Beyond Electricity – Fission as a Source of Process Heat

One of the great things about working in a city like Washington is the occasional opportunity to attend fascinating gatherings of forward thinking people. Yesterday I was able to take a few hours off in the middle of the day to attend a lunchtime talk sponsored jointly by The Heritage Foundation and Third Way titled Beyond Electricity: The Next Generation of Nuclear Power.

The invited speakers were Fred Moore, Global Director of Manufacturing & Technology, Energy, The Dow Chemical Company, and John J. Grossenbacher (VADM, US Navy, retired), Laboratory Director, Idaho National Laboratory. They provided two different perspectives on the opportunities associated with using TRISO coated heavy metal particles to enable nuclear reactors that can produce useful quantities of heat at a temperature of about 800 C and higher. This is really cutting edge technology that has slowly developed from an invention by Rudolf Schulten sometime in the late 1950s, which itself grew from an idea proposed by Farrington Daniels, a US chemical engineer who proposed high temperature gas cooled reactors (he called them piles) in the period immediately after World War II.

My main disappointment in the session was hearing that the “Next Generation Nuclear Plant” (NGNP) has the stretch goal of being operational by 2021.

Other than the timeline, I thought that both speakers shared some inspiring thinking.

Customer Perspective

Fred Moore provided some rather sobering statistics about just how massive his company’s energy needs are, and kept emphasizing the fact that he was talking about “just one chemical company.” Here are a couple of facts to think about – Dow Chemical uses roughly 1 million barrels of oil equivalent PER day in its world wide operations for both raw material inputs, electricity, and process heat. As Moore also pointed out, his company is IN COMPETITION with other energy consumers and recognizes that growing demands for hydrocarbons without a growing supply will inevitably lead to increasing prices.

I am happy that Dow and a few other customer companies have joined the NGNP Industry Alliance. They offer a perspective that can open up many lines of inquiry and applications that traditional nukes (I think of that term as a hard earned collective “call sign” for people who have been trained in nuclear related technologies or operations) might not have considered. Nearly all nukes that I know are just now realizing that there is more to the energy market than producing electricity in 1000 MW chunks. Mr. Moore’s talk included mention of much smaller plants, series production methods, plants that could be co-located next to refineries and chemical plants, and the need for reliable cost estimation methods.

One idea that I know that Dow and others have brought to the NGNP group is the fact that there is really no benefit from stretching too far in terms of ultimate temperature. For most chemical processes, 800 C is hot enough and it is well within the range of proven materials. Going much hotter, which was one of the original research goals for NGNP, is just not worth the risk yet. The material science above that temperature needs a lot of science development that could slow an engineering project aimed at real machinery.

National Lab Perspective

John Grossenbacher, the Director of Idaho National Laboratory, explained that his facility is a government owned, contractor operated laboratory and that his employer, the current contractor, is the Battelle Energy Alliance a non-profit coalition lead by Battelle that includes Babcock & Wilcox, Washington Group International, the Electric Power Research Institute, and an alliance of university collaborators. The university portion of the alliance is a national university consortium led by MIT and includes such nuclear engineering universities as New Mexico, North Carolina State, Ohio State, and Oregon State as well as a regional collaboration with the major Idaho universities-Boise State, Idaho State, and the University of Idaho. (Actually, he did not list all of those universities and member organizations, I got that information from the press release linked above to the words “Battelle Energy Alliance”.)

Aside: Vice Admiral John Grossenbacher was the head of the US Navy submarine force for about three years before he retired. He is a man with deep experience in leading large, complex technically demanding organizations. He is a very smart and well respected man, but his perspective on entrepreneurial activity and mine are rather different. He does have some great ideas about used nuclear fuel, though. End Aside.

As Mr. Grossenbacher described, NGNP is a public-private partnership where the government’s role is to lay the foundation for the industrial development that will be the responsibility of the private partners. NGNP has already invested about four years in turning the “art” of making TRISO particles into a repeatable process that that can reliably produce fuel that is demonstrating superior results in its test runs in the high flux test facility. He mentioned that the testing has reached the point where fuel particles are achieving 16% burn-up without failure.

To provide some perspective, most light water fuels are only licensed to achieve about 5% burn-up. Because of the potential that further use might lead to excessive gas pressure inside the long thin tubes used to contain conventional reactor fuels, there are strict limits to how long fuel users can leave the fuel in the reactor before they have to remove it and store it. Moving from 5% to 16% burn-up is huge in terms of stretching the life of each fuel load and there is still room for improvement. Increased burn-up allows plant owners to reduce both the material inputs and the outputs that require long term storage. Improving burn-up is a good thing for plant operators and customers. It is not as beneficial for the fuel producers who want to sell more fuel.

Besides the material science part of developing and demonstrating repeatable fuel processes, the other major portion of the government’s planned contribution is to pave the licensing path. As Mr. Grossenbacher described, the current NRC processes and rules are all focused on light water reactors. All of the NRC license reviewers have that as their entering argument, but the NGNP program is working with the NRC to establish the modeling codes required for licensing facilities with a different basis for safety analysis. The rules will still be stringent and protect the public, but they will, by necessity, be different than the ones that apply to light water reactors with steam plant secondary systems.

This licensing process appears to be the very long part of the projected timeline – again, the NGNP has the goal of being operational with a “commercial scale” facility in 2021, about a dozen years from now.

After the talks, there was a short question and answer period. (The session was scheduled for an hour and started about 15 minutes late, so there was not as much time as I would have liked for questions.)

Questioning Attitude

As is my annoying habit, I had my hand in the air within seconds after Jack Spencer of the Heritage Foundation asked if there were any questions. I asked John Grossenbacher what the NGNP could do to catch up to the Chinese HTR-10, which is a high temperature gas reactor that has been operating since about 2003. His answer was that he did not think that we needed to catch up to that “laboratory scale” reactor; we had already done enough proof of concept work to move directly to something that was commercially viable. (Sorry John, if my paraphrase is not exactly correct, I forgot my recorder and did not take notes.)

I then followed that by asking what are we going to do t

o catch up after the Chinese have completed the 250 MWe high temperature gas reactors that have already broken ground and should be operational by 2013 or 2014. Grossenbacher’s response was that those reactors are still just focused on producing electricity, not on process heat. If that was my standard then he guessed that we would not be catching up.

After the Q&A session, I had the opportunity to talk with Fred Moore for several minutes to find out more about what his company considers to be a commercially viable size for a process heat source/power plant. (Remember, chemical plants need both, not just heat and not just electricity. They are some of the largest users of cogeneration systems where the heat left over after the turbines can be used for the process heat addition.)

Moore told me that his company normally designs their facilities to be able to keep operating at full capacity even with the loss of their single largest cogeneration unit. They are all connected to the electrical power grid, so if they loose a unit that is supplying both heat and electricity, they can purchase more electricity from the grid and direct their other operating cogeneration units to supply enough heat to make up for the supply that was lost. That puts the size of the largest units to something like 400-500 MW thermal. As I might have guessed, NGNP is planning to build something right at that maximum size to take advantage of “the economy of scale”.

I asked Mr. Moore if his company considered a 100 MWth or even a 50 MWth machine to be commercially useful. He did not really answer, saying that he had not really thought about that and figured that others in the NGNP Alliance knew more than he did about the complications of building smaller power plants.

The value of doing

My perspective on this project is colored by my three years as a manufacturing company general manager. It was an intensive period of learning; it was a small enough company to allow (demand) that the GM handle a wide variety of tasks without much staff. We had both high volume production products with runs in the hundreds of thousands and even millions of units and we also did custom work and new product development with production runs in the low single digits for prototyping.

Among many other lessons learned by fire, I learned that there is still a lot of learning involved in moving from knowing exactly how to make a few carefully crafted items and making a high volume, competitively priced product with strict quality standards in markets where the competition has faster machines, larger purchase volumes and/or access to very low wage workers.

Aside: J&M Industries was a profitable single owner company in the late 1990s making plastic toys, boat parts, kitchen trinkets and single use medical supplies in the USA with workers who made a bit better money than the average for our area. Most of our competition was from China or from well-capitalized companies with much larger market influence. End Aside.

My food for thought for any NGNP influencer who might read this – please recognize that there is a lot to be learned by actually making ever larger volumes of fuel and actually operating that fuel at temperature and pressure in very similar environments to those that will be used in the large machines that you envision. Light water reactors did not go directly to 1600 MW or even to 1000 MW. They started out as power plants for submarines and proved out many of the material issues at a much lower size and higher unit volume than would have been possible if people had decided that they needed to build machines to compete with coal plants first. By the time that plants like Oyster Creek were being ordered by utilities, dozens of submarines were in operation with documented history that could be used by the manufacturers to ensure confidence that they knew most of the issues they would face.

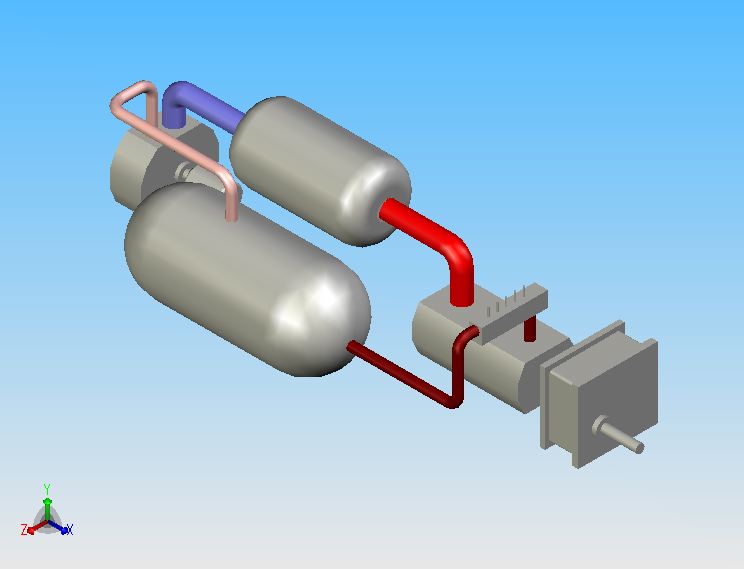

Of course, that food for thought is really quite selfish. I would love for Adams Atomic Engines, Inc. to be invited into the NGNP club to show them that there are lucrative markets where decision makers think of plants that can supply 400-500 MW thermal as being WAY too large to be interesting. I would also love to show them that operating “demonstration” units has a huge marketing value – smart buyers of large, complex machinery look right past a PowerPoint, brochure, or graphic simulation and say “Show me”.

I want to thank Jack Spencer, Josh Freed and their respective organizations, The Heritage Foundation and Third Way, for hosting this talk. The crowd at Rayburn House Office Building was refreshingly large and interested in learning more about generating massive amount of clean fission energy for something in addition to electricity production.

I’ll close with more ideas – they are really flowing right now.

A terrific application for several heaters that can produce 400 MW thermal at about 800 C is to replace similar sized boilers at coal fired power plants. Like Jim Holm, I think that Coal2Nuclear is the best way to make use of the investment at existing coal fired facilities for items like steam plants, electrical distribution, and cooling water. I think the conversion would be a heck of a lot cheaper than trying to install the chemical facilities and plumbing required to capture and sequester CO2. Preventing pollution is often cheaper than trying to cure it.

Lest people in the coal industry take offense at loosing their customer base, they might want to go back and talk to Mr. Moore at Dow. He spent quite a bit of time talking about how a combination of abundant heat, water and any abundant source of carbon can be combined to produce an amazing variety of chemicals that can make almost anything. Chemical plants with HTGRs next to coal mines would enable a lot more employment in coal producing areas. It would also allow them to send out much more valuable product lines than uncovered rail cars full of raw coal at $40-100 per ton. Heck, they might even be able to break the hold of the railroads by building pipelines to carry out the finished products.

If only I could figure out how to make the rail roads healthier – hmm. Perhaps they could move up scale from high volume shipments of cheap coal to high-value passenger transportation. I am sure that you have ideas worth contributing. It is a lot more fun that reading today’s Wall Street Journal and finding out that another 651,000 people lost their jobs in the USA last month. How can people be losing their jobs when there is so much work to do to make this world a better place for our children?

PS – after writing that last sentence, I stepped outside in my bare feet to pick up the morning paper. The sun is just rising so the view from my front porch showed a sky with a beautiful shade of orangey red. There are a few remnants left of Monday’s snow storm, but the weather man is predicting that it will be in the mid 70s (F) today. As I predicted, however, the bold headlines on the Wall Street Journal say:

Jobless Rate Tops 8%, Highest in 26 Years

I sure hope that the people who fought to prevent the US government from enabling a $50 billion private investment in new nuclear power plants through loan guarantees are proud. I wonder where they think that money would have gone if not into the pockets of tens of thousands of American workers. I also wonder if they realize just how much future prosperity will be enabled when new nuclear plants do start operating and producing massive amounts of clean energy.