Impressions from the ANS Utility Working Conference 2017

With generous support from several Atomic Insights readers, I was able to attend the welcome reception and the first day of the annual Utility Working Conferenc organized by the American Nuclear Society (ANS). This year’s conference title was The Nuclear Option – Clean, Safe, Reliable & Affordable.

This event has been a fixture in the August calendar of nuclear utility company leadership, nuclear plant operators and maintainers, and nuclear equipment and service suppliers for the past quarter of a century. There are usually invited speakers from government agencies that impact the main attendee groups, including the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the Department of Energy.

The conference is a learning opportunity. People develop their contact networks, candidly share both successes and challenges, find out about newly developed problem solutions, and see some demonstrations or literature about new developments in technology.

It’s also a family affair that has almost always been held at the Amelia Island Resort, which is on a barrier island off of the northeast coast of Florida. There are well-maintained beaches, expansive swimming pools, ocean view rooms, golfing, tennis, bike paths, and plenty of other reasons why families willingly attend while mom, dad, or both attend the sessions that help them in their professional lives.

The welcome reception is a casual affair where even some of the most sartorially-minded participants have been known to wear “resort-wear” consisting of untucked shirts, shorts, and boat shoes. Children and spouses attend for the food and the creative swag at the vendor booths.

ANS and the industry leaders have been making a serious effort to encourage companies to send a wide range of attendees, including as many of their younger employees as possible. It’s a good way to reward exceptional performers with a solid return to the company in terms of valuable knowledge and personal contacts.

Concern for the future

The event started less than a week after the sudden announcement from Santee Cooper and SCE&G that they had decided to immmediately halt construction on V.C. Summer 2 & 3. The utility host for the conference was Southern Company, the parent of Georgia Power, the lead owner of the Vogtle 3 & 4 construction project.

Though construction work at the Vogtle project is continuing, everyone at the conference understood that the owners have not yet made a final determination about whether or not they will be able to complete the project in the wake of the Westinghouse bankruptcy filing.

There was a different atmosphere and attitude among conference participants in comparison to UWC 2010, the last time I attended a UWC at Amelia Island. That meeting was in the pre-Fukushima days when memories of high and rising natural gas prices were only two years old. There was still a lot of talk about a Nuclear Renaissance.

I was introduced to several people who would soon become colleagues on the B&W mPower project for the next three years.

There was also some muted sadness about the fact that the 2011 UWC was being planned for a different resort in Hollywood, FL.

The attendance at that 2010 meeting was so large that it strained capacity limits at Amelia Island. The plenary sessions had to be moved to a huge, air-conditioned tent because the largest conference room couldn’t hold enough people.

The event returned to Amelia Island in 2014 after three years in Hollywood. I’m sure there were numerous regular attendees who were pleased with a return to the traditional venue even if not happy about the underlying reasons that the larger conference spaces were no longer necessary.

Following the welcome reception, I had the cultural experience of watching an episode of Game of Thrones in a hotel room full of young nuclear professionals. I was amused by the side commentary, near dorm room atmosphere and by the frustration expressed by some of the attendees with the lack of an up-to-date HD TV with better than 720p resolution or at least an HDMI connection.

I also learned that there are some utility core designers that have developed considerable dexterity with fidget spinners during lulls between outages.

After taking my leave from the younger crowd I engaged in an interesting poolside discussion with a member of the Entergy leadership team who tried to explain why the company had decided to exit its merchant nuclear generating plant business in the Northeast. We agreed to disagree on many of the circumstances, but agreed that part of the problem was cultural. The electricity business and political climate in Louisiana is quite different from the same business and its political climate in the Northeast.

Case for Nuclear

The opening plenary session was organized on the general theme of “The Case for Nuclear in the Nation and the States.” It might seem a bit odd to think that such a session would be necessary at a meeting of the American Nuclear Society, but even choirs needs inspirational messages from skilled preachers now and again.

In fact, successful evangelists understand that it is never a waste of time to preach to the converted or to fire up the choir. There is no better way to spread whatever message it is that the evangelist wants to be widely adopted than to create committed, excited, and empowered messengers.

Donald Hoffman, the President and CEO of Excel Services Corp., was the session organizer and moderator. He has been traveling and working diligently to make the case for supporting nuclear energy in numerous state capitals and on his home turf if the region that some call the DMV (District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia).

He planned the speakers to make the case for nuclear from a range of perspectives and angles.

Robert (Bob) Coward is the current president of the ANS and the principal officer of MPR, a well respected engineering and technical services company originally founded by three escapees from Rickover’s Naval Reactors organization. He spoke about his firm belief in the importance of nuclear energy and in reliable generation to serve as the foundation of an always on and available power grid.

He provided a first hand anecdote about grid level storage; MPR has provided engineering support services to PG&E for a project to build what is currently the world’s largest grid-connected storage battery. That battery, installed as part of an efffort to ensure grid stability in Southern California in the wake of the one-two punch of closing San Onofre followed by the Aliso Canyon natural gas storage facility leak, can store 100 MW-hrs of electricity.

When running, San Onofre delivered that amount of electricity to the grid every 3 minutes.

Coward asked the attendees to remain optimistic, to learn as much as possible about the unique capabilities of nuclear in comparison with alternatives, and to share nuclear knowledge more widely.

Steve Kuczynski, the Chairman, President and CEO of Southern Nuclear explained once again the reasons that Southern is so strongly supportive of an “all of the above” energy portfolio that includes a strong nuclear component. He described how Southern has maintained an R & D arm for more than 40 years and continues its leading work with advanced technology development including partnering with the DOE, small companies, universities and national labs on several advanced reactor development projects.

Then he turned to the topic that everyone in the room was waiting for, the Plant Vogtle expansion project. He spoke about the numerous challenges associated with restarting a nuclear plant construction industry, including rebuilding a hollowed out supply chain. He talked about disappointment with the failure of the prime contractor.

He described the work that has been done in the past several months to improve construction performance and worker productivity while also working diligently to create solid project schedules and estimates of cost to complete the project. He explained that Southern Company, through its Georgia Power subsidiary, is only a 45% owner and has three development partners whose concurrence will be required with any decision about the projet’s future.

He expressed his deep personal interest in moving forward and also stated that his company thinks it is probably the right direction. However, negotiations continue and the final decision will require supportive decisions by the Public Service Commission. In other words, stay tuned.

R. Shane Johnson is the Deputy Assistant Secretary in the Office of Nuclear Energy for the Department of Energy (DOE). He came bearing the message that the Trump Administration wants to follow where the industry leads. It believes that the government has severely hindered the development of nuclear energy and that it wants to get out of the way.

To do that, however, he emphasized the fact that the industry has to identify and prioritize the actions that the government should take.

He quoted both President Trump and Secretary Perry’s strongly supportive words about nuclear energy.

President Trump: “We will begin to revive and expand our nuclear energy sector…which produces clean, renewable, and emissions-free energy. A complete review of U.S. nuclear energy policy will help us find new ways to revitalize this crucial energy resource.”

Sec. Perry: “If you really care about this environment that we live in…then you need to be a supporter of this [nuclear energy] amazingly clean, resilient, safe, reliable source of energy.”

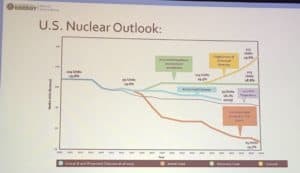

He then displayed the below slide that illustrates various future paths that are possible for the US nuclear industry.

Aside:I’m quite partial to the upper line and its associated notes.

The DOE has moved to revise its definition of advanced reactors to include any reactors that have not yet been commercially deployed. That change was aimed at reducing infighting and fratricide so that all of the people seeking to improve on our existing technology will see that they share at least some common goals.

Johnson introduced a new Funding Opportunity Announcement (FOA) that has not yet been finalized or issued. It will offer several tiers of funding or in-kind support from national labs and the NRC. As the government’s expenditures increase, the portion of funds that will be expected to come from the private sector will also increase.

The FOA will have much broader technology boundaries than those that defined the limits for such programs as the small, light water reactor licensing assistance effort.

John Rosales, a commissioner on the Illinois Commerce Committee, described the political effforts that led to the passage of the Future Energy Jobs bill that provides sustaining support for three nuclear units – the Clinton plant and the two unit Quad Cities station.

He emphasized that the bill could not have been passed without expanding its scope to include substantial support to wind and solar energy development.

I thought about his talk during a later conversation with a Clinton plant employee. He told me that one of the real challenges for his plant is the fact that it is in an area of the grid where it shares its transmission lines with a huge number of wind turbines. When the wind is blowing strongly, the electricity from those machines often fills the transmission capacity, requiring Clinton to reduce its output and its sales revenue.

We agreed that it was a bit unfair that nuclear plant projects have always been required to develop sufficient transmission capacity and to include the costs of that transmission infrastructure as part of the project cost, but that wind developers are often allowed to ride on the established grid, even to the point of displacing other generating sources whose power is just as emission free.

Following the plenary sessions, I attended two very interesting breakout sessions about advanced reactors, but I think it might be appropriate to cover those in separate posts.

I must admit that most of my colleagues consider nuclear doomed: natural gas prices too low and CO2 not considered a problem. Many consider themselves lucky that they are close enough to retirement age. Maybe a good pitch to the choir is still needed and not just for the few that can attend conferences.

Was the name/number of the funding opportunity announcement provided or is it still too early for that?

I’m encouraged by the Trump representative’s words, especially the part about how the govt. has hindered nuclear development. But I’ll wait and see if it’s just lip service.

Most of the “regulatory reform” I hear people talking about (e.g., credit for lack of CO2 emissions or grid reliability, etc..) is actually what I would call policy reform. Actual regulatory (and QA) relief is far more important, IMO, and I don’t hear anyone talking about that. Would Trump et al, actually be willing to reduce regulations for nuclear, like they are for fossil?

“To do that, however, he emphasized the fact that the industry has to identify and prioritize the actions that the government should take.”

Sounds great, but I have a feeling that the industry won’t have the balls to ask for the meaningful changes (regulatory/QA relief) that are needed. How do *I* get on that panel, that will advise the govt.? Me. Jim Hopf. I’m serious.

Jim,

I agree. We’ve chatted before about the QA aspect in nuclear driving up costs and may not have always agreed, but the bottom line is that the implementation of our current nuclear regulations (including QA) is extreme and has created a negative feedback loop that is strangling and killing the industry. We need to rethink every single aspect of how we regulate our industry, paragraph by paragraph, and (more importantly) look at the culture within the regulator itself.

If I were writing to Trump, I’d say something to the effect of:

Completely rethink the 10 CFR codes and reform the NRC

Revise the radiation protection codes to allow higher, more reasonable exposures

Simplify the design certification process (if the plant is using accident tolerant fuels, is a “low pressure” plant (like molten salt designs), or is in some way a “walk away safe” design then the reguatory review and any nuclear QA requirements should be minimal) with a focus to limit reguator involvement for the entire life of the plant as much as possible

Revise the tax code to foster an environment where investors will want to invest in new projects or designs

Revise and reduce the plant security requirements for nuclear plants

Allow US companies to more easily sell our nuclear designs and technology around the world

Rtk,

We’re in total agreement. Concerning QA requirements, I saw Rod post this in his Twitter feed:

“Couple of reasons: oil & gas modules don’t have to meet NRC inspection criteria. Shaw wasn’t careful about SSC classification”

Indeed. I’m convinced that competing industries don’t face anywhere near the same standards, and it’s critical that nuclear QA standards (e.g., SSC classification) be in line with actual hazards. The industry needs to push back hard, and not give away the store in this area.

This is particularly true for SMRs, given their inherent safety and much lower potential release. Developers are saying that even if everything fails, there wouldn’t be radiation levels above the range of natural background anywhere outside the site boundary. It leaves me wondering why almost everything isn’t NITS. Certainly, ITS components should be limited to the NSSS itself, which would be completely built at the central assembly line factory.

Rtk,

You spoke of the need for a grounds up rethink of the entire body of regulations and QA requirements, and also of cultural issues.

Again, I totally agree, especially for SMRs that are essentially incapable of harming the public. SMRs make a large sacrifice of economy of scale to achieve huge, fundamental safety advantages, and we need to “take credit” for those advantages if they are to be economical. In PRA terms, we don’t need a release frequency of 10-10. We need to ask what requirements can be relaxed for SMRs (e.g., NuScale) so that we are back at 10-6.

We need to essentially start over, for SMRs, but there may be some material out there that we can use. I’ve heard that research reactors face much less daunting processes (licensing, fab QA, and operation), due to their lack of ability to cause significant harm. Well……, since that is also true for SMRs, perhaps we can use the research reactor process as a model, or starting point at least.

Another notion would be to use how dry storage casks are regulated as a model. Once a cask is designed, you can build and deploy as many copies as you want, w/o further licensing activity. Deploying casks at different sites requires no NRC licensing, but only a modest evaluation which shows that key site parameters (seismic, temperature ranges, etc..) are bounded by the generic licensing analyses.

Rtk,

You also referred to culture and the (anal) implementation of requirements, in addition to the requirements themselves. IMO it’s not only NRC, but many perhaps most people within the industry itself.

I’m almost at the point where, if it were up to me, I’d go with an inherently safe SMR design, but I wouldn’t let anyone who’s worked in the industry over the past decades anywhere near the project. Nobody who has been indoctrinated in nuclear industry “safety culture”. Instead, I would hire people from the oil industry perhaps, or anyone else who has a “get it done” attitude, as opposed to people prone to beard-stroke endlessly over minor issues.

As for NRC culture, they will probably not be willing to make any of the changes you and I have discussed. Note how they’ve been ignoring the petitions to abandon LNT. This makes me wonder if they could be forced to make changes through a court challenge. Refer to the post I’m about to make in Rod’s more recent article about an LNT petition drive.

The guidelines for testing/evaluating simulators are based on legacy LWRs. There were difficulties convincing the NRC that the AP1000 simulator test coverage was fully addressed by standards that were designed around BWRs and PWRs. Evaluating simulator response with reference plant data was also a challenge.

While I understand the value in trying to avoid despair, whistling past the graveyard can be counter-productive. Maintaining morale is one thing, but letting people think that “things will still be OK” and that they will be able to go on doing what they’re doing, w/o significant change, is not a path forward. This moment needs to be a wake up call.

Contrary to the event title, new nuclear is NOT affordable. At current cost levels, the “case for nuclear” is weak to non-existent. If you let people think that, despite extremely high costs (even vs. renewables), people are still going to build nuclear plants for weak/lame reasons like fuel diversity, grid reliability or national security through maintaining nuclear leadership, they are going experience profound disappointment in the future. Ain’t no one going to make new build decisions based on such things (not at these costs, anyway).

Nuclear can tolerate a somewhat higher cost than competitors. However, the construction cost and schedule must be predictable and the operation reliable. The AP1000 failed on the former. We’ll see how well it operates next year.

I am curious as to how other large (10 to 20 billion dollar) construction projects have fared over the past 10 years in the US. How much of the failure is due to the “nuclear” aspects of the job? What are some other infrastructure projects of this magnitude, and how did they do on cost and schedule?

I’m sure there is plenty of blame to go around among those involved in the new construction: Westinghouse, CBI/Shaw, SCANA, the NRC, and various intervenors. And I’m not minimizing that, rather I’m looking for lessons learned. Are there successful projects? What do they do differently?

The biggest problems were the fact that WEC was still designing the plant as it was being constructed and problems with the supply chain both in vendor quality and adherence to schedule. I would say these were the fatal problems.

I was talking with someone involved in the construction/startup of St. Lucie 2, which was considered a great success in the early 1980s. He was surprised that there were 5000 people constructing the “modularized” AP1000.

About 90% of the components were delivered to the site. The big cost remaining was labor. Labor productivity never seemed to improve. Part of the reason was idleness while waiting for design packages. Another problem was the difficulty in getting the required numbers of nuclear quality workers. The AP1000 containment is pretty tight so once work had to be done inside it would have to be well coordinated.

Could SCANA have had better oversight? Sure, but remember Southern was also in the same boat. When SCANA finally did get an opportunity to look at the internals they must have blanched.

There was some inconsistency on the part of the NRC, some of it HQ vs Region which I have seen at other plants. I don’t believe these were a significant cause of the delays. Intervenors played no significant role in the failure. They were almost invisible.

5000 onsite workers does sound like a lot, I don’t really know. Don’t forget they were building two units almost simultaneously. But still, 5000 at say $150K a year is $750 million for payroll, or $3 billion over 4 years (first concrete: March 2013). Huge, but not 25 billion huge.

I heard the construction was using the same work controls for the balance of plant as they were using on the safety related work. Can that possibly be true? Why would anyone think that is a good idea? I can see that doubling the cost of the BOP construction.

Yes, it is apparently true that the BoP was being built to the same standards as the nuclear island.

The $25 billion also includes the additional 3 years beyond the late 2020 date provided by WEC’s fantasy forecast. These people had to be paid whether they were doing useful work or waiting for paperwork.

James,

Our nuclear culture is like a cult (maybe even a death cult). We worship ALARA and follow it to areas beyond reason. We worship technical thoroughness only to lose sight of the ability to actually build and operate something. We have become completely divorced from reality, and it is our own fault. We never stood our ground and let requirement-creep advance and advance and advance and now we are near the edge of the cliff.

Nuclear, as it is currently done, is not cost competitive. Period. Why would anyone ever invest in it? Nuclear is too full of red tape for most people to want anything to do with it. I believe that we have to be (to use religious imagery) purged of our own wretchedness if we are going to survive. It will have to get worse before it gets better.

While it is bad, I still have hope. The signs are that things are starting to change at the grass roots level. We need to build up this movement and force the regulations and culture to change. The NRC will not change enough. It is too invested in the status quo for that. Our culture could change, we enough people let it (but that would require the dissolution or restructuring of many of the established institutions / companies…) We need something new/different. Its time to hit the reset button and start over.

Cult is an appropriate term. How many meeting are opened with the rote recitation of one of INPO’s pillars of nuclear wisdom? After about the 375th time, you start to tune it out.