Letter from the Editor: Delay Does not Indicate a Crisis

By nature, I am a procrastinator. I often live by the motto “Never do today that which you can put off until tomorrow.” In fact, I sometimes extend that idea to “Never do at all that which you can put off indefinitely.”

Some of my associates vehemently disagree with my way of thinking, but I often have been vindicated when someone decides to cancel a project that they have nearly completed or when God decides to make it rain right after they finish washing their car. As an example of my tendency, this letter is being written on day before it must be delivered to the printer.

It is my belief that procrastination may be the right answer to the current nuclear waste “crisis.” As usual, there are many who disagree and who chafe at inaction. In this case, however, inaction is cheaper, politically more acceptable and perhaps safer than frantically doing something, anything in frustration with the current situation.

Yucca Mountain

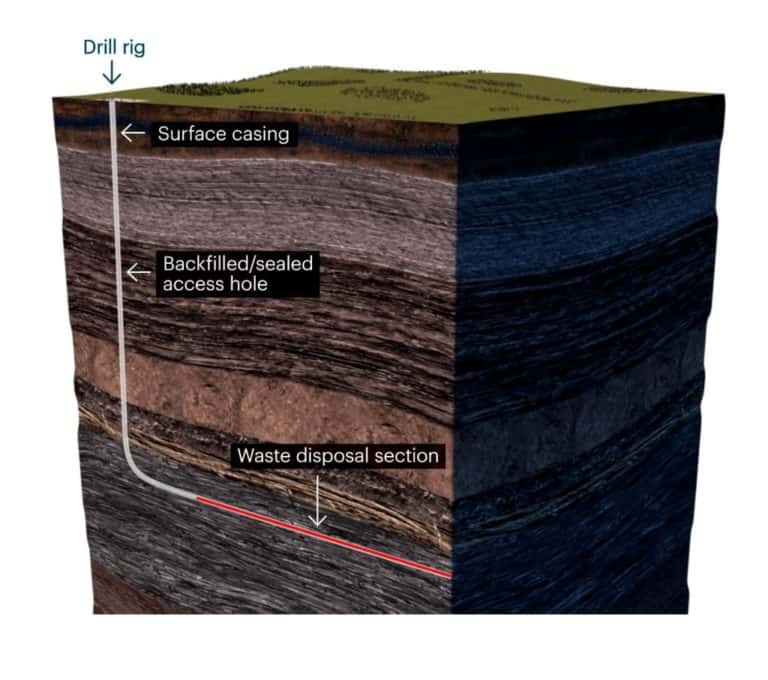

Yucca Mountain is a desolate place far from any human population center. It is a mountain made of very old and dry rocks that seems to have all the characteristics that one could desire as a permanent repository for material that people want to put out of sight and out of mind for a very long time. By law, it is currently the only place that is being investigated as the permanent storage location for spent nuclear fuel in the United States.

Unfortunately, the people who chose Yucca Mountain overlooked some key pieces of information. Partially because of their poor planning, the process of building the repository has slowed to a crawl despite the expenditure of several billion dollars. There appears to be little chance that the United States government will begin accepting nuclear waste by the 1998 deadline specified in the Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982 as amended in 1987.

The current impasse may be beneficial to the long term energy security of the United States and perhaps even the world.

Opposition to Construction

There is a significant body of organized opposition to the continued construction of the planned repository. Some of the members of the opposition question the site itself, saying that there is too much evidence of seismic activity in the local area. Others represent the official position of the State of Nevada, which believes that it has been unfairly singled out to be the sole recipient of a dubious honor.

Other members of the opposition attack any nuclear project. They have grasped the waste issue with the stated goal of constipating the nuclear industry in an attempt to halt its continued existence.

Still others have a libertarian opposition to the federal government taking responsibility for an industrial waste product. They believe that the private sector should handle the job.

Some of the transportation companies that will be asked to actually move the waste do not want the job. Their concern is that moving the material will put them in a no win situation that will hurt their existing business and put them at risk of severe financial loss in case of an accident.

Supporters of Yucca Mountain

There are some very active supporters of continuing progress on Yucca Mountain. Not surprisingly, the supportive group is led by utility companies that own and operate nuclear plants. This group’s trade association, the Nuclear Energy Institute, has made continuing progress on Yucca Mountain their top priority.

Allied with the utility companies are companies that build nuclear plants and those that specialize in administering government contracts for large projects.

The above groups have continued to make the case that the federal government has an obligation to begin accepting spent nuclear fuel by 1998 and that Yucca Mountain is the best hope for meeting this responsibility.

Mountain Out of a Molehill

Both the opposers of the project and the supporters are working hard to make the issue of spent nuclear fuel disposition more visible in hopes of obtaining a political decision in their favor. However, there is still plenty of time to decide the best approach to take.

The total mass of spent nuclear fuel in the United States is approximately 40,000 tons. This total only grows by approximately 4,000 tons per year. Though those numbers may sound a bit large, they need to be put into perspective.

A single coal power station producing 1000 MW of electrical power, approximately 1 percent of the power produced by nuclear generating stations in the U.S., will need to find a way to dispose of approximately 4,000 tons of solid waste every single day. From the point of view of the operating utility, the disposal of the 40,000 tons of gaseous waste that the coal plant inevitably produces each day is no problem at all. That deadly material simply goes up a tall stack where winds can disperse it all over the globe.

In contrast, every spent nuclear fuel rod is still exactly where it was put after it completed its tour of reactor plant duty. If needed, practically every gram can be accounted for and not one has escaped to do harm to human beings or other living creatures.

Commercial used nuclear fuel has been successfully stored above ground for nearly 40 years at a cost significantly lower than the billions planned for a permanent repository. There is every likelihood that this successful record can continue for an indefinite period.

If the waste is stored above ground for the next fifty years, perhaps it will provide time to think about ways to recycle the material instead of simply burying it to get it out of sight and mind.