Blast from the past from a “clean coal” advocate – Amory Lovins

One of the great ironies in today’s America is that a two time college drop out and Friends of the Earth campaigner who strongly advocated for increasing coal use is often held up as a hero of the environmental movement while also making a lot of money as a consultant for the natural gas industry, Wal-Mart and the Department of Defense. I am, of course, talking about Amory Lovins, the founder of the Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI).

It’s worthwhile to review the article that helped to launch Lovins’s career as a “consultant experimental physicist” – those are the words used in his blurb on RMI’s Staff List. His attention-getting article appeared the October 1976 issue of Foreign Affairs is still pointed to as one of the seminal thought pieces that helped launch alternative energy programs. It outlined an energy strategy choice between the “hard energy path” and the “soft energy path”.

I thought it might be fun to provide the world with an accessible copy of his description of coal technology from that article. It is also important to understand that Lovins and RMI still promote the strategies described in the article on their web site. This blurb is from their library page

For historical purposes many people asked that we re-release our 1977 paper, “Energy Strategy: The Road Not Taken?”. Unfortunately it is still very current, even though it has been out of print for decades. Where are America’s formal or de facto energy policies leading us? Where might we choose to go instead? How can we find out? Addressing these questions can reveal deeper questions — and a few answers — that are easy to grasp, yet rich in insight and in international relevance. This paper explores such basic concepts in energy strategy by outlining and contrasting two energy paths that the United States might follow over the next 50 years — long enough for the full implications of change to start to emerge. This article, by Amory B. Lovins, appeared in Foreign Affairs (www.foreignaffairs.org), October 1976, and is reprinted by kind permission of the publisher. Copyright 1976 by the Council on Foreign Relations, Inc. (November 1977).

Notice – there is not a hint of repudiation or revision in that description. Based on their own words, I would presume that the following still represents a part of the organizational view regarding future energy strategies.

Excerpted From Energy Strategy: The Road Not Taken?

Neglected for so many years, coal technology is now experiencing a virtual revolution. We are developing supercritical gas extraction, flash hydrogenation, flash pyrolysis, panel-bed filters and similar ways to use coal cleanly at essentially any scale and to cream off valuable liquids and gases as premium fuels before burning the rest. These methods largely avoid the costs, complexity, inflexibility, technical risks, long lead times, large scale, and tar formation of the traditional processes that now dominate our research.

Perhaps the most exciting current development is the so-called fluidized-bed system for burning coal (or virtually any other combustible material). Fluidized beds are simple, versatile devices that add the fuel a little at a time to a much larger mass of small, inert, redhot particles—sand or ceramic pellets—kept suspended as an agitated fluid by a stream of air continuously blown up through it from below. The efficiency of combustion, of other chemical reactions (such as sulfur removal), and of heat transfer is remarkably high because of the turbulent mixing and large surface area of the particles. Fluidized beds have long been used as chemical reactors and for burning trash, but are now ready to be commercially applied to raising steam and operating turbines. In one system currently available from Stal-Laval Turbin AB of Sweden, eight off-the-shelf 70-megawatt gas turbines powered by fluidized-bed combusters, together with district-heating networks and heat pumps, would heat as many houses as a $1 billion-plus coal gasification plant, but would use only two-fifths as much coal, cost a half to two-thirds as much to build, and burn more cleanly than a normal power station with the best modern scrubbers.

Fluidized-bed boilers and turbines can power giant industrial complexes, especially for cogeneration, and are relatively easy to backfit into old municipal power stations. Scaled down, a fluidized bed can be a tiny household device—clean, strikingly simple and flexible—that can replace an ordinary furnace or grate and can recover combustion heat with an efficiency over 80 percent. At medium scale, such technologies offer versatile boiler backfits and improve heat recovery in flues. With only minor modifications they can burn practically any fuel. It is essential to commercialize all these systems now—not to waste a decade on highly instrumented but noncommercial pilot plants constrained to a narrow, even obsolete design philosophy. (Energy Strategy pg. 12)

. . .

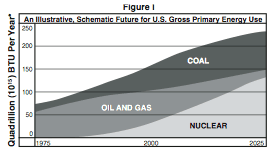

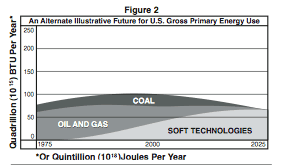

Properly used, coal, conservation, and soft technologies together can squeeze the “oil and gas” wedge in Figure 2 from both sides—so far that most of the frontier extraction and medium-term imports of oil and gas become unnecessary and our conventional resources are greatly stretched. Coal can fill the real gaps in our fuel economy with only a temporary and modest (less than twofold at peak) expansion of mining, not requiring the enormous infrastructure and social impacts implied by the scale of coal use in Figure 1.

In sum, Figure 2 outlines a prompt redirection of effort at the margin that lets us use fossil fuels intelligently to buy the time we need to change over to living on our energy income. The innovations required, both technical and social, compete directly and immediately with the incremental actions that constitute a hard energy path: fluidized beds vs.large coal gasification plants and coal-electric stations, efficient cars vs. offshore oil, roof insulation vs. Arctic gas, cogeneration vs. nuclear power. These two directions of development are mutually exclusive: the pattern of commitments of resources and time required for the hard energy path and the pervasive infrastructure which it accretes gradually make the soft path less and less attainable. That is, our two sets of choices compete not only in what they accomplish, but also in what they allow us to contemplate later. Figure 1 obscures this constriction of options, for it peers myopically forward, one power station at a time, extrapolating trend into destiny by self-fulfilling prophecy with no end clearly in sight. Figure 2, in contrast, works backward from a strategic goal, asks what we must do when in order to get there, and thus reveals the potential for a radically different path that would be invisible to anyone working forward in time by incremental ad-hocracy. (Energy Strategy pg. 12)

. . .

These choices may seem abstract, but they are sharp, imminent and practical. We stand at a crossroads: without decisive action our options will slip away. Delay in energy conservation lets wasteful use run on so far that the logistical problems of catching up become insuperable. Delay in widely deploying diverse soft technologies pushes them so far into the future that there is no longer a credible fossil-fuel bridge to them: they must be well under way before the worst part of the oil-and-gas decline. Delay in building the fossil-fuel bridge makes it too tenuous: what the sophisticated coal technologies can give us, in particular, will no longer mesh with our pattern of transitional needs as oil and gas dwindle. (Energy Strategy pg. 15)

For the record, here are the graphs of the “mutually exclusive

paths” recommended by Amory Lovins in October 1976 in a magazine published by the Council on Foreign Relations, just before the election of President Jimmy Carter. It might not have reached a broad audience, but I am sure that the article was carefully read by policy wonks inside the Washington Beltway.

Lovins’s Hard Energy Path

Lovins’s Soft Energy Path

When I get a chance, I will find the graph that I have somewhere in my files that would be figure 3 – the real energy path that was taken during the 30+ years since Lovins wrote the frequently referenced article that helped to define the energy policy actually followed.