Amy Chua Would Make a Terrific Nuclear Power School Instructor

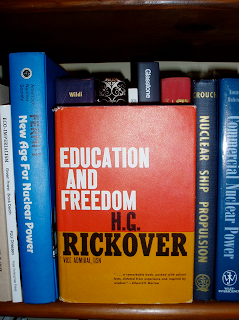

A bit more than 50 years ago, Hyman G. Rickover published a book with a prescription for America’s educational system titled Education and Freedom. In that book, Rickover shared some of his thoughts about the importance of high standards, enabling students with facts, and the benefits that entire nations gain when people achieve mastery of difficult topics.

Having been trained in the focused nuclear education system that Rickover established, I am pretty sure that he and Amy Chua, the author of Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother would have gotten along rather well. In fact, I think he would have welcomed her as an instructor at his Nuclear Power School and asked her to teach her colleagues how to extract excellence from their students.

Based on relatively recent contact with the Navy’s Nuclear Power School, I am quite certain that it remains true to Rickover’s standards as a tough place where standards of accuracy and performance remain unbowed by curves. The bar there is high; students work hard and most prove that they are able to master the difficult, but important topics. One thing that has always been a part of the nuclear power training pipeline is a lot of closed book tests that are NOT multiple choice or easy to grade.

After a year-long training program that is about as pleasant as drinking from a fire hose, about 70-80% of the carefully selected students walk confidently across the stage and enter into a field where continued study and improvement is the accepted norm. From what I know of the equivalent training program in the commercial nuclear industry, the standards there are just as high. The training program graduates and license holders are just as enabled by facts that they stuff into their brains. The material is not easy and the number of people who are willing to go through the difficult process of learning it is rather limited.

However, like learning to play a challenging piece on a violin, or learning how to perform a challenging surgical procedure, the effort to understand nuclear technology is worth the occasionally painful struggle. The people who master the subject can make great contributions to society by helping to maintain the system that is arguably the equivalent of the cardiopulmonary system of an industrial society – its reliable power grid.

There are, of course, somewhat simpler and more readily understood technologies that perform a pale imitation of the same function as a high-performing nuclear power system. Nearly anyone can understand how a wind turbine works and anyone can put a solar panel on their roof. It is also easier to learn to strum cords on a guitar than to play a concert quality violin.

There is little doubt in my mind that the high standards of performance and achievement demanded of the people who work in the nuclear industry have contributed to the rather incredible record of safety and plant performance. Though it is possible to find many negative stories about leaks, spills, and equipment failures, the facts speak for themselves. Few industrial injuries, no public safety impacts in more than fifty years, a decade worth of average capacity factors in the low 90% range, and unplanned shutdowns per unit in the low single digits each year. Most of the negative stories make the news for the same reason that editors are more likely to publish a story about a man biting a dog than about a dog biting a man. Routine excellence is not newsworthy.

I have no doubt that the incredibly high standards have done nothing to help the popularity of the power source. Quite frankly, Rickover’s prescription for educational excellence was ignored by most. Amy Chua’s description of her own efforts to arm her children with the power of knowledge have not won her universal acclaim. From my experience in the Navy, I can tell you that there are plenty of strong, proud leaders who remain resentful of having been rejected by nuclear power school recruiters or sent packing from nuclear power school because they failed to invest the hard work in class to learn what they needed to know.

It is also pretty obvious to me that some of the decision makers at electric power utilities prefer a less technically demanding power source, one that can be easily installed and operated without too much fuss. The decision makers especially like those less demanding power sources when they have figured out ways to make the public bear the brunt of the additional environmental and reliability costs they impose or the additional risks of fuel price volatility included in something like burning vast quantities of natural gas.

Though most of my nuclear industry colleagues are quite pleasant once you get to know them, they do have a tendency to see things in black and white. They expect people to work hard, to be able to answer hard questions, and to know when they need to do some homework before trying to fake their way through a difficult test. That does not always make them the best salesmen and it does not endear them to people who spend their college years in the liberal arts buildings or debating unanswerable questions about the meaning of life with great vigor in coffee shops and fraternity houses.

The rare world view of people like Rickover and Chua can be seen as a threat – some people in influential positions believe that social achievement and study by committee is somehow more important than getting facts right. In fact, those underachievers can be downright insulting – David Brooks called Ms. Chua a “wimp” because she did not allow her daughters to participate in sleepovers.

Managing status rivalries, negotiating group dynamics, understanding social norms, navigating the distinction between self and group — these and other social tests impose cognitive demands that blow away any intense tutoring session or a class at Yale.

Yet mastering these arduous skills is at the very essence of achievement. Most people work in groups. We do this because groups are much more efficient at solving problems than individuals (swimmers are often motivated to have their best times as part of relay teams, not in individual events). Moreover, the performance of a group does not correlate well with the average I.Q. of the group or even with the I.Q.’s of the smartest members.

Aside: As a long time competitive swimmer, I have to challenge Brooks’s example. Swimmers may be able to achieve better times in relays, but that is only because they can use some anticipation techniques that are not available from a “flat start”. Each swimmer in a relay is completely independent and must have individually prepared for the event. That is one disagreement that I have with Amy Chua and Admiral Rickover; I think mastering a challenging sport can be an achievement worth the investment of time. End Aside.

Somehow, nuclear advocates need to help people like Mr. Brooks understand that committees make lousy nuclear power plant operators and machinery designed by committee rarely functions with precision. We need to help him understand that not everyone can be a nuke or operate a po

wer grid, but that is okay. He and everyone else who wants the freedom enabled by having clean, reliable electricity whenever and wherever they need it should turn those decisions to specialists who are willing to work hard, master their subject, and use the best possible technology. The measure of “best” should never be “easiest”, “quickest”, or “cheapest” over the short term.

Postscript: When Admiral Rickover interviewed me for his program, the engagement was mercifully short. He asked me, “Why are you an English major?” I told him that I liked to read and write. His next question was “Read and write? Have you written any books? I have written three. Have you read any of them?” My answer was “Not yet, sir.”

As a submarine Engineer Officer, I read a collection of his letters to commanding officers from cover to cover. I keep “Education and Freedom” on my shelf and refer to it fairly regularly. I guess I am just keeping my implied promise to the man, even 30 years after that interview.

I wonder if Amy Chua’s daughters are looking for employment. They would be terrific senior reactor operator candidates.

While I agree that with a nuclear reactor operator you want people to be perfect (via hard work), raising a child to be perfect via hard work is a recipe for a dysfunctional personality and a huge therapy bill.

@Tony – I do not think there is any mention of the word “perfect” in my commentary. The idea is that striving for excellence and mastery of a subject is worth the effort. Though it might be too early to tell, neither one of my adult daughters have spent any time in therapy and both turned in rather “boring” monochromatic (essentially single grade) report cards through their entire educational history.

I think they even still like my wife and me.

No, perfect is the enemy of good.

If your design has to rely on your people being perfect, then it is a very poor design.

My thought on hearing about Amy Chua was “I hate to think what would happen if two such mothers had children in the same class…”

LOL

@George – having two (or ten) students with “tiger mothers” in the same class might be a bit of a challenge, but imagine the benefits that might accrue if some of the techniques that Ms. Chua uses were employed by a “tiger teacher.”

Part of my fascination with her book – which I am now reading – is her deep respect for the resilience and capacity of the human mind. I may be publishing a post today on the contrast in current American society between adulation and rewards given to sports coaches who expect sacrifices and hard work from athletes and our relative lack of similar rewards for teachers that demand sacrifices and hard work from math and science students.

Has it been said that a giraffe is an animal designed by committee?

Committees have their place, just as individuals striving for excellent have their place. Not sure where David Brooks’ excellence is.

While there were other auto manufacturers before Mr. Ford – all producing practically bespoke cars with arguably far more “excellence” in design and “craftsmanship” than the Model T – requiring “excellence” in technical skills to operate and maintain them – they did not make the sort of impact that Mr. Ford did.

Mr. Ford produced simple cars that ran good enough at an affordable price, and he produced a tremendous amount of them. Through mass production, he brought down prices enough that most American families could afford one. Admittedly, they weren’t exactly models of “excellence”, but they worked decently. And they didn’t cost much, unlike the original cars made by those talented “craftsmanly” manufacturers. Mr. Ford became rich; the “craftsmen” either changed their ways or went out of business.

The moral of this story: quantity has a quality all its own; an insistence on “craftsmanly” “excellence” that prevents the widespread dissemination of a technology arguably hinders its development far more than attempting to dumb it down to a reasonable level, make it simple and idiot-proof, and distribute it as widely as possible.

What I found most inspiring about the Adams Atomic Engine is that it does not require the same level of “excellence” in facilities, operations, or personnel that large scale LWRs do. It does not need to have expensive, active safety systems, or an expensive containment, and, assuming it has a sufficiently user-friendly interface, it probably does not require extremely skilled personnel to operate it. It’s practically pour, plop, plug, and play. And it probably can be fabricated in mass production.

It’s kind of like one of those not-so-excellent Model Ts – it works and it probably can be made very cheap. And that’s why it has an “excellence” all its own.

@Dave – As evidenced by my effort to develop Adams Engines, I once thought about the future of nuclear energy as being aimed at just the kind of simplification and mass market appeal as you are describing. My model was the personal computer (and now handheld computer) accessible to almost anyone.

My thinking has evolved. I still think that there may be a day in the future where such a model is possible for nuclear energy, but we are at least a full generation away from that. In essence, nuclear energy is still at the stage of mainframe computing before there were timesharing terminals. The number of people who are completely comfortable with the technology because of daily contact and routine lessons learned is still an incredibly tiny slice of the population. We do not have enough of them to provide the teachers for a move to broad accessibility.

Before we can ever get to a time of “personal” nukes, we have to move through a stage of “mini”, not “micro” nukes. We need to have a whole generation where the number of people who work with the technology on a daily basis steadily increases so that those people can spread knowledge broadly.

Though some children born today may take personal computing for granted, there really was a very long process of broadening and teaching quite complicated subjects with enough repetition so as to allow human minds to begin to think of those topics as so simple that “everyone knows that”.

It also took a whole lot of people inspired by demanding task masters like Steve Jobs and Bill Gates working hard behind the scenes to develop the technologies that made really complicated tasks and connectors seem so simple as to be almost trivial. Having struggled to learn a bit about how computers, networks, user interfaces and microprocessors work, I will testify that those technologies are not inherently simple and did not evolve through magic, but through a LOT of hard (rewarding and well-compensated) human intellectual effort.

What you’re saying is true. We’re still in the IBM 704 stage of nuclear power.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IBM_704

We need to get to the IBM 360 stage before getting to the PDP-11 or the Apple II stage.

Of course, it would be nice to see Moore’s Law take effect sometime soon.

111

I successfuly went through the program in the early eighties. Then it was tough. 1/3 attitrition rate was the rule of the day. I have recently worked at the prototype in Charleston, S.C. for three years as a civilian contractor. For the most part, the kids that go through now are taken by the hand and walked through the whole program. The Navy has been bombarded with so many law suits because “little Johnny” failed out of the program, that the academic attitrition is almost zero. Used to be you had to be in the top 10% to get ELT (Engineering Laboraroy Tech) school at the end of prototype. Now they just take volunteers. I’m pretty sure Rickover would be greatly disappointed to see how the Navy has lowered its standards in the face of political correctness.

My comment, I suppose, doesn’t fit with the post very well, but neither does the one above.

Just first impression, this guy “dre” sounds like he’s full of horsehockey. Yeah, the ELT NEC is/was voluntary, but they didn’t ask if you wanted it unless they thought you were suited. AFAIK, there is no 10% cutoff. I’d like confirmation from a contemporary source (I was in class 8304).

Now they just take volunteers. That’s a less-than-clever attempt at distortion that illustrates how the way you say something reveals a sinister agenda. (Kind of like denigrating “C-students” who were so, before learning of their greater potential under proper motivation– thanks, Navy, in my case.)

As for “…the Navy has lowered its standards in the face of political correctness.” That would be only due to orders from civvy leadership.

Sheesh– what does that mean: “They just take volunteers.” US military’s been all volunteer (with slight incentive of pay) since ~1973.

The SEALS– they just take volunteers.

ROTC– they just take volunteers.

Navy Nukes– man, that’s some dangerous work (ha! comparitively)– they just take volunteers.

USNA– they just take volunteers!

@Reese – I hope that you do not think that my recent commentary about ‘A’ students versus ‘F’ students was a denigration of ‘C’ students who figured out later in life that performing well in hard classes was important and worth the effort.

I do have little respect for what I refer to as “proud C students” who never do figure out that they can do a lot better than that with, as you say, proper motivation.

With regard to dre’s comment, there is, sadly, a bit of truth to the assertion that the Navy’s once incredibly impressive technical training programs have been harmed in recent years. I do not ascribe that to “political correctness” so much as misplaced budgetary analysis by people who think they can save money by shorting investment in people. I was in the trenches of that analysis, and fought it with every tool at the disposal of a mere staff O5, but there were people who pointed out to budget constrained O7’s and O8’s that if they could just slice a few weeks off of A school and perhaps cut C school opportunities they could get rid of 1200 instructor billets and save a few tens of millions per year.

Then they had a few software salesmen with forked tongues telling them that self paced, computer based training could replace even more instructors.

I will say that NR was probably the most successful organization in resisting the implementation of the reductions, but they did experience some degradation in resources.

Of course, the long term result of those budgetary measures has been a less ready fleet that requires more maintenance. Pay me now or pay me later. I hope that things are turning around; there has been some well publicized recognition of the stupidity of the Reduction in Training. http://www.navytimes.com/news/2010/12/navy-insurvs-122010w/

I was not the only one who recognized what was happening, though I was one of the most vocal. In the eyes of at least one three star who is now a four star, I was one of his least favorite staff members because I inconveniently pointed out that his decisions were dangerous. The revenge is that he is now the guy who has to operate the fleet that is being manned by the people trained in the system he was willing to decimate to free up a little bit of cash.

(The salesmen actually branded it as the “Revolution in Training”, but I use my own choice of words to describe what really happened.)

@Mr. Adams, guest in his own house,

From the A-F post, which BTW was a swell analogy (or metaphor– I don’t know– you’re the Lit major): “I have admitted this before; unlike a certain former president who was a proud ‘C’ student who gained a position of responsibility through popularity, I was a curve breaking geek throughout my academic career.”

Sorry, I took that as a sarcastic jab at President Bush, “proud” being the sarcasm-enabling word, like he actually should be ashamed. Usually your Liberal angle is more subdued in your posts, so I was suprised to see a tired, throwaway line about the “dullard.” Literalness and sarcasm are often misdiagnosed in Internet text, as I’m sure you know in your decades-long history on the medium. I think he was quite humble, yet confident when he needed to be, and sometimes when he ought not have been. Perhaps that’s what you meant, that even a C-student could rise to the job.

The rest of your reply is a little sad, comparable to the sadness that all the CGNs were cut up (to save money short term, I believe). I will have to moderate (carefully) my automatic endorsement for any Navy Nuke who comes my way looking for a position. Apparently it shouldn’t have the weight I’ve convinced my coworkers it does.

@Reese – sometimes it is prudent to make it slightly difficult for search engines to match names to comments made in public forums.

Yes, you did correctly interpret my jab. That proud ‘C’ student was the guy who hired the budget decision makers who bought into the idea that training was a good place to cut budgets. I have less direct experience with the decision processes in the formerly excellent technical training programs in sister services, but I am quite sure that the guidance for slicing instructors was coming from somewhere above the rank of my 3 star boss and most likely above the rank of the 4 star CNO named Clark who came up with the brilliant idea to institute a reduction in training under the brand name of a “revolution in training”. I may be misremembering, but as I recall there was some defense of the ‘C’ student as one who did slightly better in his MBA program. That is a course of study that often teaches people how to make more money by cutting the cost side of the equation while assuming that the revenue side will not fall as fast. I hate that kind of misuse of math.

The humility might have been there, but so was the arrogance that engaged us in someone else’s fights and cost the country in excess of a trillion (and still growing) plus the lives of thousands and the health (physical and emotional) of tens of thousands.

A more humble man who worked harder in school to really understand what makes the world go around would have been a less damaging choice.

By the way, I am not proud to say that I voted for the man the first time around. I am pretty sure that I was convinced by the fact that he had a good name. I should have known that heredity has been proven to be a terrible way to pass on leadership roles.

Eh, don’t feel bad, Rod. The other guy was a “C” student too … and a drop-out to boot.

@Reese – one more thing – you can still safely recommend Navy Nukes. As I said, NR was pretty successful in stiff arming the reduction in training. Any unavoidable effect from a slight reduction during shared ‘A’ schools was made up during nuke school, prototype and fleet experience.