target cost, a target date for completion, and a structure of incentives that decrease as the contractor’s profit as costs go up and the date slips, and increase the contractor’s profits as costs go down and the completion date is met, along with the potential offered by surety bonds for (sub)contractors who fail to perform as required ought to be able to provide an accurate upfront price signal and time signal to power companies as to when a plant will be completed, and that it will be completed at a reasonable price. Substantial incentives to workers and unions – perhaps in the form of project labor agreements in union areas – for completing their jobs on schedule or ahead of schedule (to ensure that the financial gain they might realize from going slow will be less than the gain they receive from completing the job as fast as quality and safety allows) ought to be used, as well. Plus, the social pressure that workers and unions whose completion bonuses are impacted by the lack of speed or quality of others can apply to others who are falling behind are a natural and healthy way of ensuring an optimal schedule.

The key in smart contracting in large projects like these is ensuring the unity of all interests, so that everyone wins together. The way to a cluster-“failure” is allowing anyone to believe they can get a better deal by gaming the system. Everyone hangs together, or they all hang separately.

The only variable that can’t be accounted for is Mother Nature (but that’s what insurance is for), and the NRC, but a unity of interests also helps here as well. If the NRC is stirring up needless trouble and causing needless delays, and the power company, the contractors, the unions, local industries and businesses, the county/town, homeowners… all start calling their CongressCritters, that trouble might just go away.

Dave, you might be interested in this bit of musing regarding surety bonds. I went into that business after the last round of new nuclear builds and have more than a few opinions:

Surety Bonds for Nuclear Energy Facility Construction Cost-Savings

The author of this uhm… ‘study’ used overnight costs for the biggest AP1000 customer – China (which are indeed $2000/kw), then essentially claimed that costs were rapidly escalating by using a US figures plus financing cost. What an idiot.