One vignette in radiation fear campaign

Abject fear of radiation, even at low doses, is a root cause of the cost and schedule difficulties associated with atomic energy development and deployment.

At Atomic Insights, we believe that most of the fear of low dose radiation is not only unwarranted, but it is also purposely created, taught and carefully reinforced by people.

Every person that participates in the campaign has their own unique combination of motives and techniques, but some of the major factors are a desire to prevent use of nuclear weapons, a desire to eliminate nuclear weapons completely, a desire to discourage nuclear energy development for competitive reasons, and a desire to discourage use of moderate doses of radiation as a treatment or a cure for various health conditions.

The radiation fear campaign has been going on in earnest since June 13, 1956. That was the date when the New York Times ran a front page headline stating that “SCIENTISTS TERM RADIATION A PERIL TO THE FUTURE OF MAN.”

Throughout the decades since that first proclamation was issued, there have been additional claims and stories with fear creation and maintenance as either a sole or ancillary purpose.

Here’s a sample from the campaign.

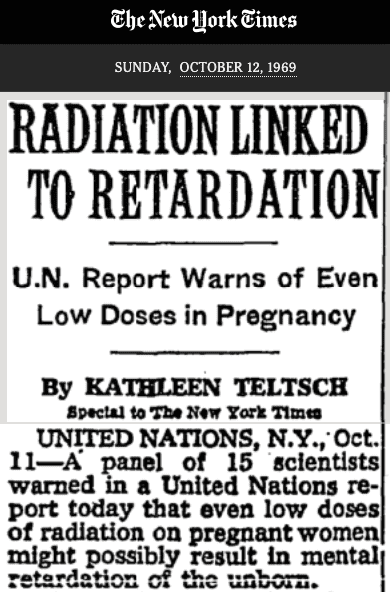

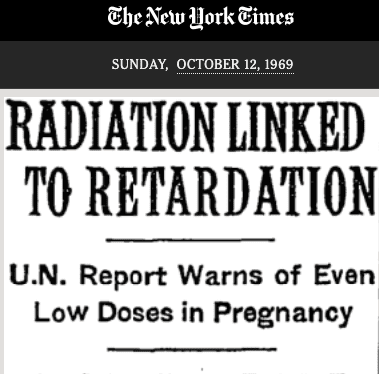

On October 12, 1969, the New York Times published an article written by Kathleen Teltsch under the following headline: “RADIATION LINKED TO RETARDATION: U.N. Report Warns of Even Low Doses in Pregnancy.”

That is a headline that can capture attention and a subtitle that stokes fear, especially among young women who are planning to have children. It will cause fear, anxiety and guilt among young mothers that have, for one reason or another, been exposed to radiation while pregnant with children that are still growing.

It is an unfortunately truth about newspaper readers that some finite portion of the audience only reads or remembers headlines and subtitles.

But there is more to the story.

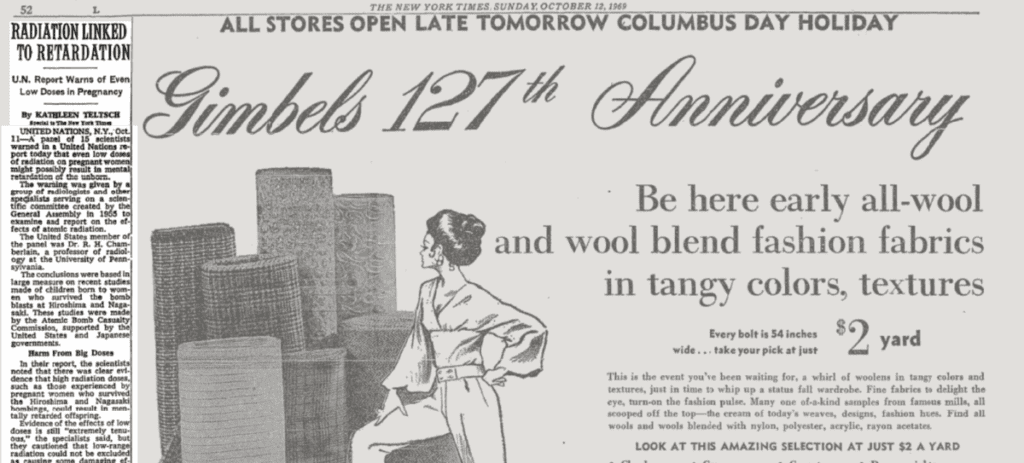

Though this article did not make it to the influential front page, the editors carefully chose a placement that was almost as impactful.

It was a full, single column article running from top to bottom of the left-most column on a page that was otherwise filled with an attractive ad for the Gimble’s 127th Annual Columbus Day Sale. October 12, 1969 was a Sunday, so the sale was happening the next day.

It seems likely that the article and its placement would draw people in the exact demographic that might be most interested in – and frightened by – finding out that radiation harms children in the womb.

I’m not a newspaper skimmer lazily flipping through sale ads on a Sunday morning of a three day weekend in the late 1960s, so I carefully read the rest of the article. I wanted to learn more about what the New York Times and the United Nations wanted to tell people about radiation health effects in the fall of 1969.

The scientists that wrote the report issued in October 1969 were members of the standing committee that the United Nations had created in 1955 to study effects of atomic radiation. The primary source for their reports was data gathered by the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission, which studied effects of the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

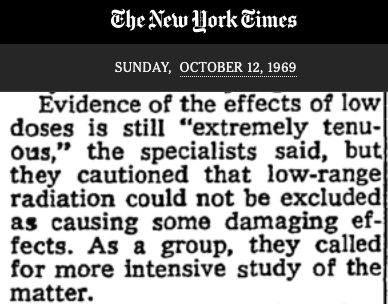

Though the article subtitle gives the impression that even low doses were found to be harmful, the article states that the specialists who wrote the report found that evidence of harm at low doses was “extremely tenuous” but harm could not be “excluded.”

By their definition, any dose less than 50 roentgens was considered to be low. The article reminds readers that a typical diagnostic X-ray would give a dose of 1 R or less, but also tells them that doses have been gradually lowered through technological improvements. Some readers who might have had X-rays while pregnant in the past are left wondering if they might have received higher doses.

The article did not mention that 50 R was 10 times the maximum allowed annual dose for trained radiation workers at a nuclear power plant. It substantially exceeded the amount of radiation that any member of the public might expect to receive, even if accumulated over a lifetime living at the fence line of a power plant.

The report was based on studying development of 1,613 children whose mothers were pregnant at the time of the atomic bombings.

Researchers binned the victims based on the calculated doses the mothers received from the explosion and its aftermath. It’s worth noting that virtually all of the radiation received was instantaneous. Those who received higher doses were highly likely to have been subjected to additional bomb effects including blast and heat.

Though there was a strong correlation between mental retardation and radiation doses above 200 R, the correlation was much lower at doses between 50 and 99 R. Below 50 R, the incidence of retardation was less than 1%.

There is no evidence presented indicating that the incidence of retardation among children exposed to less than 50 R is any different from the level that might be found any any randomly selected population.

Though the article provides accurate information that should be reassuring to anyone with critical reading skills, it was headlined, placed and structured in a way that creates fear and uncertainty.

In the emotionally charged topic of child development and the responsibility of mothers to provide protection, it provides reason to fear radiation – even at low doses – when there is no evidence indicating that fear is the correct response.

Of course, the editors at the New York Times didn’t create the report, and Ms. Teltsch probably didn’t write the headline, but both helped make this an effective component of the long-running campaign.

The article concludes with some hints about why the report was issued and why the Times chose to cover it in a way that would capture attention and perhaps stimulate action.

Even though the US, the UK and the Soviet Union had agreed to stop testing nuclear weapons in the open atmosphere by 1963, both France and Communist China were still engaged in atmospheric testing programs that still released uncontrolled fallout.

Underground testing was still seen to be somewhat risky because test sites still leaked.

Not stated in this article – but known to contemporary readers – is the fact that there were dozens of nuclear power plants under construction in the United States.

Though begun during a period of optimism about atomic energy and its potential for benefiting electricity customers, there was a growing level of concern about health effects of radiation from routine operation of those plants. People concerned about those effects were making their concerns known through active efforts to slow nuclear plant construction and add increasing layers of protection.

History students can also find numerous indications that the coal, oil, gas, freight and banking industries had always been worried about losing sales to nuclear power.

It’s not difficult to understand that they would be happy to buy ads in newspapers that published stories that might slow their atomic competitor.

“coal, oil, gas, freight and banking industries”

The first three have obvious motivation. Freight becomes obvious as soon as you think about how much fossil fuel is moved around by the freight industry.

Please explain why the banking industry would have a motive to oppose nuclear?

Love the ‘Radiation linked to retardation’ clipping… was that paid for by the Leaded Gasoline Alliance?

It’s amazing how triggered people are by fear. Fear of coronavirus, fear of radiation…. very few fear big government. People have ‘faith’ that things like radiation and covid are out there, waiting to kill them. If they had faith in something else, something thousands of years old, people would have less fear of these ‘deadly’ things. They would be at peace.

@James R. Baerg

The fossil fuel business is highly capital intensive. One of the reasons for Rockefeller’s huge success was his recognition of the importance of developing deep ties to the banking industry in the form of lots of borrowing even when times were good.

Banks holding massive quantities of “paper” from an industry have an interest in helping that industry succeed and defend itself from new competition. Yes, not all banks, and yes, some banks might even be more interested in lending money to a new industry. But new lending is generally less important than ensuring that the loans that are already outstanding get paid back.

By the time the third generation of Rockefellers came along (John D. III, Nelson, Laurence, Winthrod and David) the ties to banking including ensuring at least one of them went into the business and rose to be a leader in the industry. (David)

Why do you think the World Bank and other multinational development lenders have policies that either prevent or strongly restrict their ability to lend to nuclear projects? The World Bank has made exactly one loan to nuclear and that was to a 1950s era Italian project.

“very few fear big government”

Oh really?

There does seem to be an irrational tendency for some people to fear big corporations & others to fear big government, rather than for everyone to regard both with suspicion as having the ability to do great harm as well as some good.

Indeed, there is a common line of fear of nuclear and fear of big government and big corporatism.

As if the cute little solar panels that are supposed to save the world are not produced by massive multi billion dollar profit minded corporations that produce their panels in low wage low environmental law countries to cut corners. As if big governments aren’t doling out billions of dollars in subsidies, tax breaks, feed-in-tariffs, must-take-power-even-when-there-is-no-demand-for-the-power regulations for these cute little solar panels.

What enables, or catalyses fear, seems to be a general lack of knowledge on the field of radiation and nuclear science, as well as the engineering actually involved.

Mainstream media are doing their darndest to obfuscate rather than elucidate. They never explain how a nuclear plant works, or what this so called waste is. They just extricate on how “dangerous” this stuff is – without explaining what scenario is supposed to vaporize these refractory fuel elements into a fine vapor to be inhaled by the public.

Most people don’t know a thing about radiation or nuclear engineering. Not the slightest. Most don’t even know that reactors are basically boilers. They are heat exchangers that make steam to drive a turbine to generate power.

Most people don’t know the difference between alpha or gamma radiation. Or even the difference between radiation and dose. Or even the difference between a toxic substance and a toxic dose. Tomorrow’s production of chlorine for bleach and other cleaning agents could kill the world’s population many times over. But it doesn’t because the chlorine doesn’t get into humans. Even though chlorine is very volatile, unlike spent nuclear fuel which is just a bunch of ceramic pellets in metal tubes.

People know essentially nothing that would be required to espouse a dogmatic opinion. Yet everyone has a dogmatic opinion on nuclear power. And the less they know, the more opinions they have.

I am convinced that a major key is just simple understanding of the basics. This will get people thinking. I’ve found that when people learn more they drop their opinions and start an amazing creative thinking process. All of a sudden they challenge their assumptions and beliefs. They start to question. They become scientists.

I’ve tried to do my part with a nuclear FAQ of sorts. Download it here.

If there is ever a part two to this article, perhaps the focus could be about the enormous difference in awareness and attention to the harmful effects and radioactive content of coal smoke and ash. JP McBride and others published a paper for Science magazine in Dec. 1978 detailing this difference. This received a mild revival some 10 years ago in SciAm.

Coal ash gets another pass by being virtually unregulated by the EPA. All things considered, the radiation exposure one may receive from coal burning is still going to be minimal, yet it is still at least “100x” more than any regularly running nuclear plant.

My hunch as to why there is hardly any awareness or outrage directed at coal and it’s radioactive pollution is that it’s just not “sexy”. The threat isn’t perceived as urgent or threatening enough to matter much.

Plus, coal is organic material; any radiation from it is therefore natural and quite different to the radiation from the nuclear plants.

/sarc

Big government is something to fear. There is a lot of historical precedent for big government not ending well (e.g. USSR).

What are your comments about the latest posting in the June 12, 2020 “Perspectives – viewpoint” section of World Nuclear News website about major oil and gas companies investing in new nuclear power projects?

scaryjello: There were 2 things wrong with the USSR. 1) Trying to run *everything* by the government 2) nothing like a real democracy.

If there had been real democratic control of the government. probably there would have been undoing of the many of the more disastrous policies like the collectivization of agriculture, if that policy could have been started in the 1st place.

There is reportedly a gender gap with regard to fear of radiation, however that doesn’t mean that all women have radio phobia. I bring this up because Joe Biden has pledged to choose a woman as his running mate. Perhaps you can come up with a list of women that it would be desirable to have as a VP. Given his age it’s likely that his running mate will become president if he’s elected.

A roentgen is an obsolete unit, about 10 mGy or 10 mSv in humans, so the doses quoted would not be considered low nowadays. Modern students can be reassured that modern x-rays are very much lower still, numbered in microsieverts.