Differing Perspectives on New Nuclear Power Driven Partially By Different Positions in Society

During his appearance on Friday, October 30, 2009, John Rowe told the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee believes that there is no market need to push the development of new nuclear power plants. He also stated that his staff has computed that power from new nuclear power plants can only be competitive in the market under conditions of a $75.00 per ton cost for carbon dioxide. Here is a clip from an exchange with Senator Barbara Boxer, who asked him whether he thought that the nuclear title in the bill was a step in the right direction.

I was not invited to testify, but I have calculated that it is important for the United States and the world to work hard now to build on our existing technical and physical capacity foundations to deploy and operate large numbers of new nuclear power plants within the next decade or two. With attention to excellent project management and sound engineering design, I am sure that those plants can compete with all other alternatives, even without establishing a reasonable price on using our shared atmosphere as a combustion waste dumping ground. Mr. Rowe and I both agree that nuclear fission power is a reliable, proven, economical source of power that produces no greenhouse gases or other polluting emissions.

Our difference in perspective and prescriptions for near future development is driven partially by our different positions in society, our different educational background, and our different professional experience. I am pretty sure which one of us has a more encompassing view of the world, but I could be wrong.

I realize that it is terribly unfashionable to point out class differences when engaging in political discussions in the United States of America, but they can affect world views and decisions even if not explicitly recognized. There is a key difference between John Rowe and me – his total compensation package for 2008 was more than 60 times larger than mine, yet my salary and benefits package puts me into the top 10% of households in the United States. The top earner and decision maker in organization that employs me (the Commander in Chief) has a compensation package that is slightly more than 4 times as large as mine. If John Rowe has ever had to struggle to make a living, that experience for him is many decades in the past. I quite frankly doubt that he even knows anyone who worries about how to make ends meet.

When Mr. Rowe makes recommendations to the Senate for rules affecting the cost of producing and delivering energy, he is making them based on his position of wealth. He is also making them based on his expansive financial interest (check out his unexercised option package) in the performance of a company that is reaping the benefits of operating 17 nuclear power plants that were built in a previous era with other people’s hard work. As most CEO’s will freely admit, their job is to serve the interests of shareholders, not the interests of employees, customers, the common good of the United States of America or the interests of people who inhabit the planet.

Unlike Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Larry Page or Sergey Brin, John Rowe did not make it to a top dog position in the American business community by developing useful products and building a company focused on making those products available to people at a price they were willing to pay. He is a lawyer whose career history more closely resembles that of Samuel Insull. He is not a technically minded man who can recognize improved ways to build a mousetrap.

Rowe has succeeded more by picking up and assembling the choicest slices of already existing enterprises, driving his people hard, and reducing employment. According to Exelon’s annual reports, the company has reduced full time employment from 29,000 in 2001, soon after it was formed through the merger of Unicom with Peco, to 19,600 in 2008. Based on the statement in Rowe’s response to an earlier question from Senator Boxer, Exelon has reduced its headcount to about 17,000 in 2009 even though its profits remain strong. Between 2001 and 2008, its operating revenue has increased from $15 billion to more than $19 billion. Net income has increased from $1.4 billion to $2.7 billion. Those kinds of numbers excite investors, but Exelon has a reputation within the power industry as an exacting employer and as power supplier that makes more money as electricity prices increase.

As is the case for almost any commodity, electricity prices in deregulated wholesale markets are inextricably linked to the balance between supply and demand. If demand increases more rapidly than supply due to something good like a vibrant economy, electricity prices increase. If demand drops due to a recession, factory closings, and customers who carefully monitor their power usage to try to get by on their unemployment checks, the price of electricity drops and the unit sales volume for companies like Exelon also drop. This behavior can lead some to believe that Exelon has motives that are similar to those of the rest of us – it does well when the economy is strong and less well when it is weak.

However, if the supply of electricity increases faster than demand, as it did during the period from 1970-1990 due to the rapid acceptance of a new power source like fission, the electricity suppliers quickly begin to worry about having “excess capacity”. During the first Atomic Age, when electricity suppliers were legally protected monopolies who expected to be able to pass all costs on to customers through rate increases, overcapacity turned out to be expensive for customers who faced rate increases to pay for production facilities that were often idle or underused.

That situation got pretty bad for Commonwealth Edison (one of the components that makes up today’s Exelon) until the customers revolted and pressed their elected officials and public utility regulators to hold hearings on the prudence of the decision to invest in “more capacity than needed”. I am certain that Rowe and his advisors on the Exelon staff have a deep understanding of the 1980s and 1990s overcapacity situation and the opportunity that it offered them to purchase a troubled company with high value assets.

In a truly competitive commodity marketplace – like that which exists for flash memory chips, soda, LCD screens, or corn – when more efficient, less expensive technology becomes available, some suppliers are motivated to invest to build new productive capacity. If that new capacity creates an “oversupply” situation, it pushes out the older, less efficient, more expensive production facilities as prices in the market FALL to a point where the older facilities are no longer profitable to operate. That process can be painful and expensive for the owners of higher marginal cost production capacity, but it is an overall benefit for the economy and for customers who can purchase products that have been made in better, more efficient facilities.

It is far more profitable to be able to operate existing facilities as “cash cows” than to get involved in the technically challenging and financially risky enterprise of building complex new projects and delivering them on time and on budget. That effort requires a completely different skill set than continued excellent operation of existing facilities. As long as the incumbent can discourage anyone else from investing in new capacity, they can enjoy the profits that come from being a dominant supplier of a needed commodity in a market that is perhaps slightly underserved so that prices and margins remain strong. Incumbent suppliers often work hard to increase regulatory and financial “barriers to entry”; that behavior has been practiced by many company leaders in the electricity business for at least 100 years.

During his testimony, Rowe repeated a concept that he has been repeating since at least 2002, when he was interviewed by BusinessWeek for its March 25, 2002 issue. Here is what he said then:

Q: Looking at the rest of the value chain, if you will, one of the strong points of Exelon is its big nuclear fleet. What do you see in the future for nuclear?

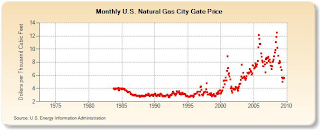

A: It’s my opinion that someday, there’ll be a new generation of nuclear plants, but I don’t believe that day is close at hand because natural gas is very cheap again. And I think that every analysis of the commodity markets suggests that over the next 10 years, natural gas will be cheap many more years than it is expensive. As long as that’s the case, economics drives new plants to be gas-driven.

It is interesting to compare that statement, made in 2002, with the reality of the natural gas market price behavior that occurred between March of 2002 when it rose from $3.84 per million BTU to $12.48 per million BTU in July 2008.

Exelon reported record revenues of $5.3 billion in the third quarter of 2008. At that time energy demand in the United States slumped dramatically due to a deeper recession than anything since the Great Depression. It is a useful exercise to see the effects of continually rising natural gas prices on the revenues, margins and net income for the company that pays Mr. Rowe approximately $9 million dollars per year. Here is what he said on October 30, 2009:

Here is the transcript from the above:

Voinovich: Mr. Rowe. Nuclear. You and I had a talk about nuclear and the feasibility of nuclear coming on to the degree that is anticipated in this bill in 2020 and 2030. What is the possibility of having that number of nuclear power plants? And, last but not least, what do you think of the natural gas title that is in this bill that encourages the use of natural gas?

My feeling is that what it will do is to take the pressure off going forward with nuclear and getting the carbon capture technology that we need for coal.

Rowe: Senator Voinovich. As I said in your office, I believe that the six or eight units that are supported by the existing federal loan guarantee program will go forward and be in operation by 2020. I do not think there will be a significantly larger number than that.

If those units are successful, I believe that there will be more on line by 2030. But as I told you in your office, I doubt that it will be many tens, let alone 100. And, as your question implies, the economics of new nuclear at the present time are haunted by the fact that natural gas is, and appears likely to be for the next decade, at very low prices.

And so the low cost solution for the next decade is often natural gas and that takes, as you say, pressure off to work on either new nuclear or the more advanced forms of renewables that others like.

When Rowe speaks about the need to someday build new nuclear plant capacity and makes it clear that he believes that time is in the distant future, please understand his current position and recognize that he is probably not representing your interests. I do not think there are too many Atomic Insights readers who travel in the same business and social circles as Mr. Rowe does. I know there are very few Americans who do.