Living the Renaissance – NRC License Review Budget Constraints

During day 2 of the American Nuclear Society annual meeting, there was a well attended session titled Living the Nuclear Renaissance. It included four speakers with detailed, day to day knowledge of the issues associated with getting a new plant through the very important step of obtaining a US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) combined Construction and Operating License (COL).

Dave Matthews, Director, New Reactor Licensing, US NRC set the stage with a talk that started as an introduction to the NRC – apparently for the foreign members of the audience who are not fully aware of how the US nuclear energy regulatory system works. Dave then described the process that the NRC would prefer for license applications to follow – obtain an early site permit at a measured pace, find a vendor with a certified design, and then apply for a COL using the permitted site and the certified design. From his point of view, one of the unforeseen challenges facing the NRC today is that many applicants have chosen to try to turn that serial path – which would take approximately 6 years assuming that the vendors have already obtained a design certification – into a parallel path with several steps happening at the same time.

The parallel path chosen by the applicants leads to an increase in the rate of consumption of NRC resources. He was proud to claim that, so far, there had not been any delays or schedule changes caused by the NRC’s failure to deliver on a promised schedule. However, he told the audience that he had to often remind applicants of their responsibility to meet the projected license schedule, which he described as a contractual agreement between the regulator and the regulated.

He then explained that the NRC’s capacity to handle a large number of parallel operations was being stressed under current budgetary constraints and he did not expect to receive any significant budget increases in the next several years. Under the circumstances, he expects that there will be times when applicants will be told that their applications will not be pursued until busy people finish their currently assigned tasks and can be reallocated.

Greg Gibson, from Unistar Nuclear, described a different side of the resource and management challenge when he mentioned receiving more than 150 Requests for Additional Information (RAI) on a single day with a required 30 day turnaround. One example request was to provide the screen mesh size used for a particular water sample taken by an services contractor at the site as part of an environmental survey. Apparently, frantic telephone calls were required because the particular person who took that sample was on vacation.

Of course, that was just an example story told by a high level manager about a memorable part of the response process. Though I do not know any additional specific details about Unistar’s COL application, I know a bit about how large organizations function and respond to official government questions. I can just imagine the drain on company resources and the communication challenges associated with mobilizing a focused team to answer such a large set of questions in such a short period of time. I expect that a lot of other work would come to a screeching halt during the time that answers are being researched, written up and reviewed through several divisions, work groups, contractors, and layers of upper management.

I am sure that Unistar and other applicants would prefer a more measured stream of questions, but the NRC probably works more efficiently if it is able to deliver batches of questions to its applicants. In both talks, the regulator and the regulated described how the process is expected to improve with subsequent reviews of projects based on identical designs and identical paperwork – where possible – as previously approved projects. That expectation is built on the logical assumption of one question leading to a single completed answer and a single resolution which would then be applied to all subsequent applications of the same design.

During the question and answer session, someone else beat me to my first question for the NRC – if the NRC is a fee recovery based agency that is required, by law, to recover 90% of its budget from fees paid by current licensees and new plant applicants (the rest of its effort is assumed to be for the federal government or other agencies that are not subject to fees) why is there no expectation of budget growth as the demand for new nuclear power plants grows and the number of new applicants increases?

As Mr. Matthews explained, the limitations on NRC resources are determined by the normal federal budget process of executive branch submission and congressional review, authorization and appropriation. That process is what sets the limitation on NRC capacity for reviews. Given a certain budget for the year, the agency then determines the fee structure that is required to recover that amount of money. No applicant, no matter how qualified, deep pocketed, or motivated can assist the NRC directly by providing additional resources. The only way to increase the regulatory agency’s capacity so that it is not the limiter on the rate of new nuclear power plant construction or on innovation in the field is to convince the executive branch budget submitters and/or the congressional reviewers to increase their total obligational authority.

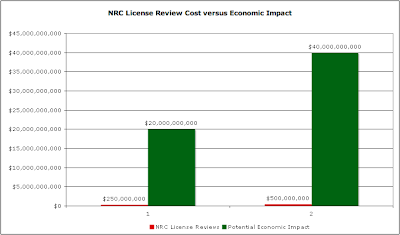

Let me put the challenge into graphical form using the following rough order of magnitude numbers. If we assume that there is a desire to build 100 new 1000 MWe class nuclear reactor plants in the next 20 years, there will need to be approvals provided for those projects within the next 15 years, assuming a relatively constant construction period lasting about 5 years. (With the amount of excavation, concrete pouring and steel bending, there is not much chance of reducing that by more than a few months.)

Let me put the challenge into graphical form using the following rough order of magnitude numbers. If we assume that there is a desire to build 100 new 1000 MWe class nuclear reactor plants in the next 20 years, there will need to be approvals provided for those projects within the next 15 years, assuming a relatively constant construction period lasting about 5 years. (With the amount of excavation, concrete pouring and steel bending, there is not much chance of reducing that by more than a few months.)

If the current projection of 42 months for a COL continues, that means that the last application will have to enter the pipeline within 11.5 years in order to be approved within 15 years. That leads to a need to accept and begin processing 9 new applications per year. I am going to make a bold assumption that we will at the very least, continue building at the rate that we can establish and do not go through another trough in new plant construction.

I am greatly simplifying the queuing theory math here, but it looks to me like the NRC will soon need to have the capacity to process and move forward approximately 30-35 applications at all times. I get that result from the fact that 9 applications enter the pipeline each year but the pipeline does not deliver any approvals until 3.5 years after the first application enters. If the first few applications take longer because of the nature of first of a kind or reference projects, the pipe will continue to fill while those applications are in process. That is, of course, unless the government simply throttled the rate of delivery to match the rate at which the agency can move the applications forward.

One thing that people have to remember is that the applicants here are not in line for a cup of coffee, but for approval to build a major new source of clean electricity where each approved application can represent the start of a construction project resulting in several thousand jobs lasting 5 years and several hundred continuing jobs that will last for 40-80 years and never be moved overseas.

It is not unreasonable to assume that each approved license could result in an investment decision of $4-10 billion dollars. If the agency is sized large enough to process the arrival rate of 9 new applications per year, the total monetary impact of its process would be on the order of $40-90 billion per year in 2009 dollars. Right now, the new license application review branch of the agency has an annual total obligation authority of about $250 million per year with a projection of flat budgets for the next several years and a processing capacity that appears to be nearly completely taken up by 16 or so applications it has currently underway, approximately half of what it will need to be able to process in order to build 100 new reactors in 20 years. In other words – a $250 million budget would enable only $20-45 Billion in economic activity.

If a pipeline has a component with a flow capacity that is less than half of the demand, the flow will be constricted by that component and it will be subject to stresses than may lead to failures.

None of that argument provides any available slack capacity to address innovative new designs or new types of fission power for uses that are not central station electricity production plants.

If this discussion is confusing to you, be assured that you are not the only one who is confused. In the hallway after the meeting, I learned that many potential NRC “customers” are deeply frustrated by the idea that they may have to wait in line for several years while the market continues to change and electricity needs continue to be met by burning dirty fossil fuels. As businessmen they cannot understand why they have no ability to increase the government review capacity.

The real answer to this dilemma is a concerted push to move the executive branch and the legislative branch of the government to a position where they do not use the NRC’s budget as a sneaky throttle valve new nuclear plant construction. If that is the goal, it needs to be more openly stated and debated. We cannot allow it to be sold as a fiscally conservative measure designed to reign in government spending, which is certainly not greatly influenced by an agency with a total budget of $1 billion. Besides, the fees collected from the applicants will, by law, be sufficient to recover the cost of the investment.