In a turbulent electricity fuels market, nuclear fission fuels provides some price stability

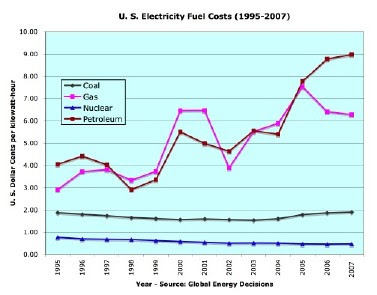

One of the trends that has become obvious to the fuel traders in the electrical power business is that their job is quite a bit more “interesting” today than it was 5-10 years ago. Instead of being able to reliably contract for coal, residual oil or natural gas at stable prices or with moderate inflation escalation for 10 years at a time, the traders are finding rather wild price swings and few offers of long term contracts at rates even close to those in expiring contracts.

State regulators have taken notice and quietly begun to implement rules that allow more frequent adjustments in the electricity sales price. A new trend is the ability to recover projected costs in advance rather than waiting until the returns are in for previous years to build a rate case.

When fuel represents 60-90% of the cost of power generation – like it does in most fossil fuel powered plants – it is vitally important for the stability of the utility companies to be able to pass those rapidly changing costs on to consumers. The alternative is a California 2001 style financial crisis where utilities approach bankruptcy in a squeeze between their costs and their obligation to provide power at fixed prices. Unlike many businesses faced with increases in raw material costs, electric utilities are often legally obligated to continue selling their product, even at a loss.

In this turbulent fuel market, the 104 operating nuclear power plants in the US are providing a bit of stability. Not only are they being operated as much as possible, with average capacity factors exceeding 90% during most of the past 6 years, but the owners have been investing steadily to increase their ability to produce power. According to Tom Christopher, President and CEO of AREVA NP Inc. and CEO of AREVA, Inc., these power uprates can add as much as 130 MW of capacity to an existing nuclear plant.

Until reading Mr. Christopher’s article, I did not realize that there are even some state public utility commissions that are mandating uprate projects. Though he did not specifically say it, I presume that those mandates occur when the commission’s economic analysis indicates that the nuclear plant uprate is the lowest cost option for new capacity supply.

Though there is a lot of attention being paid to the rather astounding cost projections for new nuclear plants, what is less often discussed is the higher long-term risk of cost increases for other types of power projects. Even formerly predictable and “cheap” coal is getting some attention by some serious cost analysts who project that the rate risk could be huge for a new coal project in today’s market.

With nuclear power projects, many of the cost and schedule risks – though certainly not all – are within the control of the contracting customer. Once the project is up and running, fuel prices are rather low, and there is little risk of the later imposition of carbon emission taxes.