Amory Lovins, the "Chief Scientist" who could not complete a degree program, is at it again

I finally am beginning to understand why I have such a different world view from Amory Lovins, the “Chief Scientist” of the Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI).

We have had completely different life experiences. In his 1977 book titled Soft Energy Paths on page 55, Lovins wrote, “In an electrical world, your lifeline comes not from an understanding neighborhood technology run by people you know who are at your own social level, but rather from an alien, remote and perhaps humiliatingly uncontrollable technology run by a far away bureaucratized, technical elite who have probably never heard of you.” In contrast, I grew up in a modest, solidly middle class house (the address was 6761 SW 10th Street, Pembroke Pines Fl 33023 if you care to look up the rest of the neighborhood on Google Earth) with a father who spent 35 years as an electrical engineer with Florida Power and Light.

(Note: Look for the fourth house from the left in the top row. It has a semi-circular driveway and no swimming pool. I lived there from 1962-1977; Mom sold the house in 2002 after living there for 40 years.)

Dad had a successful career and eventually supervised the transmission substation engineering group, but he was no alien, and certainly not an elite. He was definitely not remote, and I know he had heard of me. He was kind of technical, but still loved books, growing plants, talking with his kids, volunteering at church, serving as a official for swim meets, recycling rabbit poop, and taking his family on long camping trips. He also went to work one day per month in casual clothes so that he could participate in “storm training” (I remember those days clearly since they were the only days when we got to have breakfast together; he normally left really early to commute to work in FPL’s Miami office.)

When our South Florida region experienced one of its periodic storms, Dad would grab his hard hat and head out soon after the storm was over to help restore power as quickly as possible. I have always been very proud of what Dad did and believe that he and his colleagues – I knew a lot of them – were smart, good, well educated, admirable people providing a vital service to their neighbors.

During the summer of 1975, at about the time that Lovins must have been writing Soft Energy Paths, I participated in a church youth group mission trip to El Salavador where I learned in a very personal way what it was like to live in places where there was no electrical power grid. I watched people spending several hours per day collecting and carrying biomass on their heads so that they could cook a simple meal of rice, eggs and beans. I saw them start up their micro-power plants (aka diesel generators) when it got dark and carefully shut them down after a couple of hours of run time to conserve the already very expensive fuel. I saw how they handled normal human byproducts since they did not have running water or sewage systems since there was no electricity for running pumps.

Of course, there were parts of El Salvador where the conditions were very, very different and where people seemed incredibly wealthy. We thought at the time that the country was ripe for rebellion since there was such a huge gap between rich and poor. We were right.

Lovins overall view of electrical power’s place in the world and mine could not be more different. While researching this article, I was shocked to learn that Lovins and I do have something in common; his father was apparently also an electrical engineer. I cannot be sure, but my guess, from the rest of the context in which I learned that fact, is that Lovins’s father was a professor, not a practicing utility engineer. However, despite that tiny common thread, Lovins and I have taken significantly different educational and career paths.

Lovins attended Harvard for a year or so before dropping out to do some soul searching and mountaineering, and then moved to the UK to attend Oxford for a while during a period when the US had a military draft. (See The Hydrogen Powered Future) He did not graduate from there either. His mentor and hero was David Brower, founder of Friends of the Earth and he worked as the UK’s FOE campaigner for a number of years. He has written a lot of articles and some well publicized books. He travels around the world giving well attended speeches and collecting fees of up to $20,000 per talk. He now runs an institute that has an annual budget of close to 10 million dollars, much of which comes from consulting fees from Fortune 500 companies – including major oil companies – and the Department of Defense. He describes himself as a “consultant experimental physicist educated at Harvard and Oxford” and he is often billed as the “Chief Scientist” of the Rocky Mountain Institute.

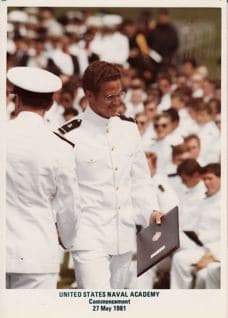

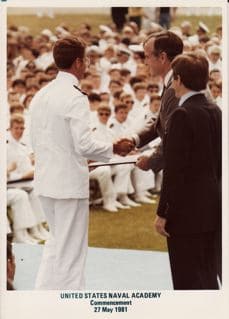

I attended the U. S. Naval Academy and graduated with a BS in English as what I call “the anchor honor graduate”.

(Aside: As a true believer in the Academy’s honor code, a more complete explanation is required. The top ten percent of a Naval Academy class gets the words “with distinction” written on their diploma. At the time that I graduated, that group also was the only one that shook the guest speaker’s hand and crossed the stage individually. I was 98 in a class with 973 students, but a mistake outside my control led me to get the “with distinction” notation on my diploma and provided me the opportunity to shake George H. W. Bush’s hand.)

After graduation I went through the Naval Nuclear Power Training Pipeline. I finished in the top ten percent of my nuke school class, slightly ahead of another English major who had been in my USNA company. For some reason, some of the more technically educated members of the class did not think much of being bested by a couple of “Bull majors”. I simply attribute it to the fact that the core curriculum that the Academy followed during the time when Rickover was still an active duty 4-star was well grounded in science, math, and engineering.

For the first 12 years of my professional career, I did some very practical work and learned a lot about what it takes to make machinery work reliably. I spent the next three years knocking on hundreds of doors, trying to raise the capital necessary to build a line of distributed, zero emission generators (see Adams Atomic Engines, Inc.) that were suitably sized for cogeneration. What I found was that many of the capitalists that I met were quite lazy and a bit greedy, they wanted quick, easy returns and they wanted me to do all of the work. I also found that many of the people who were developing successful projects using similar combustion technology were getting their financing from fuel suppliers. That is not very surprising, natural gas companies have massive capital bases and recognize that an installed base of gas turbines is an installed base of customers addicted to their product for the long haul. We seemed to be gaining traction in the early days of AAE, but falling gas prices eventually caused people to lose interest. We put the company to sleep in 1996.

I have spent the past 7 years working as a bureaucrat on the headquarters staff of an organization that employs about 600,000 people directly and an unmeasured number of contractors. Our annual budget is in the neighborhood of $127 Billion and we are one of the largest energy consumers in the federal government. We have also had aggressive energy conservation programs in place since the early 1970s.

Lovins continues to tell the world that energy con

servation is cheap and easy, that it, combined with “micro-power” (which really means diesel generators and natural gas fired combustion turbines), and traditional renewables (wind, solar, and biomass) make it possible to Forget Nuclear. He also believes that the investment trends of the past few years, where a large portion of the new power projects have been mandated and heavily subsidized wind or distributed natural gas plants indicate that capitalists have correctly determined that those are going to solve our energy problems. He believes that a massive increase in doing more with less – conservation – plus some not yet invented technology will allow us to live happy productive lives without using nuclear power.

I believe that cheap and easy solutions rarely work, that burning diesel fuel and natural gas – even with improved efficiency – is a high cost, high pollution way to produce electricity, that capitalists often have goals that do not match those of the rest of us, and that building well designed nuclear plants that can provide emission free nuclear power for 40, 60 or even 100 years is an good investment. Energy conservation is something that can only take you so far, there are diminishing returns that Lovins ignores completely in his assertion that it is cheaper than building new, modern power plants.

Lovins is flat out lying when he claims that nuclear power currently receives a government subsidy of “1-5 cents per kilowatt hour” and when he claims that the provisions of the Energy Policy Act will provide a taxpayer funded subsidy of “5-9 cents per kilowatt hour”. The US Energy Information Agency recently conducted a detailed study on current energy subsidies; even including national laboratory research and development that has nothing to do with current nuclear power plants, the total subsidy provided to nuclear power each year amounts to about 0.15 cents per kilowatt hour. There is also a direct tax on nuclear generated electricity that is currently helping to make the government’s deficit smaller. That tax is 0.1 cents per kilowatt hour which provides about $805 million per year.

Lovins also defies logic by describing a system of distributed generators that are not dependent on the grid and then indicates that somehow a diverse, unconnected system is more reliable since the failure of one does not bring the whole system down.

Because 98–99 percent of power failures start in the grid, it’s more reliable to bypass the grid by shifting to efficiently used, diverse, dispersed resources sited at or near the customer. Also, a portfolio of many smaller units is unlikely to fail all at once: its diversity makes it especially reliable even if its individual units are not.

If the portfolio of smaller units is not connected together, their diversity does not provide any reliability since a failure of a generator means the customers of that generator have no power. If I own a building or a factory, I certainly do not want a situation where my entire facility loses power if my generator breaks down – we would be burning up money while waiting for the repairs to be completed.

If a bunch of generators with uncontrollable power outputs are hooked together, they will form a very unstable grid, unless there is a larger group of generators that can provide enough grid stability to overcome the frequently varying power output of systems like wind turbines or solar collectors. (People who live in California or certain areas of the Southwest might think that sunshine is pretty steady, but us east coast people have these things called clouds.) Most engineering studies that I have read indicate that variable sources should make up no more than 20% of a grid and that the closer one gets to that limit the more losses will be incurred to provide reactive power control. (I am pretty sure that not one of Lovins many publications says anything about the need to control power factors in an electrical power system. I am not even sure if he knows what reactive power is.)

Lovins commits a sin of omission by focusing entirely on electrical power generation and ignoring the fact that the world uses energy for a number of other purposes, like moving goods and people from place to place. Nuclear power is a well proven source of ship propulsion power and ships currently burn about 4% of the world’s oil. They produce a much larger portion of some of the more nasty air pollution components like sulfur dioxide and microscopic particles.

He also indicates a complete misunderstanding of the current market for natural gas by making computations in a paper that is supposed to be current using a gas price of $7.70 per million BTU with a modest inflation rate of 5%. According to Bloomberg, the price at yesterday’s close for Henry Hub was $10.70 per million BTU. That price is for May 2, 2008, a time when there is very little heating or cooling demand! Following Lovins micro-power recommendations would put ever growing demands on what is already a limited supply, a situation that is sure to drive prices rapidly higher.

Of course, higher energy prices are a source of enormous profits for many of RMIs customers. I will end this diatribe with one more rendition of Lovins comment about the “risk” of finding a clean, cheap, abundant energy source and a request for you to consider the following questions – who should you trust for policy recommendation when it comes to energy and whose motives and view of the world most closely matches yours?

“It would be little short of disastrous for us to discover a source of clean, cheap, abundant energy because of what we might do with it”